I have been traveling a lot over the past couple of weeks, plus, had to meet a tough deadline on submitting a proposal for antimicrobial surveillance, making the third edition of this year’s research round up a bit late. Also, I have decided to do it on a Monday-Sunday basis to be able to keep some time over the weekend for this post, so the dates have been adjusted for this round up: January 14- January 24, 2016.

1. WHO Declares Ebola Outbreak Over

This is not “research” as such, but in the past several months, Ebola has had a captive audience in the global village; so, when the WHO declares that all three countries (Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia) are currently at zero Ebola cases – it needs to make the headlines!

However, the big problem is that, we have mopped up after ourselves to clean up the Ebola mess, without having done much to address the issues at the core of the problem. Naturally, the WHO plays it safe by defensively declaring that: Latest Ebola outbreak over in Liberia; West Africa is at zero, but new flare-ups are likely to occur.

EPA/Ahmed Jallanzo via ScienceMag

With almost 29,000 people sick with the disease, and 11,315 deaths reported, this was the largest outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in terms of numbers. In fact, it has triggered a knee-jerk, panic-driven reaction in policymakers and healthcare providers, which may not be in the best interests of fighting the disease… but at least, the neglected diseases with epidemic potential are now getting some attention.

In the long term, we need to look at the big picture, understand how sociocultural mores aid and abet disease spread; and devise self-sustaining policies that work within an empowering environment.

2. WHO Reveals New Case of Ebola in Sierra Leone

Not one day after putting out news that West Africa was at zero Ebola cases, another case was detected in Sierra Leone, according to the WHO. The risk of flare ups was stressed by the WHO in the previous day’s news report of zero case status and the immediate reporting of a case further validated that stand. In fact, this goes a long way to show that we have not done enough to address the systemic weaknesses and the vulnerabilities at the human-animal-environment interface to address the problem of Ebola or any other infectious disease with the potential of explosive spread.

3. Dealing with Homeless Patients: BMJ

The BMJ has, in the past few months, shown more interest to move away from the typical model followed by academic journals and seems to be publishing a lot more articles accessible by the common person. This has led to some rumblings about whether the BMJ is becoming a tabloid!

Anyway, coming back to this post. In this research round up, the third article I point out, again, is not research, but a feature article: Keeping homeless patients off the streets. My research interests includes health problems faced by marginalized population, and, in fact, my MD dissertation was on homeless young men in Delhi, so this article hit home for me. A good read for those who are looking to devise ways to institute a rehab program for homeless patients once they are discharged from healthcare institutions. However, I have some doubts about how adaptable or implementable this can be in the developing world scenario.

4. The NEJM’s Criticism of Homeopathy

Yet another non-research article that drew my attention: Regulating homeopathic products – A century of dilute interest. The discourse on the causal improbability of homeopathy and the homeopath’s defense of their craft usually leads to impassioned, and often, caustic debates. However, this well worded NEJM perspective puts the points squarely, without the usual rhetoric that accompanies the debate.

And how can one not end up reading an article that quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes, that keen observer of science, art and human life:

The most caustic critique was voiced by Oliver Wendell Holmes, who declared homeopathy a “mingled mass of perverse ingenuity, of tinsel erudition, or imbecile credulity, and of artful misrepresentation,” while noting the potential therapeutic effect on patients of “the strong impression made upon their minds by this novel and marvelous method of treatment.”

I guess I should mention a disclaimer here: I am not too enthused by the idea of homeopathy and find its premise rather weak, and am in total agreement with this quote attributed to the NEJM’s erstwhile editors:

For example, lamenting the consumption of enormous quantities of alternative remedies, Journal editors Marcia Angell and Jerome Kassirer noted, “There cannot be two kinds of medicine — conventional and alternative. There is only medicine that has been adequately tested and medicine that has not, medicine that works and medicine that may or may not work.”

5. Eluxadoline as a Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) with Diarrhea

OK! So, finally, a research article!

Eluxadoline is a new opioid with mixed effects (mu and kappa agonist and delta antagonist) and this NEJM article is an industry sponsored, placebo controlled trial to see if it is any good. Statistics reveals mostly positive outcomes, with p values worth salivating over! However, I am less than eager to adopt this new drug because it seems to mostly do what other available anti-diarrheals do, with the notable exception that there is a slight risk of getting pancreatitis.

Yeah. They lost me at pancreatitis!

