by Javier Sethness Castro / Counterpunch

As many readers of CounterPunch are likely aware, the Chiapas-based Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) has recently launched an open initiative called the Escuelita (“little school”), a four or five-day program by means of which outsiders, both Mexican and international, are invited to reside with Zapatistas to learn more about the EZLN’s politics and the daily lives of the organization’s members, as well as to promote cultural exchange. The openness reflected in the launch of the Escuelita stands in contrast to the relative aloofness of the organization in recent years—with the EZLN’s command observing a period of silence for more than a year after Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos’ plaintive condemnation of the Israeli military assault on Gaza during winter 2008-9. Of course, at the end of the thirteenth Baktun and the beginning of the fourteenth (21 December 2012), up to fifty thousand Zapatistas silently marched through five of the municipalities the EZLN had liberated in its 1 January 1994 insurrection—thus overthrowing their prior reclusiveness while dialectically preserving their verbal quietude.

Indeed, in this sense the Escuelita’s founding recalls the early years that followed the EZLN’s public appearance with its uprising, when the organization hosted Intercontinental Encounters for Humanity and against Neo-Liberalism—and even Intergalactic ones—that brought together radical thinkers and dissidents from Mexico and the world over to publicly strategize on ways to bring down capital and the State. I was greatly pleased, then, when in response to a form I had sent the EZLN some time ago, I received a letter signed by Marcos and fellow Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés inviting me to the second round of the First Level of the Zapatista Escuelita, to be held in late December 2013.

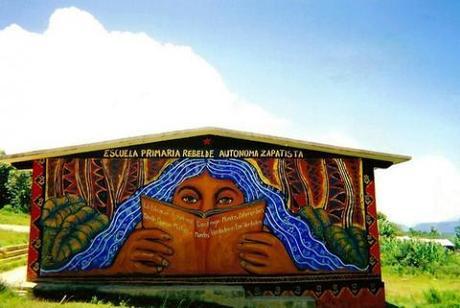

Registration for the Escuelita took place at CIDECI, or the Indigenous Center for Comprehensive Training, which has its campus on the outskirts of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, the largest highland city in the state of Chiapas. Also known as Unitierra (Earth University), CIDECI hosts weekly international seminars on anti-systemic movements, in addition to monthly seminars dedicated to contemplation and discussion of the thought of Immanuel Wallerstein. Much of the art adorning the buildings on the CIDECI campus depicts Zapatistas, and the Center has hosted Sups Marcos and Moisés to speak on several occasions, so it is natural that it would be chosen as site of registration for the Escuelita.

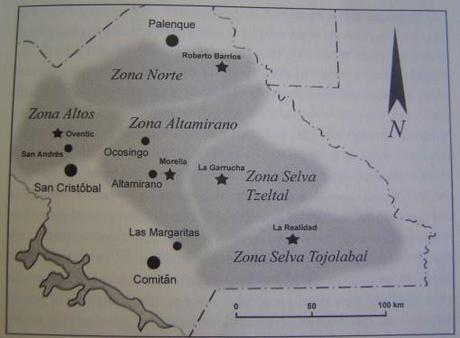

Arriving with my friend Reyna, we entered the short registration line established for foreigners—the lines for those hailing from Mexico City and the states of Mexico being much longer than this one—presented our documents to the receiving team, paid the 380-peso fee (about $30US), and then were told we would be placed in a community belonging to the La Realidad (“Reality”) region located deep in the Lacandon Jungle. I was pleased to hear this, as La Realidad is my favorite of the five Zapatista caracoles (“snails”), or administrative centers located in the zones with Zapatista presence. Reyna and I then got in line to board the various vehicles the EZLN had organized outside CIDECI to transport us to our respective caracoles.

Map of the 5 Zapatista caracoles and their corresponding regions. From Niels Barmeyer, Developing Zapatista Autonomy (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 2009), xvii.

