Content Note: There’s mention in this article of the heated debates around feminism and trans, of societal gender inequalities, and of gender-related bullying in schools. I’m using non-binary and genderqueer interchangeably here to mean genders outside of the male/female binary.

Tensions between trans and feminism rarely seem to be out of the news these days. The so-called TERF wars (where TERF stands for trans-exclusionary radical feminist) smolder on and on, flaring up again every so often, as with the latest spate of articles about Germaine Greer’s inflammatory comments about trans women. The TERF wars fit well into the tired old media trope of feminist infighting, where conflict between feminists tends to be reported far more than, for example, areas of agreement between feminists, key developments in feminist thought, or campaigns about continued societal gender inequality. Unfortunately this kind of reporting seems to be a rather good way of discrediting feminism and keeping people’s eye off the ball of social injustice more broadly.

Over the last couple of weeks attention has turned to non-binary trans with Laurie Penny’s article on being a genderqueer feminist and Suzanne Moore’s response. This is interesting/challenging timing for me as I agreed to speak to my feminist reading group at work about non-binary gender this week. I had already been wondering what wider debates were likely to be swirling around us as we had our discussion, and how I could articulate my own thoughts clearly through all of that. I decided – as I often do – that blogging about it first might help me to figure out what I wanted to say.

What’s at stake here?

Reading Laurie Penny and Suzanne Moore’s articles helps to get to the heart of some of the deep feeling that’s in play in these discussions. This can aid us in understanding why they become so fraught, and why there can be such a temptation to polarise into ‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, ‘them’ and ‘us’ – mapping those onto other perceived divisions (e.g. older and younger, authentic and inauthentic, natural and unnatural, etc.)

As I’ve said before, I think it’s useful to recognize the ways in which these kinds of tensions echo and reverberate up and down our multiple levels of experience: in our wider culture, in our communities and organisations, in our interpersonal relationships, and in our internal conversations. I’m struck by the looming, potentially explosive, cloud of emotion which seemed to be present as I read the social media responses to these two articles, and which has also been there each time I’ve been at a feminist event where these kinds of tensions have played out in person. I feel the same roiling, sparking thunderhead settling over one-on-one conversations when these issues come up. Also – like Laurie and Suzanne I suspect – I feel it inside myself as I try to make sense of my own experience of these matters, and to articulate it. This fact was underlined for me by the fact that I just spent 30 minutes staring at my computer screen wondering how to begin the next paragraph!

I think that one of the main things at stake here is the concern that non-binary people – particularly those who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) – are somehow betraying women and/or feminism in their rejection of the category of woman. Laurie explicitly addresses this in their own retaining of the political identity of woman, in additional to her identity as genderqueer (whilst acknowledging that any genderqueer folks who don’t do this are equally legitimate). Jack Monroe – who also recently came out as non-binary – reports that they have been called a ‘traitor to women’. Suzanne hints at the sense of betrayal with her concerns over young ‘sexual tourists’ adopting ‘pick and mix’ and ‘hall of mirrors’ identities. She questions why AFAB genderqueer people could not use identity terms that retain their womanhood (e.g. butch dyke) or recognize that no women feel ‘at one’ with all of what being a woman entails (physically and socially).

In conversations with feminist friends I’ve certainly heard such anxieties expressed: The sense that we should be about expanding the category of womanhood so that anything is possible within it, rather than grasping for a different gender identity if we find that we don’t feel stereotypically feminine. Perhaps there’s a worry that by embracing genderqueer or non-binary labels we’re actually supporting gender stereotypes; reinforcing the idea that the only way to be a woman is to conform to rigid social norms. Or maybe there’s a concern that by moving away from the category of woman we’re somehow suggesting that those who remain within that category are fine with all the restrictions that go along with it. One colleague of mine suggested that some feminists may see gender transitions as individual answers to social problems, leaving them thinking ‘you’ve solved it for yourself, but what about the rest of us?’

It’s so tempting when faced with these kinds of arguments to go on the defensive. My own sense is that most – if not all – of us have arrived at the position we’re in regarding our gender by a painful and difficult path. In these debates there’s often the suggestion that our hard-fought battles were actually much easier and less painful than those of others. Feminists like Suzanne suggest that young queers have it so much better than feminists and queers did in the past – which certainly involves some ignorance of the evidence on non-binary trans experience. But some feminists may well be responding – themselves – to an implicit or explicit suggestion that they are taking an easy path by remaining within – rather than challenging – the gender binary with their own identity and expression. For others, a great pain of regret accompanies seeing the options that are – very gradually – becoming available which simply weren’t there when they were going through their own hardest times. Another colleague of mine pointed out that people can feel very unsettled when somebody shifts who they had previously seen as mirroring their own – stigmatised – identity: the representation of themselves that they had seen in that other person has changed, and that can leave them questioning themselves in uncomfortable ways. In fact there are probably many many different reasons why any individual would find this stuff to be threatening and painful.

It seems to me that it’s vital in these kinds of discussions to listen to one another, and to try to understand the underlying – extremely personal – pain, fear, and rage that is in play. It’s also important to recognize how extremely hard it is to do this when you are feeling that both your deeply-held political views, and your very sense of self, are under attack. There’s something key – for me – about exploring how we can learn to hold all our various experiences and expressions of gender without that sense of being under threat because somebody else is doing it differently. This is not some call to all ‘play nice’ and ignore the very real and raw anxiety and loss that these issues can bring up. Rather it’s a call to keep doing the messy, difficult, painful work of being with each other in all of our difference: seeing each other as whole human beings despite our desire to objectify and dismiss those we feel hurt by into ‘them’ as opposed to ‘us’ (and yes I think the same applies to other areas of gender tension as much as it does to this one).

