Cross Posted from Los Angeles Times

By Kim Murphy

Out in these windy stretches of cottonwood and prairie grass, not far from where Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer ran into problems at Little Bighorn, a new battle is unfolding over what future energy development in the West will look like.

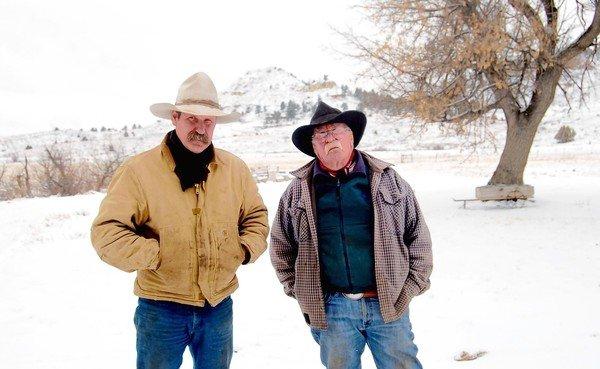

Here, rancher Wallace McRae and his son, Clint, run cattle on 31,000 acres along Rosebud Creek, land their family has patrolled with horses and tamed with fences for 125 years.

They could probably go on undisturbed for 100 years more if the earth under the pastures weren’t laced with coal. A consortium led by BNSF Railway Co. wants to build a rail line to carry some of that coal to market. Nine miles of it would run through the McRae ranch.

The McRaes and some of their neighbors say the Tongue River Railroad, and a proposed coal mine at Otter Creek, puts southeast Montana and ranchers like them at risk for an energy plan that mainly benefits Asia.

“It’s going to cross our land, wreak havoc with our water, go through our towns,” Clint McRae said recently, sitting in the rustic wood house his father built, its hearth hewn from local stone.

The Montana ranchers are in the minority. For many others, coal has been one of the few good things to come out of a region so barren it sent many early homesteaders fleeing to greener lands farther west.

The Powder River Basin in Montana and Wyoming already is producing 42% of the nation’s coal, and with diminishing U.S. markets, producers are mounting a push to serve booming Asian industrial centers. Authorities are reviewing permits for four coal export terminals in Washington and Oregon that would ship up to 150 million tons of coal a year — including coal from Otter Creek — across the Pacific.

The issue has quickly become the hottest environmental debate in the Pacific Northwest. Nearly 9,000 people showed up at recent hearings on the export terminal proposed near Bellingham, Wash. More than 14,000 comments were collected, pitting those hoping for a new U.S. energy bonanza against citizens concerned about coal dust pollution and increased rail traffic.

Since the 1970s, coal has earned Montana $2.6 billion in tax revenues, and the Otter Creek Mine would bring more, along with 2,000 construction jobs and 350 mining jobs.

Those facts count to the McRaes’ non-ranching neighbors in Colstrip, where a 2,094-megawatt power plant burns coal from another nearby mine — and where the Tongue River Railroad would join the existing railroad line.

“Otter Creek is probably the biggest development opportunity our state will see in our lifetime,” said Jim Atchison, director of Southeastern Montana Development, an economic promotion group. “So even though people may be complaining about coal development and how dirty rotten bad it is, it pays a lot of bills in the state of Montana.”

The McRaes contend that the biggest costs are the ones you can’t see — the underwater aquifers that already have been polluted with coal ash.

“We have 16 springs on this ranch, and every single one of them comes out of a coal seam,” said the elder McRae, 78. “Now, they call us radical environmentalists because we want the laws enforced.”

The 42-mile-long Tongue River Railroad, they said, would bring its own problems. Seven trains a day would disrupt their cattle operations and impede efforts to fight rangeland fires

“They will cut off our cattle from water — it’s like a concrete wall,” said Clint McRae, 50. “And if we don’t fence it off, we’re going to have cattle just wiped out by trains.”

The McRaes these days tell neighbors in Colstrip it’s not just the future they need to think about; look what’s already happened to the past. A widely known cowboy poet, the elder McRae penned a verseabout landmarks that disappeared when the coal men came in. “Nobody knows, or nobody cares, about things of intrinsic worth,” he wrote.

Colstrip Mayor Rose Hanser counters that coal helped make southeast Montana a habitable place.

“We probably have two or less people per square mile in this part of the country. So when you’re providing jobs for hundreds of people in a state that has less than a million residents, you are impacting the economy of an entire state,” she said.

There has been some pollution, she said, “but the trade-offs are incredible. You have a better education system, you have better infrastructure, better recreation and activities.”

Lately, the McRaes have found new allies as plans for the coal export terminals raise the prospect of a large number of coal trains running through places such as the Columbia River Gorge and the Seattle waterfront.