by John Barnes / MLive

John Koski walks near cattle bones on his Matchwood Township farm Thursday, Oct. 10, 2013. The 68-year-old, who has a second cattle farm in Bessemer, has the highest number of reported wolf attacks in Michigan. Koski supports the upcoming Upper Peninsula wolf hunt. (Cory Morse | MLive.com)

Use this searchable database for details on wolf attacks from 1996 to now.

It is a mythical animal. Inspiring. Feared. Intelligent. Reviled.

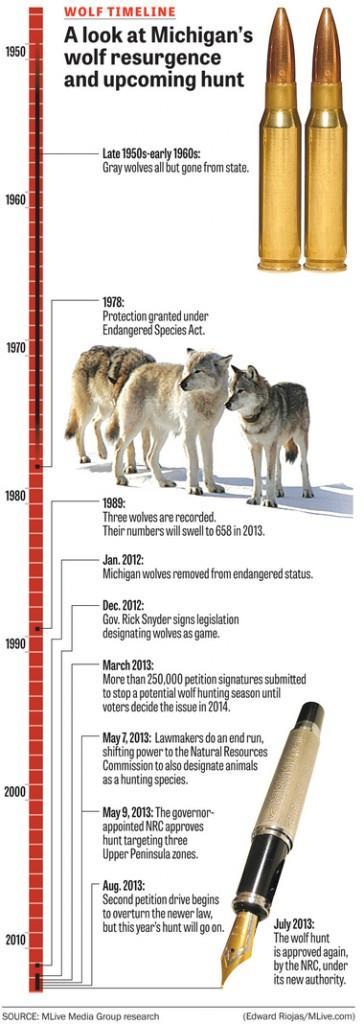

Once on the brink of extinction, the gray wolf’s comeback in Michigan is remarkable.

And now we will hunt them, a historic first in the state.

But an MLive Media Group investigation found that half-truths, falsehoods and a single farmer have distorted reasons for the hunt. Among them:

• When state lawmakers asked Congress to remove wolf protections, they cited an incident in which three wolves were shot outside an Upper Peninsula daycare center where children had just been let out. That never happened, MLive found.

• A leading state wolf specialist said there are cases where wolves have stared at humans through glass doors, ignoring pounding on windows meant to scare them. That never happened as well. The expert now admits he misspoke.

• The Natural Resources Commission received more than 10,000 emails after seeking public comment, but there is no tally of how many were pro or con. The NRC chairman deleted several thousand, many of them identical, from all over the world. Most of the rest went unopened, a department spokesman said. They said anti-hunt groups launched an email blast so extensive the agency was overwhelmed.

• And while attacks on livestock are cited as a reason to reduce wolf numbers, records show one farmer accounted for more cattle killed and injured than all other farmers in the years the DNR reviewed.

The farmer left dead cattle in the field for days, if not longer, a violation of the law and a smorgasbord that attracts wolves. He was given an electric fence by the state. The fence disappeared. He was also given three “guard mules.”

Two died. The other had to be removed in January because it was in such poor condition.

In wolf circles, those problems are known. Lesser known is that they persist. Wildlife officers again in May found dead cattle on his farm, MLive learned under a Freedom of Information Act request.

Visiting reporters in October also saw a months-old cow carcass in an open barn.

The farmer has never been cited. Nor is the state seeking restitution for the fence or mules.

“We’re kind of washing our hands of him,” said Brian Roell, a state Department of Natural Resources wildlife biologist in Marquette.

The farmer has received $38,000 from the state to pay for his cattle losses, MLive’s analysis shows, plus $3,000 for the mules and fence. That’s more than all other farmers combined.

Such incidents swirl like muddy water through the raging current of the wolf-hunt debate. Hunt supporters say they are isolated incidents and the hunt is necessary.

“How much exposure do we have to be subjected to before there is a problem? If they eat somebody, does that change the game?” asked Andres Tingstad, chief district judge of Gogebec and Ontonagon counties and a pro-hunt advocate.

Such questions will face voters across the state next November. One referendum, possibly two, will be on the ballot.

In coming days, MLive will explore the farmer with the most cattle losses, the town at the center of the debate, the daycare incident that is a Michigan myth, and the hundreds of thousands of dollars pouring into the state to make the first hunt the last hunt.

‘The smartest dog you ever raised’

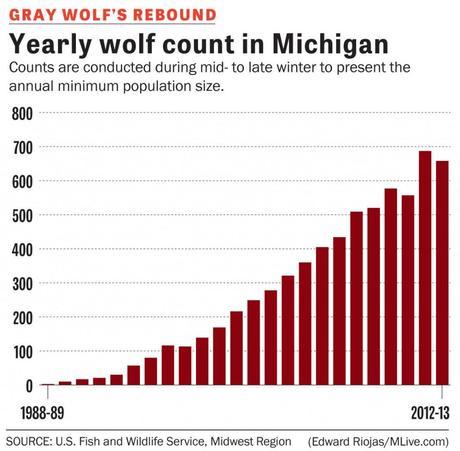

Officially, there are a minimum 658 wolves in the Upper Peninsula. That’s well up from three counted in 1989, after bounties and poaching eliminated wolves decades earlier.