When the caravan from CIDECI entered the jungle and arrived at La Realidad some ten hours after having departed, we were asked to remain in the vehicles outside the caracol compound for just a few more minutes. Thus were we faced with a white banner draped above the iron gate that served as entrance commemorating 20 years since the Zapatista uprising in general and the caída (“fall”) of Subcomandante Insurgente Pedro during the fighting in Las Margaritas in particular. Once the Zapatistas had finished preparing themselves, the alumn@s were invited to file through to enter the caracol, just as skilled masked players struck joyful tunes on the marimba from the stage above where the students came to join the assembled Zapatistas for a brief orientation to the Escuelita.

After declaring our support to the cause of revolution—responding with ¡Viva! to the mention of various persons and groups, such as the EZLN, Subcomandante Marcos, Comandanta Ramona, the Escuelita, the peoples of the world, the world’s women, and so on.—we were assigned to our guardian@s individually and then sent to sleep as segregated by sex while the marimba continued to play into the night. My guardián was a young Tojolabal male BAEZLN (base de apoyo, or “support base”) named Héctor—his name here is a pseudonym for reasons of clandestinity.

Banner in La Realidad Commemorating Sup Pedro, Who Died in the Insurrection on 1 January 1994.

The next morning, 25 December, the Escuelita at La Realidad officially commenced with a collective presentation made by Zapatista teachers of the region regarding different aspects of life and politics in the BAEZLN communities pertaining to this caracol. In basic terms, these teachers spoke to the EZLN’s autonomous health and banking systems—with the former comprised of health promoters, male and female, who are trained in the three fields of acute care, obstetrics, and herbalism, and the latter comprised of lending institutions (BANPAZ and BANAMAS) which offer loans for productive projects at 2-3% interest and provide economic support for Zapatista families struck by illness—as well as their democratic system of governance, which in parallel to the official system is made up of three tiers: the local popular assemblies at the communal level, the autonomous Zapatista rebel municipalities (MAREZ) at the intermediary level, and finally the Good-Government Councils (Juntas de Buen Gobierno, or JBGs), which coordinate matters at the regional level. Of the three, the JBGs represent the highest authority for the Zapatistas, yet legal proposals can be raised at the local assembly level, and the BAEZLN representatives voted into the JBGs through assemblies are fully recallable. The autonomous authorities, moreover, receive no wage or salary for their work but are instead supported with food from their base communities.

While the Zapatistas’ methods in civic administration thus seem to bear a great deal of similarity to the positive policy proposals made in Euro-U.S. settings by Karl Marx and some anarchists alike, they resemble and develop the political customs of many indigenous peoples of the Americas as well. Indeed, in philosophical terms in this sense, one of the teachers expressed the idea—as recognized also by G.W.F. Hegel and others—that the perpetuation of oppressive social conditions drives forward the dialectic: he spoke specifically of the memory of the Zapatistas’ ancestors enslaved by the feudalism imposed by the colonia as propelling the strength of the movement of BAEZLN’toward autonomy. At this time, one of the teachers noted that the EZLN’s goal at present is two-fold: one, to “liberate the people of Mexico,” and secondly to uphold and extend the autonomy of the organization and its constituent members.

The situation of women in the EZLN was first examined an hour and a half into the teachers’ presentation, when various female representatives spoke to the issue. Like Friedrich Engels on private property, the introductory speaker argued that the patriarchal enslavement of indigenous women began with Spanish colonialism, whereas previously the worth of women had supposedly been fully recognized, as based on women’s ability to reproduce the human race. This speaker noted both males and females to have been oppressed by the patrones imposed by European invasion and genocide, and she welcomed the vast changes provided by the EZLN in terms of women’s ability to participate in socio-political matters, whether as health promoters, communal radio progammers, JBG authorities, or milicianas in the guerrilla movement.

