They say natural history is dying. Support is in steep decline. There are fewer academic programs, staff are cut, museums and herbaria are shuttered. What a huge mistake! This is knowledge that's critical “for fields as varied as human health, food security, conservation, land management and recreation” as well as pleasure. But fortunately there’s a counter-trend and it’s huge too. Just look online – natural history is experiencing a come-back! Given the times, it’s not surprising that the savior is digital.

Citizen science isn’t digital per se. It's any “scientific research conducted, in whole or in part, by amateur or nonprofessional scientists”. It could be the amateur botanist who regularly adds plant specimens to the regional herbarium. But the reasons why citizen science is so popular are digital: online resources make it a lot easier than it used to be; and it's social.Social media also are not digital per se. Long drives to visit friends, telephone calls, postal letters, email messages, blog posts, texts … being such social creatures we love them all. But these days social media are defined more narrowly: “computer-mediated tools that allow people to create, share or exchange information, ideas, and pictures/videos in virtual communities and networks” ... for example, iNaturalist.

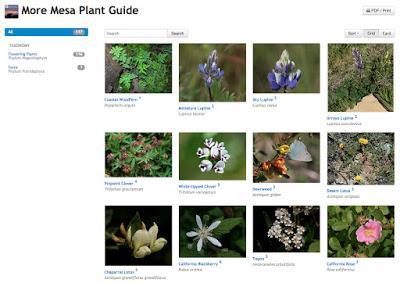

Several years ago I was looking online for information about plants in Santa Barbara County, California. I found the More Mesa Plant Guide – one of many guides available at iNaturalist.org. This one is especially cool:

Twelve of the 117 plant species in the More Mesa Plant Guide (click on image to view).

As I write this, iNaturalist includes 1,643,600 observations – reports of plants and animals of all kinds from specific locations around the world. Observations can be organized into projects – “a way to pool your observations with other people on iNat. Whether you're interested in starting a citizen science project or just keeping tabs on the birds in a nearby park with your local birding club, Projects are the way to go.”They convinced me (not hard) and I put together Plants of the Southern Laramie Mountains, Wyoming:

“The southern Laramie Mountains are a treasure for naturalists. I go there regularly, and photograph the plants I see. I started this project to store my observations and those of others -- please contribute! My hope is that it will be useful to anyone interested in the area's flora.”

With enough observations and photos, I will be able to compile a guide to the plants of the area. This is the dream.

Nodding onion (Allium cernuum).

Miner's candle (Cryptantha virgata).

Heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia) may be a damn yellow composite, but the leaves make it easy to recognize. It's common in the Laramie Mountains.

Heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia) may be a damn yellow composite, but the leaves make it easy to recognize. It's common in the Laramie Mountains.

Setting up the project was easy; populating it is another matter (no fault of iNaturalist). These are the problems so far:

1. Wind. I need photos for a plant guide, but plants don’t stand still in wind, and it’s often windy in the Laramie Mountains. Maybe I should have done a rock project.

2. Time. I haven't hiked as much, with my camera, as I thought I would.

3. Other participants. This is the biggest obstacle by far.Only a few people have added observations. Maybe I'll launch some kind of advertising campaign when the project is farther along. I also need help with identification.

Citizen science relies on crowds for both data collection and accuracy. If I add an observation of water birch, iNaturalist ranks my identification “Casual” until someone agrees, at which point it becomes “Research”. If they disagree, calling it bog birch, it becomes simply a birch, as we both say it’s a birch. Another botanist may jump in and say “yes indeed, it’s a river birch” at which point it becomes a Research grade observation of a river birch. [The iNat algorithm for choosing among multiple identifications “is a little convoluted” – read more here.]

I found river birch (Betula occidentalis) in Curt Gowdy State Park, in early spring.

I found river birch (Betula occidentalis) in Curt Gowdy State Park, in early spring. I may be an expert; I may take specimens and photos to the herbarium for verification. But until an iNaturalist user agrees with me, my identification remains Casual. Thus unless one lives where there are lots of botany geeks (like the Santa Barbara area), a project advances slowly. Verifications are hard to come by. Observations trickle in.

I may be an expert; I may take specimens and photos to the herbarium for verification. But until an iNaturalist user agrees with me, my identification remains Casual. Thus unless one lives where there are lots of botany geeks (like the Santa Barbara area), a project advances slowly. Verifications are hard to come by. Observations trickle in.

Rocky Mountain spikemoss (Selaginella densa).

There’s a good reason for iNaturalist's quality control step. Identification to species is one of the biggest sources of error in citizen science (see Gardiner and colleagues 2012 for examples). “Small or cryptic organisms” are especially problematic, but there are plenty of bigger ones that are just as tricky. Birders have LBJs (little brown jobs), while we botanists deal with DYCs – the damn (or disgusting) yellow composites of the sunflower family. And they’re hardly the only challenging plants. Yesterday I spent 30 minutes studying herbarium specimens of our local wild geraniums so I could put a name on my iNaturalist observation.

Geranium caespitosum.

Geranium id is easier than it used to be. Multiple species were recently lumped together into Geranium caespitosum because they were so hard to tell apart. The two geraniums above and below were growing within two meters of each other in sagebrush grassland.

This is Geranium caespitosum too.

Citizen science provides two major benefits in my opinion. The obvious one is massive amounts of data, though we need to improve quality control. But what excites me most is how engaging it is. Many people are now active naturalists because of online resources, and because of the social aspect. We collect, identify, and share – more than we ever could have dreamed of doing in the past. And in at least some cases, participation in citizen science has strengthened commitment to conservation, leading to further environmental action (Thelen and Thiet 2008).

Even the experts do it! Source.

There are apps for it, of course.

Naturalists used to be a small group of adventurous eccentrics. Now lots of us can be nature geeks ... another example of democratization thanks to the internet.

Are we reincarnations of the amazing naturalists of the 19th century American West? AHC.

Have you done citizen science? What do you think?

Sources (in addition to links in post)Gardiner, M. and colleagues. 2012. Lessons from lady beetles: accuracy of monitoring data from US and UK citizen- science programs. Front Ecol Environ 10: 471–476.Thelen, BA and Thiet, RK. 2008. Cultivating connection: Incorporating meaningful citizen science into Cape Cod National Seashore’s estuarine research and monitoring programs. Park Science 25(1).