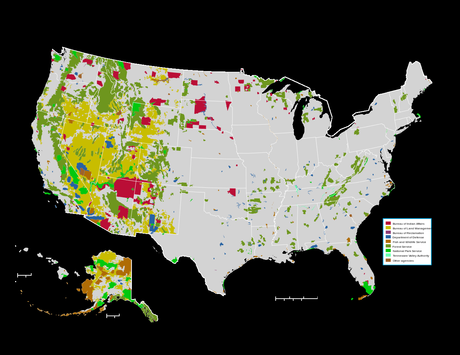

In Wyoming, we’re blessed with public lands. The Federal government holds in trust for us 3.5 million acres – 55,000 square miles – 48% of the state. This is a treasure that too many people take for granted. They should live where land is mostly private – other states, other countries. Then maybe they would appreciate our public lands and the importance of keeping them public.

US Federal lands (including Indian Reservations, which are not public).

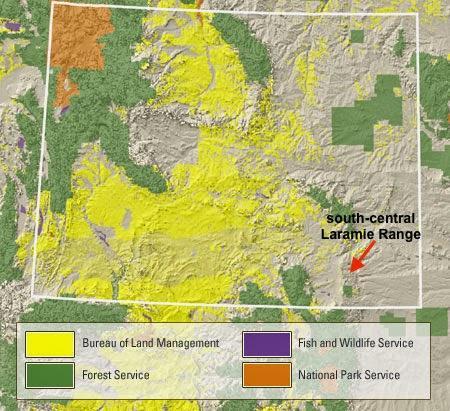

Federal public lands in Wyoming. Note that there are none in the south-central Laramie Range.

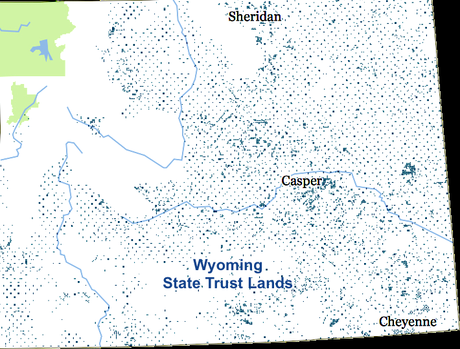

Federal lands are not uniformly distributed. In the eastern part of the state (where I live) much of the land is private. Fortunately there are exceptions. Look closely at an ownership map and you will see scattered blue squares. These are State Trust Lands – one-square-mile opportunities for the public to discover and enjoy natural history in areas otherwise off-limits.

In most Townships (survey units) Sections 16 and 36 are State Trust Lands, hence the regular pattern. (Green areas are National Parks.)

State Trust Lands in Wyoming are public, but there are some restrictions. Most importantly, they’re only accessible if there’s a public way to get there. Do NOT cross private land without permission in order to reach a state section – that’s trespassing! Right of access can be confusing, and conflicts are common. The Office of State Land has released a handy app that clarifies which lands are open and any restrictions that apply.“Access to state lands is very important to the people of the state … These maps help provide information on the front end and hopefully this will limit these sorts of conflicts going forward” – Governor Matt MeadSeveral weeks ago I investigated two State parcels in the south-central Laramie Range, which is mostly privately-owned. The vegetation is dominated by grass and sagebrush. This may explain why ownership is private – early settlers homesteaded the grasslands to raise cattle and sheep.

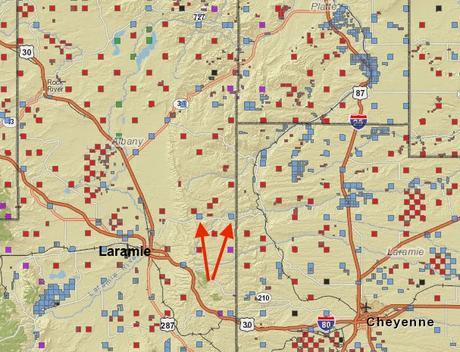

The south-central Laramie Range is largely treeless and mostly privately-owned.

Arrows point to the two State parcels I visited (from the State Lands app).

The two parcels are on the crest of the range along the gravel-and-dirt road from Laramie to Horse Creek. This a land of rock. Outcrops of all sizes dominate the landscape. The area is underlain by a puzzling collection of intrusive igneous rocks called the Laramie Anorthosite Complex. In fact, this part of the Laramie Range “is one of the best places in the world in which to study the origin and evolution of massif anorthosites” (source). But having an anorthosite complex nearby is a two-edged sword, even if it is one of the best. The LAC is fascinating but puzzling … fun to ponder but impossible to explain, beyond intelligent hypotheses.

The area is underlain by a puzzling collection of intrusive igneous rocks called the Laramie Anorthosite Complex. In fact, this part of the Laramie Range “is one of the best places in the world in which to study the origin and evolution of massif anorthosites” (source). But having an anorthosite complex nearby is a two-edged sword, even if it is one of the best. The LAC is fascinating but puzzling … fun to ponder but impossible to explain, beyond intelligent hypotheses. This is a global problem. Many “massif type” anorthosite complexes were emplaced 1.4 to 1.5 billion years ago, but it’s not clear how or why (see Ashwahl 2010, e.g.). The LAC’s complexities and controversies are intimidating, but one of these days I may feel brave enough to put together a post about our geological wonder. [Readers … can you recommend recent literature?]Whatever its geologic story, I like the LAC’s stark landscapes. I’m no petrologist, and I couldn’t be sure I was looking at anorthosite. But that’s what most of the outcrops are in the west parcel, according to the road guide.