Several of the speakers on women’s issues stressed that the struggle to increase women’s participation in the EZLN has not been an easy one, due both to resistance from men as well as the internalization of self-deprecating values on the part of many indigenous women themselves. Another issue is that females in this context tend to be less literate and knowledgeable of Spanish than males, such that engaging in administrative work using Spanish as the common language among BAEZLN from different ethno-linguistic groups proves challenging.

One teacher noted that Zapatista women face exploitation on three fronts—for being female, indigenous, and poor—and based on her and other compañeras’ words, it seems they largely bear responsibility for domestic affairs and child-rearing within the dominant sexual division of labor which prevails in Zapatista communities. Speakers in this section also analyzed the Revolutionary Law on Women, passed by the EZLN before its January 1994 insurrection, by enumerating its stipulations—such as the right to freely determine the total number of children to bear, to reject imposed marriage and freely choose partners, to resist domestic violence, and so on—and afterward simply stating that all the conditions of the Law are being observed in Zapatista settings. However, this claim came too quickly, as we will shall see.

In the third part of the initial presentation in La Realidad, the teachers addressed some of the challenges the EZLN has faced in the development of its autonomy in the 20 years since its armed revolt. They claim now that their form of resistance is the word, both spoken and written: while in January 1994 their resistance took on armed form, it has now become peaceful and civic—with the resort to arms opening the subsequent possibility for the Zapatistas’ impressive development of autonomy.

Despite this difference between January 1994 and everything after, the Zapatista movement remains under siege, with the “bad government” (el mal gobierno) working now to divide indigenous communities among themselves by encouraging participation in official political parties and recourse to state-provided services—a strategy it adopted in direct response to the insurrection, yet one that was subordinated in the years of peak intensity (the years following 1994) to the overtly repressive resort to direct militarization and the fomenting of paramilitary groups designed to terrorize BAEZLN and Zapatista sympathizers in eastern Chiapas.

However, forced displacement of BAEZLN still takes place—consider the cases of San Marcos Avilés in 2010 and Comandante Abel more recently. One speaker mentioned the Lacandon indigenous people who live quite close to La Realidad as an example the Zapatistas do not wish to emulate—for the Lacandones have been made dependent on the State after having been stripped of their rights to fell trees and cultivate agriculture for residing in the region which has been designated as belonging to the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve (RIBMA). Defining the principal problems which the EZLN confronts at the moment, one representative noted the issues of the occupation of lands “recovered” by the Zapatistas in 1994 by indigenous persons belonging to rival political groups, forced displacement, paramilitary activity, and the arbitrary incarceration of BAEZLN. This speaker connecting the experience of these problems with the “peaceful and civil” Zapatista approach, which is to engage in public denunciation through the JBGs.

To close this introductory presentation, the teachers accepted written questions from the audience of alumn@s. In response to a question that would continually be raised over the course of the Escuelita, one teacher said that the Zapatistas “respect” the ways of gays, but no more specifics were given on this. As for the question as to how to reproduce the neo-Zapatista model in other contexts—particularly in cities, where living conditions are clearly rather different—the teachers said that that prospect could be helped along by means of the promotion of an autonomous sense of politics, however that be translated into reality. Intruigingly fielding a question about Zapatismo and ecology, one of the teachers noted that the EZLN seeks to carry through the word of the people in terms of how to manage natural resources, such that the question of whether nature be ravaged or left alone is secondary to adherence to the vox populi—an interesting permutation of “green” anarcho-syndicalism or ecological self-management.

Another question-and-answer had a maestro clarifying that BAEZLN practice a “high level” of abstention in official elections at the three levels (municipal, state, and federal). Perhaps most controversially of all, some of the teachers shared the general neo-Zapatista skepticism toward family planning methods, which are apparently considered in the main to be measures imposed from above to limit indigenous population growth. Along these lines, one maestra clarified that abortion is not performed at Zapatista autonomous clinics, considering it a practice of infanticide that should be suppressed if there are to be numerically more zapatistas. Separately, though relatedly, a different teacher declared that the Zapatista midwives are not trained by the Public Health Ministry.

