Clybourne Park

Written by Bruce Norris

Directed by Amy Morton

at Steppenwolf Theatre, 1650 N. Halsted (map)

thru Nov 6 | tickets: $20-$75 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read entire review

Undeniably, a tragic contemporary masterpiece

Steppenwolf Theatre presents

Clybourne Park

Review by Catey Sullivan

You could reduce Clybourne Park to a trite but true cliché – the more things change, la plus la meme chose. But while Bruce Norris’ evisceratingly powerful (and equally funny) drama does indeed illustrate that depressingly reliable maxim, reducing the piece to an adage would do a grave disservice to both the playwright’s scathing examination of racism and his pull-no-punches, bruising ability to tell a thrashing-good story.

Directed by Amy Morton, Clybourne Park begins in 1959, and sets to ripping the pretty cover from a Father Knows Best exterior to explore the toxically racist turbulence that festers just below the surface. With the second Act, Clybourne Park jumps 50 years to 2009, where it etches a similarly scathing portrait of the vicious hypocrisy boiling just below the façade of neighborly gentility. The endgame conclusion is harsh. We’ve come a long way baby? Perhaps not.

Norris structures his plot around a marvelously creative riff on A Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry’s ground-breaking drama about the first African American family to move into the all-white (fictional) Chicago neighborhood of Clybourne Park. Norris’ first act takes place just before the African American Youngers (never mentioned by name or seen on stage) move in. The second act takes place after they’ve long gone. The sole character who shows up in both Raisin and Clybourne Park is Karl Lindner, head of the Clybourne Park Improvement Assocation. In Raisin in the Sun, Lindner tries to buy the Youngers out, offering them a substantial sum to keep out of the neighborhood. Clybourne Park picks up just after Lindner’s attempt a maintaining “cultural values” fails. Fresh from being turned down by the Youngers, Lindner attempts to circle the white Clybourne Park wagons and find a way to fend off the impending “crisis” of “Negroes” moving into the neighborhood.

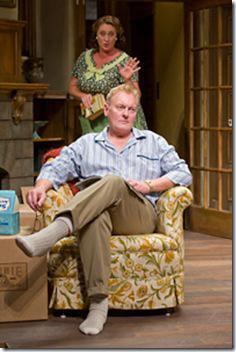

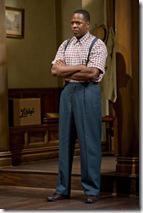

That discussion (which quickly deteriorates into a molten avalanche of soul-searing ugliness) takes place in the home of Bev (Kirsten Fitzgerald) and Russ (John Judd), the white couple that has unwittingly sparked the beginning of neighborhood integration with the sale of their home. Among the deeply concerned citizenry: Lindner (Cliff Chamberlain) and Jim (Brendan Marshall-Rashid) , the pastor from the local church. Among the less offensive (and logically ludicrous) assertions Lindner makes; “Negros are happier when they live in their own communities.” It’s no wonder that his wife Betsy (Stephanie Childers) is deaf. A hearing woman would never be able to tolerate Karl Lindner. The entire discussion (to put it politely) becomes all the more cringe-inducing because it ensues in front of Bev and Tom’s African-American maid Francine (Karen Aldridge) and her husband Albert (James Vincent Meredith).

Norris’ mastery of dialog is supreme. When not making the audience flinch under the full-frontal assault of blatant, oblivious racism, he’s making it laugh at matters that are as tragic as they are humorous. The comedy is as shocking as the casual, KKK-friendly attitudes of the good people of Clybourne Park, with Norris drawing laughter from situations that absolutely aren’t supposed to be funny. In eliciting that laughter, he indicts everybody in the theater. Sure, Karl Lindner would be completely at home marching in a pointed white robe. But what does it say about the audience (about you?) that it finds hilarity in Lindner’s carefully parsed final real estate solutions?

With the second act, Norris shows just how far we haven’t come in 50 years, as yet another group of concerned neighbors gather. This time, the discussion is maintaining the architectural and cultural integrity of a rapidly gentrifying, predominantly African-American neighborhood, a concern voiced with eloquent conviction by Lena (Aldridge) and her husband Kevin (Meredith)

The primary concern is over the new home Lindsey (Childers) and Steve (Chamberlain) are planning to build on the site of the Younger house. That Lindsey and Steve are white has nothing to do with the neighbors’ concern over such teardowns and everything to do with honoring the area’s rich history. Except, of course, despite everyone’s protestations to the contrary, race has everything to do with it.

|

As in the first act, the meeting quickly deteriorates. Neutral issues of frontage and elevation devolve with dizzying speed into a free-for-all of blindingly offensive jokes (Why is a tampon like a white woman?) and verbal paralysis. Never mind actually dealing with issues of race and culture, these people can’t even find the words to articulate their concerns. Norris has them stumbling from euphemism to euphemism, each one more awkward, more clueless and more appallingly funny than the last.

In the end, what’s left on stage is a tableau of profound sorrow, as the ghosts of the past bring an exquisitely elegant and equally sad bit of closure to the narrative. That closure comes at a price: Bev and Dan’s reason for selling their home in the first place is a silent punch in the gut, a situation limned with despair and heartbreak.

As ensembles go, Morton’s cast is as close to perfect as one can get. Judd brings an uncompromising edge to Russ, the angry, suffer-no-fools abruptness that comes from surviving a profound tragedy and realizing life is simply too short for hypocrisy and euphemistic tap dancing. Fitzgerald is both heartbreaking and loathsome as Bev, a tightly-wound, spiritually broken women with a sense of white privilege that runs as deep as the very foundation of her house. Meredith does some of the best work of his solid career as Albert and Kevin, lancing 1959 and 2009 conversations alike with kamikaze zingers. He gets some of the best lines in the production – showstoppers that cut to the quick – and he does them mighty justice. Aldridge is just as memorable, giving both Lena and Francine an unflappable dignity.

Chamberlain’s Lindner is every inch the smarmy racist, decked out in the wholesome, all-American façade that seems as wholesome as the Boy Scouts. He creates a character you love to hate, a man whose combination of ignorance and arrogance could be dangerous if he weren’t also utterly unimaginative. Rashid’s Pastor Jim is also an example of oily, white male entitlement cloaked in a veneer of godly concern, a combination of Mr. Rogers and Fred Phelps. This is the sort of fellow who makes you want to take a shower after he shakes your hand.

Clybourne Park is an example of a powerful new classic built on the foundation of an earlier one. It would be a mistake to think that it rests in the shadow of A Raisin in the Sun – or that it diminishes the earlier work in any way. Clybourne Park stands on its own as a powerful, intriguing, gaspingly funny, and undeniably tragic contemporary masterpiece.

Rating: ★★★★

Steppenwolf Theatre’s Clybourne Park continues through November 6th in their downstairs theatre, 1650 N. Halsted (map), with performances Tuesdays-Fridays at 7:30pm, Saturdays and Sundays at 3pm and 7:30pm. (Sunday evening performances through October 16th only.) Free post-show discussions are offered after every performance. Tickets are $25-$70, and can be purchased by phone (312-335-1650) or online at Steppenwolf.org. (Running time: approximately 2 hours, which includes an intermission)

All photos by Michael Brosilow © 2011

artists

cast

James Vincent Meredith*, Karen Aldridge, Cliff Chamberlain, Stephanie Childers, Kirsten Fitzgerald, John Judd and Brendan Marshall-Rashid

behind the scenes

Amy Morton* (director); Todd Rosenthal (scenic); Nan Cibula-Jenkins (costumes); Pat Collins (lighting); Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen (sound); Michael Brosilow (photos)

* Steppenwolf ensemble member