Q: In the novel I’m working on, one of the characters is a Puritan whose wife dies during childbirth. I’ve been unable to find any information concerning medical practices in 17th century New England and I’m hoping you might be able to assist. What were the specifics of obstetric practices at that time. Were midwives used? Were husbands present for delivery as they very often are today?

A: In the 1600s there were no hospitals and doctors knew very little. How little? It wasn’t until 1628 that Sir William Harvey (1578-1657) published “De Motu Cordis,” his famous treatise, outlining his discovery that the blood actually circulated through the body. Prior to this, physicians lived under the erroneous assumptions espoused by Aristotle, Galen (approx AD 130-201), and Andres Vesalius (1514-1564). The Germ Theory of infectious diseases wasn’t even a flicker in the minds of scientists. It wasn’t until 1870 that Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch developed this concept. Vaccination as a means of preventing disease was over a century away: Smallpox (Edward Jenner, 1796), Anthrax and Rabies (Pasteur, 1881 and 1882, respectively), Tetanus and Diptheria (Emil von Behring, 1890), and Polio (Jonas Salk, 1952). Antibiotics such as penicillin (Alexander Flemming, 1928) did not exist and surgical anesthesia (Crawford Long, 1842) wasn’t around.

Needless to say, childbirth in the 17th Century was a risky proposition. Mothers often died as did the infant. Most commonly from bleeding and infection, since methods to control bleeding were crude and treatment of infections was non-existent. The problems of breech or other abnormal births led to death more often than not.

At that time, few doctors existed, especially in America, and the population was predominately rural. Most people lived on farms or in very small communities and the large majority of these areas did not have a doctor for miles if at all.

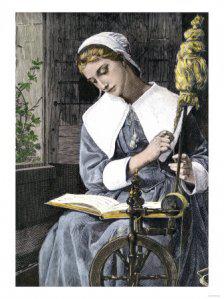

Though trained midwives were common in Europe, there were few if any in America during Puritan times. Thus, deliveries were often performed by a member of the community. Perhaps one of the older women, who became a de facto midwife. She would likely travel by horseback or on foot from farm to farm and attend the births.

The deliveries would take place in the home, usually in the bedroom. If the home was a single room cabin, family and friends would wait outside until the ordeal was over. Hot water, freshly washed cloths, bare hands, and a healthy dose of fear and anxiety were the only available tools. An understanding of post-partum infections (called Puerperal Sepsis) wouldn’t be delineated until Ignaz Simmelweis developed sterile delivery techniques in 1847. If severe bleeding or infection occurred, prayer and comfort were the only salves. And if the infant entered the birth canal in an abnormal fashion, such as a breech (butt first) or footling (foot first) presentation, death of the mother and the infant was likely. Obstetric anesthesia and analgesia consisted of a piece of wood or leather the mother could bite down on. Perhaps in some communities alcohol or tincture of opium would be available. Interestingly, both alcohol and opiates tend to diminish uterine contractions with the net effect of prolonging the mother’s ordeal.

The husband would not likely be present during the delivery. That is a more modern invention. The 1600s were very puritanical. Even a physician wasn’t often allowed to undress a female patient for his examination. If he needed to listen to the patient’s heart or lungs, he would place his ear against the patient’s chest. With a female patient, this was rarely allowed. Thus, Rene Laennec invented the stethoscope (1816) to circumvent this problem.

All in all, childbirth was a dangerous, bloody, and noisy affair. Also immensely rewarding, since the very survival of the community depended upon it.