Following the morning presentation, the alumn@s and their guardian@s traveled by group to the communities in which they would experience the Escuelita. Transport of these 500 people (about 250 students and their chaperones) took place by means of large sand-trucks—traveling in one of these during the journey out to community and back truly reminded me of pictures I’ve seen of the anarchist troop-transport vehicles used in the Spanish Revolution of the 1930′s. Upon arrival to the — community affiliated with the — MAREZ pertaining to La Realidad to which the group in which I was included had been sent, the first session of the Escuelita began for me, as Héctor and I were welcomed into the abode of the — family. (Thus, like many others, Héctor and I experienced the Escuelita with one family, though some alumn@s and guardian@s apparently experienced a more collective setting, such as took place in the actual space of an autonomous school.) The first text to be examined was Autonomous Government I, which like the remaining three volumes of written materials provided for alumn@s and guardian@s to study is comprised of varied testimonies from BAEZLN with different charges who belong to MAREZ affiliated with each of the five caracol regions.

A Scene from the — Community, Affiliated with the La Realidad Caracol

This first volume tells its readers that the EZLN base is comprised of a total of 38 MAREZ, with 4 belonging to La Realidad, and it notes that this caracol was the successor to the first Aguascalientes established in 1994 by the EZLN in the nearby community of Guadalupe Tepeyac—Aguascalientes referring to the Mexican state in which the 1917 Constitution was drafted—which was in turn occupied by the Mexican Army in 1995, its residents displaced for six years until 2001. In 1995, the EZLN responded by founding five more Aguascalientes, administrative centers which would in 2003 become the caracoles and the seats of the JBGs.

In terms of La Realidad, the region itself has an autonomous Zapatista hospital in San José del Rio—with a large state-based one recently installed in Guadalupe Tepeyac, and a government clinic (physically protected by barbed wire) constructed within the last three years just a couple minutes’ walk from the caracol itself. The text on autonomous governance says that the San José hospital has recently acquired ultrasound equipment for obstetrical purposes, but it remains unclear to me to what extent there exist rehab or harm-reduction programs for Zapatistas in public health terms—consumption of alcohol and all other drugs is forbidden for BAEZLN.

Moreover, in sharing the names of all the Zapatista MAREZ which exist, the volume speaks to the role of revolutionary memory in the EZLN’s program: municipalities are named for Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, San Manuel (Manuel being the founder of the EZLN), Ricardo Flores Magón (a renowned Oaxacan anarchist involved in the Mexican Revolution), Comandanta Ramona, Lucio Cabanas (a left-wing guerrillero who formed the Party of the Poor in Guerrero in the 1970′s), La Paz, La Dignidad, 17 November (date of the arrival of the urban-based Maoists to the selva Lacandona in 1983), Trabajo (“Work”), and Rubén Jaramillo (a campesino insurrectionary who sought to carry on Zapata’s vision until his 1962 murder by the State), to give just a few examples. Politically, volume I lists the seven principles of mandar obedeciendo (“to command by obeying”) which is to govern the action of representatives of the JBGs and all other civilian Zapatista institutions:

“To serve and not to serve oneself”; “to represent and not to supplant [or usurp]”; “to construct and not to destroy”; “to obey and not to command”; “to propose and not to impose”; “to convince and not to conquer”; “to go down instead of up.”

Beyond this, the interviews in the text discuss problems with rival organizations in the region corresponding to Morelia such as ORCAO and OPPDIC, and it provides some history showing the necessity of direct JBG oversight of projects proposed by internationals and NGOs to be implemented in Zapatista communities. Moreover, with regard to the northern region affiliated with the Roberto Barrios caracol, the text specifies that economic donations from visitors often go toward expanding cattle-herds, in accordance with the wishes of base communities.

