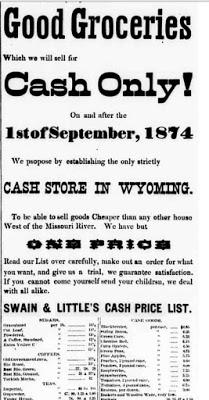

Apparently Swain & Little's public brawl didn't hurt their business.

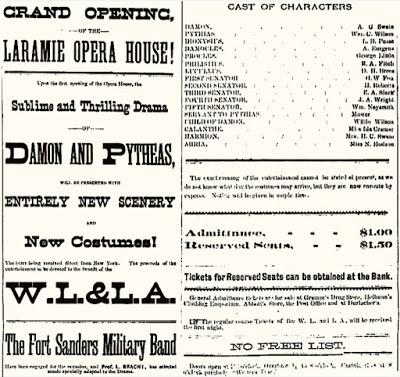

On a chilly February evening in 1874, Laramie grocer A.G. Swain stepped before a large crowd and declared: “There is no public virtue left!” He was forced to shout over the ensuing uproar. “Silence! Your throats offend the quiet of the city!” This so angered Geo. Little, his business partner that Little ordered a sword-brandishing horde to attack Swain. But W.M.C. Wilson, proprietor of the Brunswick Billiard Hall, showed up just in time. With his superb swordsmanship, he defeated the horde and saved his dear friend Swain.Was this just another confrontation in the rough-and-tumble young town? Were Swain and Little settling a grocery dispute in true frontier style? Not at all! This was the grand opening of the Laramie Opera House.

“Opera” brings respect

By the 1870s, opera houses were common in the West. So great was the desire for decent entertainment that any town near a railroad had one. But most were operatic in name only. “Theater” was more appropriate but “opera house” sounded more respectable—a sign of transition from frontier to civilized society.

On February 23, 1874, just six years after Laramie was established, a large ad appeared in the newspapers: “GRAND OPENING OF THE LARAMIE OPERA HOUSE! Entirely New Scenery and New Costumes!” However, the costumes were still en route from New York, so the date had not been set.

The audience was enthusiastic and appreciative, as was the case whenever local talent took to the stage. “The universal verdict is that [the performers] succeeded beyond everybody’s most sanguine expectations” according to the Daily Sentinel. The play was far better than expected, or even possible for a company of amateurs.

The location of the Laramie Opera House now seems to be lost. Nor do surviving newspapers reveal who owned it, or how it came to be. But once operational, it was regularly in the news. Laramie sat on a major east-west rail line, and had ready access to traveling entertainment—popular drama, lectures, novelty shows, comedy, concerts, travelogues and more.

Quality was not guaranteed, however. Sometimes the “orchestra” turned out to be a piano player, or the “troupe” a single actor. But that was the exception. “Usually the touring companies had a good voice or two among them, and the melodies alone were worth the price of admission. What good luck for a country child to hear those tuneful old operas sung by people who were doing their best,” recalled author Willa Cather, from her girlhood in Red Cloud, Nebraska.

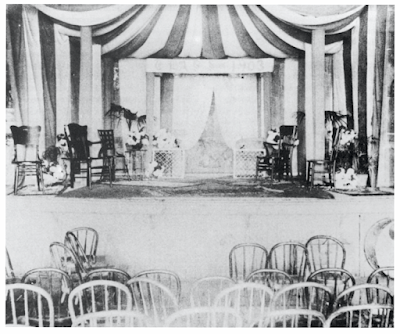

Opera House in Red Cloud, Nebraska, c. 1903. Nebraska State Historical Society.

Lecturess and martyr

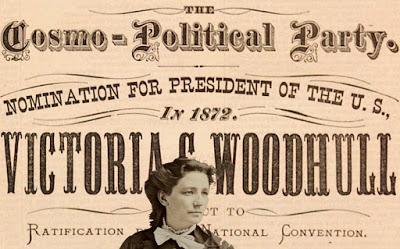

Among the highlights of 1874 was a lecture by Victoria C. Woodhull, well-known suffragette and proponent of ‘free love’ (a woman’s right to divorce). She was freshly out of jail, having been arrested for sending obscene literature through the mails, specifically a widely-read article about the affair between Henry Ward Beecher— popular pastor of a fashionable New York church—and the wife of his good friend Theodore Tilton.