Because of their comeback, here and in Wisconsin and Minnesota, the federal government removed protections in January 2012 – opening the door for Michigan’s Nov. 15 hunt.

Licenses sold out in six days, 1,200 in all. Forty-three wolves can be shot in three Upper Peninsula zones where officials say they have caused the most problems.

It is a touchy subject, including in Ironwood, where wolves have entered the city in search of deer and been shot by wildlife officers.

“It’s split pretty much, even here,” said Ralph Ansami, outdoor writer for the Ironwood Daily Globe.

Wolves share a mystique embedded deep in the American soul. They are independent. Packs are rooted in family units. They learn. They survive.

“Wolves are like the smartest dog you ever raised,” said Don Lonsway, a wolf specialist in Ironwood for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services “If they killed on one farm once, they will bypass others to kill there again.”

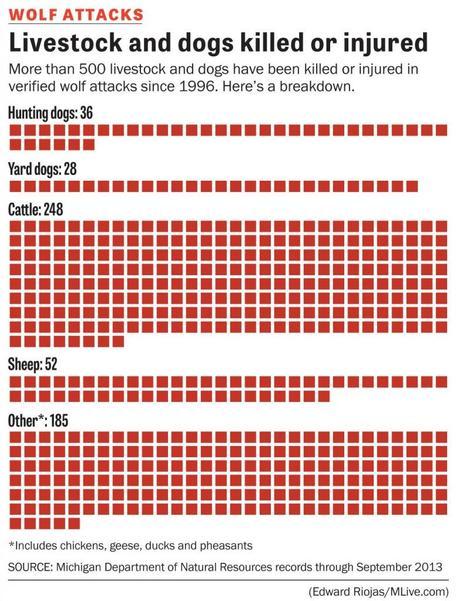

The first verified attack after wolves disappeared from Michigan was in 1996, when a free-ranging bear dog was killed in Luce County in 1996. Since then, there have been nearly 300 verified attacks on more than 500 livestock and dogs – half in just the past three years.

Calves are usually the target. On May 24, 2012, a cow and calf were both killed in Ontonagon County as the mother was giving birth. That is not the first time.

This wolf was killed on the Ontonagon County cattle farm managed by Duane Kolpack.Courtesy photo/Tom Dykstra

‘Sometimes they’re shopping, sometimes they’re buying’

Duane Kolpack, of Ontonagon County, says he has lost dozens of cattle to wolves on his 1,200 acres, especially since 2010 when predations picked up.

He’s tried non-lethal deterrents – guard mules, firecracker shells. When wolves were delisted last year, hunters with permits could kill wolves on his property. They’ve taken eight.

He or others can also shoot a wolf attacking cattle. But how do you prove that? he asks.

“It’s like when your wife goes shopping and she’s circling around. Will she buy anything? The wolves are the same. Sometimes they’re just shopping, and sometimes they’re buying.”

But attacks on livestock involve more than cattle:

•Forty 10-week-old Ring-necked pheasants were killed in August 2008 in Luce County.

•Thirty-eight geese and 12 ducks were killed a month later in Ontonagon County.

•Thirty-five chickens were killed in February 2006 in Alger County.

Tougher than rocket science

Nancy Warren, who has worked with wolf experts on both sides of the issue as part of the state’s Michigan Wolf Management Roundtable, says the hunt is unnecessary.

“The facts speak for themselves and it just shows this is all politically motivated and has nothing to do with science,” said Warren, Great Lakes regional director for the National Wolfwatcher Coalition.

She points to what she calls misrepresentations by some in the DNR , Natural Resources Commmission, and the Legislature.

Adam Bump, the state’s fur bearer specialist, allows he misspoke when he gave an interview to Michigan Radio that was broadcast in May.

“You have wolves showing up in backyards, wolves showing up on porches, wolves staring at people through their sliding glass door while they’re pounding on it exhibiting no fear,” Bump told the NPR affiliate.

That did not happen, he concedes. But the fear in certain areas is real, Bump said. He also said not making a choice is the same as making a choice, and that the DNR used rigid science to identify areas with problem wolves, leaving other packs alone.

He allows there are no guarantees the hunt will have an impact, and recalls the advice a professor once gave him at Michigan State University.

“Wildlife management is not rocket science,” Bump said. “It’s much harder than that.”

A farm like no other

Here, in his cattle pasture, John Koski is surrounded by white pine, tamarack and golden aspens that shimmer in the wind. And cattle of course.

Not all of them are alive.

This farm is part boneyard. Cattle rib cages litter his land, pelvises too. Bleached white skulls glimmer in the sunlight on a warm autumn day. A decaying carcass lies in a shed, months after it died.

The bones are not supposed to be here because the law requires the animals to be buried.

They are not supposed to be here because cows should not be wolf bait.

They are not supposed to be here because we have too many wolves, hunting advocates say.

In Michigan’s great debate over whether wolves should be hunted, no farmer is more controversial than this 68-year-old man with blue eyes and a thick Finnish accent.