The second volume, Autonomous Government II, which Héctor, my teacher, and I examined on the Escuelita’s second day, gives details about the specific autonomous social projects implemented by the EZLN, especially health and education. Interviews with educational promoters specify the types of classes on offer at the ESRAZ (Escuela Secundaria Rebelde Autónoma Zapatista, or the Zapatista Rebellious Autonomous High School): languages (Spanish and indigenous), history, math, “life and environment,” and integration (on the EZLN’s 13 demands). In the La Realidad region at least, autonomous education programs are designed in consultation with students’ parents, who are asked what it is that should be preserved from standard public education approaches, and what should be added. With regard to autonomous health, the text specifies that EZLN health promoters have composed a list of 47 points for preventative health, that medical doctors assist in solidarity with health projects, and that the San José del Rio hospital had recently acquired an autoclave thanks to revenue from the 10% tax the JBG collects on all construction projects undertaken by community, corporation, or State in its territory.

In the northern zone of Chiapas, vaccines arrive every three months for Zapatista children, and the organization SADEC (Salud y Desarrollo Comunitario, or Communal Health and Development) assists with their administration; my teacher assured me that vaccines are regularly given to BAEZLN children in the zone of La Realidad as well. Furthermore, the second volume mentions various difficulties and successes experienced by the EZLN, both internally and externally: for example, the forced displacement prosecuted by federal forces of the Zapatista San Manuel community located in Montes Azules and the scarcity of land limiting the scope of collective projects to be taken in the highlands region corresponding to the Oventik caracol, or the exportation of Zapatista coffee to Italy, Greece, France, and Germany.

Zapatista School in the — Community with Anarcho-Ayndicalist Colors (Rojinegro)

This same day, my guardián, teacher, and I decided to begin study of volume three, Autonomous Resistance, as well. This collection of interviews provides great insight into neo-Zapatista culture and resistance, as well as relationships between BAEZLN and members of other organizations, particularly officialist grupos de choque (“shock groups”). Providing an interesting perspective on Zapatista child-rearing practices, one representative explained the various alternative cultural activities Zapatista communities offer to their youth so that they not fall into “ideologies of the government”: sports, poetry contests, and dance. Also in terms of cultural norms, another interviewed spokesperson notes the celebration of religious holidays to be more popular outside the ranks of the EZLN than inside it—a reflection of the organization’s secular orientation. A socio-cultural milestone for the EZLN, the first and only appearance of the neo-Zapatista air force is also described in this volume: to protest the military’s occupation in 1999 of Amador Hernández, a La Realidad MAREZ, local BAEZLN organized a mass-production of paper airplanes carrying subversive messages which were ceremoniously launched into the barracks of the soldiers upholding the occupation. The resistance to this occupation also took on the form of sit-ins, dance, and exhortative speech.

In addition, the third volume examines Zapatista diplomacy and relations with other organizations. The construction of water-irrigation projects with which many internationals involved themselves—as is described in Ramor Ryan’s Zapatista Spring: Anatomy of a Rebel Water Project (2011)—is mentioned as a sign of international cooperation and solidarity, while in contrast relations with local communities affiliated with the PRI (the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party) and ORCAO/OPPDIC (comprised in part by ex-BAEZLN) are shown to continue to be tense and problematic.

Indeed, it seems there is a true political competition going on between BAEZLN on the one hand and PRI militants on the other, with a number of respondents from the Morelia and La Garrucha regions expressing faith and pride that BAEZLN in many cases live better than their PRI counterparts, thanks to the organization’s reportedly consistent besting of the official system in health and educational outcomes—this despite the myriad social programs offered by the Chiapas state government, and the millions of pesos it spends on them. In universal (or galactical) terms, an education promoter from the Roberto Barrios region tells his interviewer that the neo-Zapatista struggle proceeds not only with the interests of BAEZLN in mind, but of all—tod@s.