I’m no petrologist, and I couldn’t be sure I was looking at anorthosite. But that’s what most of the outcrops are in the west parcel, according to the road guide. Intriguing ribs of reddish rock stretched across the ground in the west parcel (photo below). They might be monzonite as they matched the description in the road guide (fine-grained, dark reddish-brown) … or maybe monzosyenite. In any case, they were beautiful in form and texture.

Intriguing ribs of reddish rock stretched across the ground in the west parcel (photo below). They might be monzonite as they matched the description in the road guide (fine-grained, dark reddish-brown) … or maybe monzosyenite. In any case, they were beautiful in form and texture.

The reddish outcrop is a dike, possibly monzonite.

Lichen on igneous rock.

In the east parcel I found outcrops of Sherman granite, which I know well from Forest Service land to the south. Sherman granite is one of the igneous intrusions of the LAC.

Same area … different granite?

The view east from the east parcel was a geological treat. It includes the east flank of the Laramie Range and the Great Plains beyond. The landforms are familiar to students of Wyoming geomorphology: hogbacks of Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks steeply tilted during uplift, and in the distance a flat-topped ridge of Tertiary sediments deposited after uplift – debris eroded off the young mountains.

Hogbacks on left skyline; relic Tertiary surface on right, in distance.

I drove another mile or so east and stopped at a pull-out to look at the impressive hogbacks. A group of mule deer walking north stopped to look at me. Maybe they were going to visit the privately-owned hogbacks. Lucky deer … they have privileges I don’t.

Mule deer and hogbacks.

--- ✿ ✿ ✿ ✿ ✿ ✿ ✿ ---The plants were a lot easier to "understand" than the rocks. The growing season had barely started so I had to search carefully for wildflowers, but I found more than I expected. It was wonderful to see spring color!

Sagebrush buttercup, Ranunculus glaberrimus, is one of the earliest wildflowers to bloom. Already the petals had fallen off and fruit were maturing.

Rocky Mountain bluebells, Mertensia humilis.

Wyoming kittentails, Synthyris (Besseya) wyomingensis.

The Easter daisies were spectacular in the generally-drab setting. They’re low plants, but showy with their large daisies.

The Easter daisies were spectacular in the generally-drab setting. They’re low plants, but showy with their large daisies.

Easter or Townsend daisy, Townsendia sp.

And who’s this … crouching low in the dead grass?

And who’s this … crouching low in the dead grass? It’s the rock-jasmine, a favorite. Its flowers are so tiny and elegant that they must belong to the Fairies' world. I wish I could find a way in!

It’s the rock-jasmine, a favorite. Its flowers are so tiny and elegant that they must belong to the Fairies' world. I wish I could find a way in!

Western rock-jasmine, Androsace occidentalis.

The next photo probably looks like an out-of-focus shot of small white flowers. But no … I was photographing spikemoss in the foreground. The angled structures are spore-bearing strobili.

Rocky Mountain spikemoss, Selaginella densa. It’s a fern ally, part of a grab bag of not-closely-related, non-fern, spore-producing plants.

The small white flowers behind the spikemoss are Hood’s phlox. It's also called carpet phlox, and there was a time when Wyoming children called it “Mayflower” (source).

Hood's phlox, Phlox hoodii. Gray leaves and dead red stems are a wild buckwheat (Eriogonum sp.).

A few spring beauties were hiding in the grass in the shade of a single ponderosa pine. The tree grows on a granite outcrop surrounded by dry sagebrush grassland. It’s small so its shade is limited, but it’s enough to increase the local diversity a bit.

Spring beauty, Claytonia lanceolata, shows off its pink spring finery.

I suspect this pine (Pinus ponderosa) survives on water that collects in deep rock crevices.

Small saplings are trying to make a go of it too.

Then I heard a meadowlark. He was taking advantage of extra elevation provided by rock and tree to broadcast his song. He moved to the top of the pine, and kept singing while keeping an eye on me and my field assistant.

He moved to the top of the pine, and kept singing while keeping an eye on me and my field assistant.

By late afternoon when I headed home, I had covered only a small portion of these parcels. But I found much of interest – both plants and rocks. And I now have two more natural areas to explore ... two more examples of the value of public lands.

Sources (in addition to links in post)

Ashwahl, LD. 2010. The temporality of anorthosites. Canadian Mineralogist 48:711-728.

Culp, PW, Conradi, DB & Tuell, CC. 2005. Trust lands in the American West: a legal overview and policy assessment. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy & Sonoran Institute. PDF

Frost, BR and colleagues. 1993. The Laramie anorthosite complex and Sherman batholith, in Snoke, AW, Steidtmann, JR, and Roberts, SM, eds. Geology of Wyoming. Wyoming State Geological Survey Memoir 5:118-161.Public Lands Foundation. 2014. America’s public lands: origin, history, future. Public Lands Foundation, Arlington VA. PDF

Snoke, AW 1993. Geologic history of Wyoming within the tectonic framework of the North American Cordillera, in Snoke, AW, Steidtmann, JR, and Roberts, SM, eds. Geology of Wyoming. Wyoming State Geological Survey Memoir 5:2-56.