by Lou Zucker / Roar Mag

In the wake of the Gezi Park protests earlier this year, a new movement is now underway against the construction of a third bridge over the Bosphorus.

A wide breach has been cut into the forest. On the very day that activists trying to save the last green refuge in Istanbul’s center were first evicted from Gezi Park, trees started to be cleared on a massive scale just outside the city. Free from the ever-alert public gaze of the Istanbullus — few city dwellers venture into this large forest — the machines working here are preparing the grounds for a major construction project which will have a drastic environmental impact on the city: a third bridge over the Bosphorus.

Despite the fact that this is miles away from the iconic Taksim square and the city’s buzzing center, the destruction of the forest does not pass entirely unnoticed — and not without resistance either. One Sunday morning, the first day of December, activists have come by bike or on foot, carrying banners and signs; ready to enter the Belgrad forest north of Istanbul. Some even join the protest by para-glide. Their aim is to see to what extent the destruction has proceeded, to share this information with the public and to let the government know that every step towards the construction of the third bridge is under critical observation. Later, the demonstration will proceed towards the Water and Forest Ministry.

According to Kuzey Ormanları Savunması of the Northern Forest Defence, the activist group coordinating most of the protest against the third bridge, two million trees will have to be felled for the construction. This roughly equals to one third of the forest in Istanbul’s north which has not already been overrun by the city’s ferocious growth. The consequences are well known: increased threat of floods, destruction of local ecosystems, and degradation of the climate. Another two million trees less that will be unable to contribute to the CO2-compensation of this metropolis of at least 14 million inhabitants, which is already suffocating due to the heavy traffic every day — the mere thought makes it hard to breathe.

But these are only the short-term consequences. The new bridge, as Professor Bülent Akgül (name has been changed, ed.) points out, is part of an even bigger infrastructure project: a six-lane highway just north of Istanbul. The trees that will have to give way for the construction of the bridge are just the beginning: in the long run the bridge and the new highway will result in the city’s expansion towards the north. The still existing forests and watersheds in this area could already be gone or contaminated during the next ten years, the professor estimates.

The plans for the development of the third bridge and the subsequent destruction of the surrounding natural environment are a deformed and undemocratic replacement of the urban growth strategies as developed by the Istanbul Metropolitan Planning office, back in 2009. Akgül explains that these plans consisted of directing urban growth towards the east and west, using new subway connections as incentives, in order to protect the watersheds and forest areas in the north of the city. Even though these urban strategic plans themselves might be questioned, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government has chosen to bluntly ignore the suggestions elaborated under the academics’ participation.

In the short term, the third bridge and the new highway would divert the cargo traffic and relieve the constant congestion on the second bridge. But it is not a secret, the professor adds, that every new road creates its own traffic. With the construction of the second bridge, the commute between the continents rose dramatically: according to Kuzey Ormanları Savunması, the number of people crossing the Bosphorus daily by bridge increased by only 170 per cent, while the number of vehicles increased more than tenfold. Both professor Akgül and the activist group agree that the only solution for Istanbul’s traffic problem can be the expansion of the public transport network, especially by subway. Most of the congestion on the bridges is being caused by private cars, which only transport a third of the people.

As though the mega project alone wasn’t enough of a provocation, Erdoğan has decided to name the new bridge after Yavuz Sultan Selim, a 16th century Ottoman sultan known for massively persecuting and killing Alevites. The religious minority of Alevites has voiced its opposition against naming the bridge after such a controversial historical figure, raising the issue formally in the political arena, and informally on the streets during both the Gezi Park protests and later demonstrations.

Who, then, benefits from the third bridge? Unsurprisingly, it’s primarily the big construction companies, as well as the government itself, which — as far as the forest defenders are convinced — keeps up friendly relations with these companies and will also profit from the contract. Akgül believes that with short-term victories like these Prime Minister Erdoğan tries to shed a good light on his administration while he is actually causing grave long-term damages to the city.

Again, it is trees that bring people to the street, just like in the beginning of the Gezi uprising this summer. And again, it is about a lot more than just the trees. Efe Baysal, a PhD candidate at Bilgi University and one of the Kuzey Ormanları Savunması activists, explains: “Many people were just angry about Urban Renewal Projects — government intervening in daily life and the economic system — yet we were unable to do anything. Gezi Park brought hope, and when you have hope and anger combined, there you have resistance.”

Two military coups, as well as several interventions, succeeded in leaving society depoliticized, suffocated in resignation and discouragement. Now, Baysal observes, people are getting politically active again, building up new networks and experimenting with new forms of organization and protest.

One of Kuzey Ormanları Savunması’s most peaceful actions was stopped by police forces close to Taksim square. At the end of September, around twenty activists dressed up as trees and walked down the busy Istiklal Street in a very slow, even meditative way, accompanied by bird’s singing out of portable speakers. The rows of armed police officers blocking their way, backed by several water cannons, once more illustrated the absurdity of the government’s reaction to peaceful protest.

The forest defenders have, of course, not stopped to resist Erdoğan’s authoritative “urban renewal projects” in different creative ways. Apart from their performance in the central shopping street, they have visited and protested on the construction sites of the third bridge, they have united with other groups and organizations in the environmentalist camp, they have spoken with people living in the neighborhoods and rural areas that will be most directly affected by the project, and they are currently realizing a survey on how much Istanbul’s inhabitants actually know about the construction and its consequences, while at the same time raising awareness.

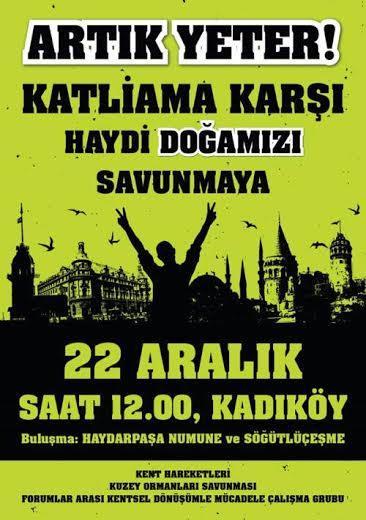

The next step will be a big demonstration on December 22, with the goal of reclaiming the city, which many different organizations and neighborhood forums are organizing together, among them Kuzey Ormanları Savunması. The mass mobilizations shaking the country during the summer might have ceased, but according to activist Baysal the hope they brought about seems to have endured even after the vanishing of teargas. He likes to refer to the forest defense group of which he is a part as “a child of Gezi Park”.