The reading for the the third day was the fourth volume, Women’s Participation in Autonomous Government, perhaps the most interesting one of all—for it is testament to the patent conflict between Zapatista rhetoric and everyday life in this regard. From the La Realidad region, an ex-JBG member notes proudly that in neither organized religion nor in established political parties have women experienced the kind of participation that female BAEZLN have been allowed. A member from an autonomous council of the same zone claims the lot of Zapatista women to be better off than that of indigenous women in PRI communities, where high rates of alcohol and other drug abuse and sexual violence reportedly obtain.

Nonetheless, a great deal of tension between the end of women’s liberation and respect for established patriarchal custom can be readily detected in this volume on women’s involvement. For example, the 47 points on preventative health from La Realidad include one endorsing family planning, while health promoters affiliated with Morelia suggest to their female clients that they ideally try to leave a 5- or 6-year gap between each subsequent birth, all in accordance with article 3 of the Revolutionary Law on Women, which grants female BAEZLN the right to elect the number of children they will bear—yet sources from Oventik and Roberto Barrios note that it is precisely this law no. 3 which is being least observed in practice, given the strong opposition expressed by many male BAEZLN to the use of birth control methods.

Indeed, summarizing the results of a public discussion among BAEZLN in the Roberto Barrios region on women’s issues, one educational promoter reported the widespread opinion that women should not unilaterally decide on the question of number of children—thus expressing a popular repudiation of law no. 3! From La Garrucha, another educational promoter claims that women’s participation in her MAREZ is 2-3% of what it should be—that is, if I’m not mistaken, that >97% of female Zapatistas from that municipality opt out of taking on the charges passed to them through election. Sexual education would seem underdeveloped in the Roberto Barrios region, according to a Zapatista educator there, and in this zone marriage is common by 15 or 16 years of age, while in the Oventik region unmarried couples are apparently expected to ask permission from their parents to date—so that they avoid the “bad customs of the cities where lovers just get together without respecting their parents.”

In these terms, an interesting proposal from the base is that of the recommendations made in the Oventik zone in 1996 for an expanded Revolutionary Law on Women—a proposal that has yet to be adopted by the EZLN. While from volume IV it is unclear how this proposed expansion came about, and who precisely composed its articles, it in some ways reflects regression from the original Revolutionary Law: here, it is only married women who have the right to birth control, and this only to the extent to which agreement with male partners is achieved, while non-monogamous relationships are declared unacceptable: “it is prohibited and inappropriate that some member of the [Zapatista] community engage in romantic relations outside of the norms of the community and populace—that is to say, men and women are not allowed to have [sexual] relations if they are not married, because this brings as consequences the destruction of the family and a bad example before society.” In a similar vein, “arbitrary abandonment” and coupling with others while formally married are also tabooed in the articles of this recommended expansion. Whether such attitudes are representative of the thought of many or most female BAEZLN is unknown; however conservative such ideas may seem, it is also worth noting that 17 years have passed since their proposal.

Thus after finishing the last volume on women’s participation, the Escuelita in community had ended, and Héctor and I expressed our gratitude for the generosity showed by our maestro and his compañera (female partner) during the classes and our stay in the — community. We then met up with the other alumn@s (including Reyna) who had come together in the local assembly space and then departed for our hike to the access road at which we were to be picked up and returned by sand-trucks to La Realidad. Once the afternoon progressed into evening in the caracol, as more alumn@s continued arriving from other communities, the Zapatista teachers called us all back together once again for a final round of questions-and-answers, followed by the presentation of the Mexican and Zapatista flags and the singing of the anthems to State and EZLN, which in turn gave rise to more creative musical performances by the teachers and artistic interventions from alumn@s. I will confess that I cried for Sup Pedro when the maestr@s sang about this “simple” and “decent” man from Michoacán, born to a beautiful mother and killed in insurrection.

After the conclusion of the participatory cultural event, it was announced that all those desiring to return to San Cristóbal would be leaving in a caravan departing before dusk the next morning. Then the night was ceded to a large dance on the basketball court, as animated by a sustained series of ludic perfomances on marimba played by male BAEZLN of differing generations.

