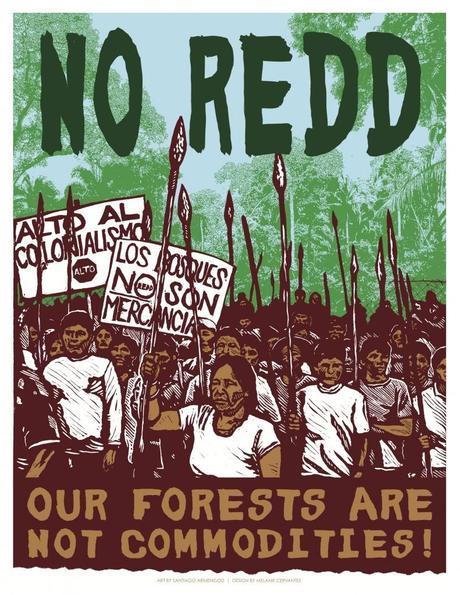

Image: Santiago Armengod and Melanie Cervantes

By Chris Lang / REDD-Monitor

The World Bank continues with its push to trade the carbon stored in forests. But new research shows that safeguards and legal protections for indigenous peoples and local communities in these new forest carbon markets are “non-existent”.

The research was carried out by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) together with the Ateneo School of Government in the Philippines. It includes a survey of 23 countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, covering two-thirds of the Global South’s forests. 21 of these countries are members of the UN-REDD programme and/or the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Brazil has a US$1 billion REDD agreement with Norway. India is the only non-REDD country included in the research.

In a press release, Arvind Khare, RRI’s Executive Director, said,

“As the carbon in living trees becomes another marketable commodity, the deck is loaded against forest peoples, and presents an opening for an unprecedented carbon grab by governments and investors. Every other natural resource investment on the international stage has disenfranchised Indigenous Peoples and local communities, but we were hoping REDD would deliver a different outcome. Their rights to their forests may be few and far between, but their rights to the carbon in the forests are non-existent.”

The report, “Status of Forest Carbon Rights and Implications for Communities, the Carbon Trade, and REDD+ Investments”, can be downloaded here.

The report argues that, “The dispossession of local communities and Indigenous Peoples does not have to be an outcome of the emergence of carbon markets.” But the drive to create markets to trade forest carbon could actually be impeding progress on establishing Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ rights to their land.

Currently REDD country governments legally control vast areas of forest land. Even without forest carbon markets, governments are reluctant to hand over the rights to this land. If carbon markets make forests more valuable, are governments more or less likely to try to hold on to forest land?

RRI and Ateneo School of Government point out in their report that most REDD countries have recognised the importance of land tenure rights. We might therefore expect that in the six years since REDD was launched the area of forest land recognised as owned by Indigenous Peoples and local communities would have increased. The report reviews community tenure in 28 REDD countries and finds that the area of forest land secured for community ownership since 2008 was less than one-fifth of the area in the previous six years:

The report is critical of the World Bank Carbon Fund’s Methodological Framework noting that, it “does not identity or or provide adequate guidance on how to address the risks associated with the existing ambiguity on carbon rights”. The Methodological Framework states, “The status of rights to carbon and relevant lands should be assessed to establish a basis for successful implementation of the emissions reduction program.” But the Methodological Frameworks says nothing about respecting or enforcing those rights.

Of the 23 countries studied in the report, only Mexico and Guatemala have national legislation defining tenure rights over carbon. None of the countries have a national legal framework establishing rules and institutions for trade in forest carbon. Bolivia has passed legislation prohibiting the commodification of ecosystems services.

Six of the countries have draft national laws to establish carbon rights. While 17 countries have legal frameworks that could provide legislation for carbon trading, these laws have not been harmonised, and do not provide safeguards or institutions to arbitrate grievances.

The report points out that,

Even countries that recognize Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ tenure rights over their lands do not necessarily extend this tenure to include ownership of natural resources such as minerals, oil, timber, and other forest products, which can often remain under State ownership. While emissions reductions are not tangible products in the same way as timber or minerals, it is quite possible that governments may perceive them in the same manner, should it suit their interests.

On the other hand, REDD won’t work unless the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are protected. Andy White, RRI’s coordinator, points out that,

Since the birth of the REDD+, organisations have called for secure land rights for indigenous peoples and local communities as a critical component, highlighting the copious amount of research showing that local communities excel at the sustainable management of their land and resources when they are entrusted with greater ownership and control.

Catch 22, then? To work, REDD requires that governments respect the land rights and carbon rights of local communities. But a market for forest carbon could result in large revenues for governments, thus increasing the chances of a “carbon grab” by corporations and governments.