So – in the hope of such a conversation – here’s my take on the political and the personal of being non-binary and feminist.

The political: Non-binary as feminist

Starting with the political it seems to me that (most) feminism is about challenging the notion that men and women are meaningful categories of difference which legitimise women being regarded as inferior to men and therefore treated less well (being paid less, being more subject to sexual violence, being valued differently, etc. on account of their gender). Intersectional feminismis about challenging the notion that there are any categories into which people can be divided which justify one group being treated less well than another. Intersectional feminism is also about recognising that we need to challenge all axes of oppression rather than just one of them because they cannot be disentangled. If we remove one whilst leaving the others intact then – as Flavia Dzodan so nicely put it – that is not feminism, it is bullshit!

There are two aspects to the underlying societal assumption that feminism is trying to challenge: the bit about the problem with treating one group of people as inferior, and the bit about dividing people into two categories in the first place. It seems to me that it is part of the same battle to point out and try to change gender oppression, and to point out and try to change the assumption that gender is binary.

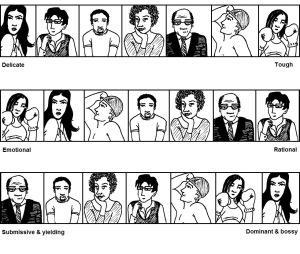

Gender isn’t binary. On any possible biological, psychological or social measure of sex and/or gender it isn’t possible to divide people simply into male or female. Also there have been many times and places in which there has been only one gender, or more than two genders. In western culture at the moment – and for some time now – there has been a lot of pressure to binarise and to keep people in fixed categories of men and women with restrictive norms about what counts within each category. This has an adverse impact on pretty much everybody concerned: on those who struggle to fit those norms, and on those who manage it but then experience immense pressure to remain within the tight confines it imposes. So I think it is important politically to expand what is possible within each of these categories, to question the importance that is placed upon these particular categories, and to point out the arbitrariness of the categories themselves.

The political – and feminist – aspect of being non-binary for me is about continually pointing out that gender isn’t binary: that man and woman aren’t the only categories that people can fit within. That a continuum is a better way of understanding it, and that even that is an over-simplification because we would need multiple continua to conceptualise all of what is understood by ‘masculinity’ or ‘femininity’. Like Sandra Bem I’m hopeful that the proliferation of gender categories might be a way to break the rigid gender norms that currently hurt so many people in so many different ways.

I also feel that non-binary thinking has a great deal to offer beyond gender – for example when we apply it to our tendencies to divide people in categories along other axes of oppression, and when we think about our wider tendencies towards polarised thinking.

The personal: Also political

As the feminist slogan puts it: the personal is political. It isn’t possible to separate out those elements. I feel strongly politically about these matters because of my personal experiences, and it’s important for me to ‘walk the walk’ personally because of my political convictions.

What I know personally is that, for me, the gender binary never felt right. The age at which it started to be imposed rigidly was the age in which I started to learn that I was not okay. I learnt that I couldn’t be part of the group where people were into the same things as me. I learnt that even if I could’ve made a case for joining that group I would have failed (not fitting the ideals of masculinity anywhere near well enough to transgress in that way). And I learnt that trying to join the only available group to me would equally be a fairly constant experience of failure and ridicule until I mastered the performance that would continue to feel restrictive and damaging for decades until I allowed myself to let it go.

I also know that this non-binary place does feel right for me. It’s hard – if not impossible – to articulate the sense of okay-ness that has come with adopting a name that feels like a better fit and a pronoun that I feel comfortable with. Each step towards the physical changes I’m making has come with a wave of kindness towards myself that I simply haven’t experienced in my life before. There’s a sense of giving something back to a person who had so much taken away. There’s a gradual lifting of the self-criticism and self-policing that has dominated so much of my life. It’s not everyone’s path, and – of course – even other non-binary people will have very different paths to mine, but it feels like a path I need to allow myself to follow.

It seems important to me now to work towards a world in which no-one has to go through that kind of bruising and battering gender struggle as a kid, or at any age: Where it’s fine to be whoever you are, to enjoy whatever you enjoy, and to hang out with whoever you hang out with regardless of whether that conforms to the gender stereotypes or opposes them or a bit of both; where it’s fine to be someone who was assigned female at birth but is a boy, or someone who was assigned as male at birth but is a girl, and where it is equally fine for anyone to occupy any of the positions between or beyond those binaries; where all of those things can be be permanent, or temporary, or a bit of both, and not seen as any better or worse for it.

Two things particularly helped me to reach the point in my own life where I’m capable of understanding gender in this way, and of working – through my activism, writing and therapy – to change things. One of them was feminism, and the other one of them was non-binary gender.

Find out more:

- Download ournon-binary gender factsheet.

- Support Gendered Intelligence in their campaign against gender-related bullying.

Here are links to:

- Beyond the Binary (online non-binary magazine)

- Trans media watch guidelines on non-binary gender

- Everyday Feminism on Non-Binary

- CN Lester’s blog

- A talk I did a couple of years back on youtube

- Jay Stewart’s TED talk

- Julia Serano on the problems with much writing around these issues

I’ve written more about non-binary approaches to gender in the chapters on this topic in Rewriting the Rules, Sexuality & Gender, and the Handbook of the Psychology of Sexuality and Genderand there will be plenty more in the books coming out next year on Non-Binary Genders, and on Queer.