PS: The NEJM sent out the Eluxadoline article as a Teaching Topic email in the Resident e-bulletin service they provide. However, I still remain skeptical and unless I see it outperform drugs like Loperamide head to head, and with better adverse effect profiles, I would not be too inclined to use it or recommend using it!

6. The Research Parasite Brouhaha

The ICMJE came out with a statement on sharing clinical trial data and this consensus statement was published in several journals, one of them being the NEJM. An accompanying editorial on Data Sharing by Dan Longo and Jeffrey Drazen was also published along side this ICMJE statement (which the NEJM is a signatory of, by the way).

The latter quickly went viral, owing to the stand it took on data sharing, and detractors quickly latched onto a couple of paragraphs:

There is concern among some front-line researchers that the system will be taken over by what some researchers have characterized as “research parasites.”

This issue of the Journal offers a product of data sharing that is exactly the opposite. The new investigators arrived on the scene with their own ideas and worked symbiotically, rather than parasitically, with the investigators holding the data, moving the field forward in a way that neither group could have done on its own.

#researchparasite quickly became a thing on the internet, and unless you have been living under a rock, I must be about two weeks late on writing about this!

7. More Zika Virus Panic

The BMJ covers the Jamaican advisory to postpone becoming pregnant, in what I consider is a preposterous policy response, to the emerging threat of Zika Virus. The article states:

“The Ministry of Health is advising women to delay becoming pregnant for the next six to 12 months,” wrote Horace Dalley, health minister, in a public statement. He urged those who were already pregnant to take extra precautions to avoid being bitten.

Not only do these kinds of policy steps seem extreme, unimplementable abd dodgy to me, I wonder what are the human rights implications of the same. On the surface of it, this is an interesting debate – a double edged sword, if you will. On one side is the basic right to reproduction and safely being able to carry and bear a child – a right that should be ensured by the state, which provides healthcare. On the other hand is the threat of an emerging infectious disease event, for which there was zero preparedness, and at this time, what we can do can only amount to mitigation efforts and limiting the damage. Considering that the countries worst hit by the epidemic (Latin American ones, specially) do not have the most resilient and opulent healthcare systems, it might be the only way to limit long term damage from failing to act in the short term.

8. Workforce Planning: Can Quacks Rescue India’s Healthcare System?

The BMJ covers the study on training quacks, a project being undertaken in West Bengal under the leadership of Dr. Abhijit Chowdhury, professor at IPGMER and SSKM hospital, the state’s premier teaching medical hospital, and a member of West Begal Liver Foundation, in collaboration with Jishnu Das, lead economist of the development research group in the World Bank.

This concept has been received coldly, to put it mildly, by the medical fraternity, and someday, when I have more time, I need to read up on this issue and write a more detailed blog post about it!

9. India and Melioidiosis: Another Impending Crisis?

According to an article in Nature Microbiology, we are sitting atop a time bomb represented by undiagnosed, yet spreading cases of melioidosis. South Asia, which has traditionally been considered to be a problem area for Melioidiosis, suffers from massive under reporting owing to poor laboratory and diagnostic infrastructure. Additionally, B pseudomallei is innately resistant to multiple antimicrobials and may lead to mortality rates as high as 70% in untreated or improperly treated cases. The Nature article contends:

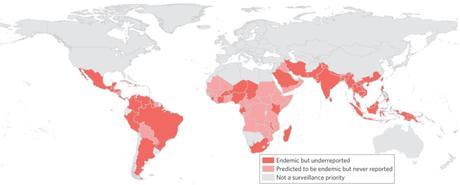

We estimate there to be 165,000 (95% credible interval 68,000–412,000) human melioidosis cases per year worldwide, from which 89,000 (36,000–227,000) people die. Our estimates suggest that melioidosis is severely underreported in the 45 countries in which it is known to be endemic and that melioidosis is probably endemic in a further 34 countries that have never reported the disease. The large numbers of estimated cases and fatalities emphasize that the disease warrants renewed attention from public health officials and policy makers.

Figure 3: Priority countries where microbiological diagnostic facilities and disease reporting systems for melioidosis should be strengthened.

Could this be another crisis in the making?

10. Etymology: Melioidosis

The disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei is known as Melioidosis. It comes from the Greek root, melis, which means “a distemper disease of asses” and -oid, which means like. This is in reference to the disease Glanders, which is a distemper affecting certain animals, and is caused by the agent Burkholderia mallei. The word melioidosis was most likely used in the English speaking medical fraternity first in the 1920s.