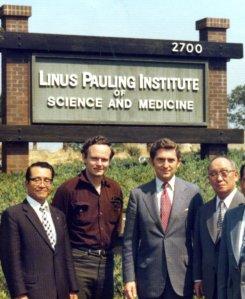

Art Robinson and Rick Hicks with LPISM visitors, 1977.

[A history of the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine, Part 2 of 8]

By the end of 1975, the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine found itself teetering on the brink of financial collapse. Linus Pauling was donating his entire salary and even personal funds from his bank account to LPISM, and every employee had taken meaningful pay cuts. Everyone involved realized that the organization could not hope to succeed if business was to continue as usual.

An important change came in March 1976, when Richard Hicks was hired to help with fundraising. This move proved to be a windfall as Hicks interjected new energy and ideas into the search for additional income. One of the Institute’s most important employees for many years, Hicks rather quickly utilized his talents to help alleviate the extreme financial problems of 1975. With Hicks on board, the Institute was only treading water, but the imminent threat of drowning had lessened.

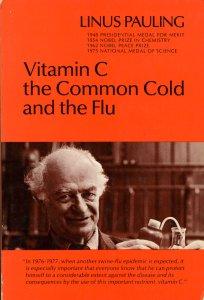

Later in 1976, Pauling published Vitamin C, the Common Cold, and the Flu, an updated version of his earlier book Vitamin C and the Common Cold. The book sold reasonably well and managed to bring some much needed cash in to LPISM, though not as much as the organization had hoped. Additionally, Ewan Cameron and Pauling published another paper on vitamin C and cancer, which stated that terminal cancer patients lived longer and enjoyed a higher quality of life when given supplemental vitamin C.

Just as conditions were starting to improve, the Institute suffered another major setback when investigators from the National Cancer Institute visited LPISM to check on the progress of its hairless mice skin cancer study. In their report the investigators frowned upon the Institute’s tiny staff, what it deemed to be bad management by its administrators, and Pauling’s frequent absences. Their harsh judgement helped to “sink the Institute’s future grant requests” for many years afterward, thus forcing LPISM to redouble its efforts to secure new sources of private funding.

On the research front, Art Robinson began working with Kaiser-Permanente to set up a national sample bank with tens of thousands of blood and urine samples that LPISM could utilize for better research. The collaboration was moving along smoothly until Kaiser realized that the bill for the project would be in the neighborhood of $5.8 million, at which point Kaiser decided to scrap the deal in a most expedient fashion. In 1977, a year after negotiations had started, Robinson was informed that the plan was rejected because it was too ambitious and vague.

Robinson wasn’t the only one receiving that response. Pauling had been seeking grant funding from the NCI from the moment that its investigators’ report had been released. He reasoned that if the NCI was complaining that LPISM was too small, then they should give him more money to expand. By 1977 he had been turned down four times by the organization, each time under the auspices of his proposals being too ambitious and vague.

In light of the bad press that accompanied the NCI’s dismissals, Pauling sent copies of his proposals and rejection letters to twenty-four members of Congress, including the senators heading the committees on health and nutrition, Ted Kennedy and George McGovern respectively. He received no response, and in turn asked his lawyer if he could sue the NCI for bias. His lawyer advised him that there was no legal precedent for such a case, and that the chances of successfully suing a federal agency were “less than slim.”

Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl, 1986.

In early 1977, LPISM hired two people, both of whom ended up making major contributions to the Institute. First they hired Emile Zuckerkandl to lead their research on genetics. Zuckerkandl brought a different type of personality to the Institute. He and his family had fled Austria shortly before the onset of World War II, as they were wealthy and Jewish. In fleeing they had managed to bring with them some of their rare artwork collection, which Zuckerkandl would show to his coworkers at LPISM from time to time. A renowned scientist, Zuckerkandl had worked previously with Pauling at Caltech, collaborating and co-developing a theory of molecular evolution.

The second person of note to be hired was Stephen Lawson, who was brought on board to assist with direct-mail solicitations for fundraising. Lawson’ s position was very much at the entry level. When he was hired he was not associated with the Institute in any way, and his only concrete knowledge of Linus Pauling harkened back to a chapter during his student days at Stanford University, when he saw Pauling protesting the firing of a tenured instructor.

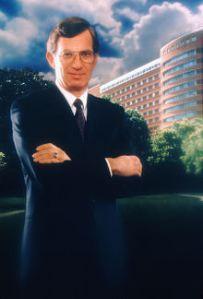

About this time, the NCI also brought someone in: a new head named Vincent DeVita. He was more open-minded about Pauling and his vitamin C work, and was aware of how much public support Pauling had accumulated. As a result he consented to speak with Pauling and, after a multi-hour meeting, agreed to set up a conclusive clinical trial on vitamin C and cancer. When asked about the apparent reversal of the NCI’s opinion of Pauling’s work, DeVita responded that Pauling “can be a very persuasive man.” By March DeVita had arranged for the trials to be carried out at the prestigious Mayo Clinic, headed by the esteemed Dr. Charles G. Moertel. Pauling and DeVita met again in April to discuss the details of how the trial would be conducted.

Vincent DeVita, 1999.

On the eve of the Moertel study, circumstances appeared to be improving across the board for the Institute. With more apparent support for his research, Pauling expanded his program and in 1977 began a new series of tests designed to determine the effect of vitamins on tumor growth. The tests utilized 600 hairless mice as subjects. Additionally, LPISM managed to acquire enough funds to hire a professional direct-mail company for fundraising, and was able to place a number of successful advertisements in major financial periodicals including Barron’s and the Wall Street Journal. With these changes, LPISM saw a hefty boost in its incoming funds.

Buoyed by the success of the direct-mail strategy, LPISM began focusing its fundraising on this type of marketing. The move proved to be very effective and non-governmental donations increased from 50% of LPISM’s funding to 85% -the organization received almost $1.5 million in private donations in 1978 alone. For the first time in its short history, LPISM wasn’t suffering from financial hardships.