Fin de Año in Oventik

Presentation of Zapatista flag, 31 December 2013

Upon returning to San Cristóbal, I was already greatly missing Héctor; I hope we will stay in touch. I considered which of the 5 caracoles to visit for the New Year’s celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the armed uprising and launched myself to Oventik, the closest to San Cristóbal. After being admitted into the foggy caracol with a crowd of other visitors shortly after arriving, I placed my belongings in one of the classrooms of the escuela autónoma, as a new friend had just recommended to me, and we then made our way to the basketball court where live music was being played under a roof, protected from the rain. Standing on stage alongside Zapatista authorities and BAEZLN, the performers included highland indigenous musicians and conscious freestyle rappers from Mexico City, among others.

At a certain point in the evening, as the rain continued, the assembled Zapatistas performed a “political act” involving the marching presentation of the Mexican and EZLN flags and the public reading of the Revolutionary Indigenous Clandestine Committee’s (CCRI) declaration on the event of the twentieth anniversary of the neo-Zapatista insurrection, as performed by a Comandanta. The text was subsequently read in Tsotsil and Tseltal translations—with these being two indigenous languages spoken in the highlands region in which Oventik finds itself. In the Tsotsil translation, the word kux’lejal (“bodily pain”) could be heard uttered several times.

At the end of this “act,” with the retiring of the Mexican and Zapatista flags, representatives of the EZLN wished all those assembled in the caracol a happy new year, and they particularly wished all Zapatistas a joyful twentieth anniversary for their resort to arms. Similarly to the case in La Realidad just days before, the remaining hours of 2013 and the first several hours of 2014 in Oventik were celebrated with several hours of cumbia rebelde, during which the basketball court was full with dancers, Zapatistas and their well-wishers together. Also present at the cumbia were organizers of the Climate Caravan through Latin America (Caravana Climática por América Latina), who sought to connect the assembled dancing rebels with this compelling initiative from below to combine direct action and information-gathering activities in resistance to unchecked ecocidal trends.

Entrance to Oventik caracol, 1 January 2014

Questions, Critique, and the Future

There can be no doubt that the BAEZLN have been truly impressive in their efforts to “conquer liberty” and extend the cause of autonomy in the 20 years since their declaration of war against capitalism and the Mexican State. Nonetheless, it would contradict the spirit of critique and autonomy not to raise questions and concerns regarding different facets of the Zapatista movement. For one, what is the political model the EZLN is pursuing? As against the original demand for independence made in 1994, this model is not that of formal statehood—as is made, for example, in the Palestinian case—but rather that of developing the new society within the shell of the old. In his Developing Zapatista Autonomy (2009), German anthropologist Niels Barmeyer argues that the Zapatista example advances the creation of a counter-state to the official one presided over by the Mexican government (el mal gobierno).

Contemplation of the various details provided in the four volumes of text assigned to alumn@s of the Escuelita would seem to confirm this diagnosis, from consideration of the Good-Government Councils (as counterposed to the bad government) to the Zapatistas’ alternative health and education systems. As Barmeyer notes, moreover, the EZLN provides protection to its members, even if the organization does not necessarily exercise a monopoly on “legitimate” use of force in the territories of its influence.1 Nonetheless, if the overall claim is true—that the Zapatistas really desire a State, or that the nature of their principles of self-government effectively express their wish for such, as an anarchist confided in me at the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City a year and a half ago—one must then interrogate the attraction the Zapatistas have represented for libertarian socialists and anti-authoritarians the world over these past 20 years.