Victoria C. Woodhull was nominated for president by the Equal Rights Party in 1872 (though women could vote only in Wyoming and Utah). Headline from Woodhull & Claflin Weekly, April 22, 1871; added photo by Matthew Brady, c. 1870.

When the charges were dropped six months later, Woodhull promptly hit the lecture circuit, drawing tremendous crowds. “Her subject will be a review of the Beecher-Tilton Scandal, entitled ‘The Naked Truth.’” The Daily Independent was adamant: “Mrs. Woodhull is highly spoken of as a lecturess of fine talents, and also as a martyr who has been sadly traduced by her prosecutors ... We advise our citizens to go and hear the lecture.”Ireland comes to Laramie

In October, another nationally known act appeared at the Opera House—Healy’s Hibernian Gems. This well-known first-class troupe will present “a magnificent panorama of Ireland, on which is delineated nearly all the cities, towns and splendid ruins” announced the Daily Independent.

Hibernicons—Irish panoramas—were popular novelties of the time. These were early moving pictures, with sound! Healy’s 10,000-foot long canvas was attached to two spools; a hidden operator turned one, causing the other to unwind. As each of the 85 scenes appeared on the stage, the narrator served as tour guide while musicians, actors and comedians provided Irish-themed entertainment.

The Opera House also hosted dances, political and religious meetings, graduation exercises, trials, wrestling matches and more, with events regularly in the news. But after April 1875, they inexplicably disappeared, making the end of the Laramie Opera House as mysterious as its beginning.

High society gathers in a Thespian temple

In May of 1884, the famous German-American actor Daniel E. Bandmann and his troupe arrived in Laramie, shortly after returning from a five-year 700-performance world tour. Though best known as a Shakespearean, Bandmann was equally skilled in other genres. His leading role in the popular drama Narcisse was especially admired. No wonder high society was all aflutter—Bandmann would perform Narcisse in Laramie!

German-American Shakespearian actor Daniel E. Bandmann; date unknown (before 1905). Harvard Theater Collection.

On May 12, Herr Bandmann stepped on stage before “fashionable, cultivated and critical” citizens from Laramie, Cheyenne and Rawlins. The Laramie Boomerang proudly noted that the ladies were dressed “in the latest style and most elegant costumes, while the gentlemen, in many cases, appeared in full evening dress.” They were given delicately perfumed programs, skillfully designed by George Garrett, the Boomerang’s typographer.The first act was “rather tame” but when Bandmann made his appearance in the second, as Narcisse Rameau, the mood changed entirely. His account of the terrible wrongs inflicted upon him, and “his subsequent bursts of histrionic pathos” brought warm and vigorous applause.

While he was just a young scholar, Narcisse Rameau’s wife had left him to become Madam Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV. But virtue triumphed in the end. Madam P died and fell into the arms of the husband she had abandoned. Narcisse lived happily ever after with his new wife—the young, clever and beautiful actress, Doris Quinault. “Doris” was played by Louise Beaudet, herself a young, clever and beautiful actress. She also was co-owner of the theater company, and, infamously, Bandmann’s mistress.

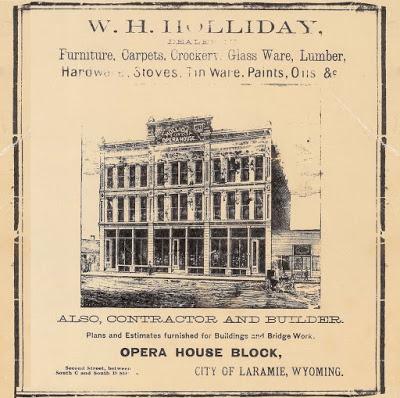

The occasion for Bandmann & Beaudet’s Narcisse was the grand opening of the Holliday Opera House, above Holliday’s store and offices on the east side of Second, between today’s Garfield and Custer. A successful merchant and builder, W.H. Holliday spent between $20,000 and $55,000 on the project (reports vary).

Only first-class opera house between Omaha & Salt Lake City

The Daily Sentinel declared the new opera house to be “the only building and stage between Omaha and Salt Lake City for the rendering of first class dramas and spectacular scenes.” It was designed and supervised in person by stage architect H.W. Barbour, formerly employed by the Union Square Theater and Grand Opera House in New York, as well as theaters in Colorado, and Central and South America.

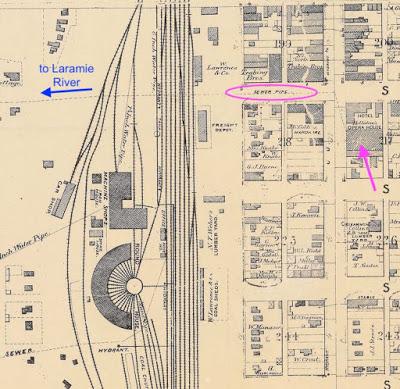

Holliday Opera House c. 1885. The building burned to the ground in 1948, in the great Holliday Fire, which destroyed much of downtown Laramie. From 1885 Laramie City map; Laramie Plains Museum.

The Opera House occupied the entire second story of Holliday’s building, with a 36-foot high ceiling, 70 x 36-foot stage, and seating for 700-800. The stage included a drop curtain featuring the Bay of Naples at sunset, and a full set of 12 x 20-foot “flats” [scenes]: Kitchen, Parlor, Prison, Garden, Horizon, Dark Wood, Rocky Pass, Snow Scene and more (18 total). Painted by Sosman & Landis of Chicago, they were “as fine as may be seen anywhere in the world” (Laramie’s press was reliably complimentary).In marked contrast, the lighting was old tech—kerosene lamps, notoriously hazardous with their open flames. Many large lamps were installed, but even so, the light was dim; nor could it be adjusted once lit. When performing in lamp light, actors resorted to heavy makeup and exaggerated movements to connect with the audience.

But just a year later, a Boomerang reporter watched in amazement as new lights came on in Holliday’s Opera House. “As one row after another of burners were lit overhead and about the walls, the footlights and finally the chandeliers—the hundreds of jets of pure steady flame set burning—the great improvement became manifest.”

Coal or “town” gas moved through a system of pipes controlled with wheels and levers, making the lights easily adjustable. “There was no hitch during the whole evening though several changes of light were made.” But the open flames made gas lights just as risky as kerosene lamps. Though electricity was much safer, Holliday considered gas “better adapted to such a place than electric illumination.” Perhaps electric lights were still too expensive.

Note sewer line running from Holliday's Opera House (pink arrow) to river. A second one starts near the Union Pacific's Round House. They were recent additions, mainly for storm runoff, a serious problem in this part of town. From 1885 Laramie City map; Laramie Plains Museum.

Opera comes to the Opera House

In January of 1886, the Boomerang had exciting news. The Milan Grand Italian Opera Company, with full chorus and orchestra, would present Donizetti’s popular tragedy “Lucia Di Lammermoor”—in the original Italian! “Reserved seats will be on sale Monday morning at 9 o’clock. Carriages may be ordered at 10:30 ... the Company’s Librettos, in English and Italian, will be for sale by the ushers.”

The review the next day underscored the aspirations of small towns with their opera houses: “It is to be hoped that the success of this company will enable us to have a regular season of Italian opera every year, and thus educate the masses to a general appreciation of this style of music.”

Another opera house fades from the limelight

In 1893, the lighting in Holliday’s building was upgraded to electricity. But by then, it had been years since an earnest actor stepped onto the brightly lit stage before an eager audience. Holliday had closed his opera house in 1887. “It was quite a blow,” lamented the Boomerang. Laramie needed an opera house, “both as an advertisement for the [town], and for the pleasure of the citizens.”

Fortunately, Maennerchor Hall also offered many fine performances, and another opera house did open, in the 1890s. But these are stories for another day. Laramie’s long rich ‘operatic’ history can’t be squeezed into a single article!

Postscript: This is my final article in a series for the Laramie Boomerang's "Laramie History" column. We volunteers have been contributing weekly to help the paper during hard economic times, and to provide an alternative to covid news. It has been a pleasure!

Editor Judy always complains about my head shot, so I sent her a this as a joke.

She used it, and readers liked it! Hmmm ...