Clearly, the 1 January 1994 insurrection has proven seminal for the adoption of the Black Bloc tactic all over the globe, while the indigenous character of the movement and the radical humanism expressed by its principal spokesperson—Sup Marcos—have enlivened and illuminated the radical imaginations and hopes of millions of observers. But what do anarchists have to say about the processes of socio-political autonomy undertaken by the EZLN since January 1994? Are they too similar to State institutions, or are they sufficiently distinct? Is it just a matter of “contradict[ing] the system while you are in it until it’s transformed into a new system,” as Huey P. Newton observed with reference to the “survival programs” the Black Panther Party implemented in the late 1960′s, “pending revolution”?2

How are outsiders, especially internationals, to engage with the persistence of authoritarian and inegalitarian attitudes toward women in social movements putatively based on the principles of “democracy, justice, and freedom” with which they express solidarity—despite the relative improvements seen in these terms over time? Can it justly be said that feminist perspectives are simply irrelevant if they are held by those who do not pass the course of their lives within a given movement? If it were to be affirmed, the principle underlying this second question would betray a cultural nationalism and relativism of sorts, one which undermines internationalism and global notions of solidarity. It would also effectively trivialize the disappointment expressed from the start by many Mexican feminists at the perpetuation of patriarchy within the EZLN—and, indeed, paper over the absurd expulsion of COLEM (el Colectivo de Mujeres, or the Women’s Collective, from San Cristóbal) from Zapatista territory on the charge that its feminist organizing threatened to “incite a gender war”!3

Conceptually, the idea of “autonomy” cannot immediately tell us which of the conflicting principles is to be held superior: in the first place, autonomy likely should presume substantive freedom for all as a precondition of its existence, yet in practice it is taken to mean the outcome of popular self-determination, as opposed to Statist or capitalist imposition. Such tensions clearly exist in appraising Zapatismo, especially with regard to the situations faced by female and non-heterosexual BAEZLN. A similar critical line of thinking could also bring to light the extensive deforestation which Zapatista communities have produced through their “autonomous” desire to raise cattle en masse in jungle environments, or it could criticize the Zapatistas’s drinking and selling of Coca-Cola and their generally non-vegetarian lifestyles—or at least the ambivalence Marcos expresses as regards the prospect of even discussing this latter point, for he declares vegetarian tactics of moral suasion to be an imposition to be disobeyed. As Mickey Z. Vegan could be expected to point out, the collective Zapatista butcher-shop from the Roberto Barrios region mentioned in volume III may not be the most liberating project to engage in, for either BAEZLN workers or the beasts themselves.

Thus, in spite the issues I have observed and the doubts they produce in me, I consider the EZLN nothing less than a world-historical revolutionary movement, one which has played a critical role in inspiring and spurring on the multitudinous activist militancy seen throughout much of the world following the self-implosion of the Soviet Union—a militancy which radically seeks the abolition of those power-groups which threaten the entire Earth with social and environmental catastrophe. I also believe that the EZLN’s struggle has much more to offer the world still—given that the Zapatistas had originally sought to incite other Mexican revolutionary groups to join them in insurrection in 1994, and in light of the continued strength of the capitalist monster against which the BAEZLN revolted—no matter how optimistic Marcos’s declaration last year on the occasion of the new Baktun and the silent Zapatista occupation of the townships the EZLN had taken in 1994, that the world of those from above is “collapsing.”

However, I do agree with Sup Marcos that the world of those from below is resurging. Hence was I very glad to have been able to attend the first course of the Escuelita and to celebrate the twenty years since the Zapatista insurrection together with them. I wish the BAEZLN the very best for this year, and the next 20 as well. ¡Zapata vive!

Javier Sethness Castro is a translator and author of two books who worked as a human-rights observer in Chiapas and Oaxaca during 2010. His current project is to complete a political and intellectual biography of Herbert Marcuse. Visit his blog on libertarian eco-socialism here.

Notes

1) Niels Barmeyer, Developing Zapatista Autonomy: Conflict and NGO Involvement in Rebel Chiapas (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 2009), 5, 214.

2) Cited in Alondra Nelson, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 63.

3) Barmeyer 99-100, 206.