Equisetum hyemale is an able colonizer in spite of its lazy sporangia. Nevada roadcut, Matt Lavin photo.

Do you know the horsetails, also known as scouring rushes, genus Equisetum? They are curious plants, with slender hollow jointed green stems and no leaves (or so it appears). They're usually associated with water, but some make their way into human habitats—yards, pastures, and roadcuts for example. A small patch grows in my yard, next to the curb and gutter.

Equisetum's simple beauty. Unbranched species are often called scouring rushes. Andre Zharkikh photo.

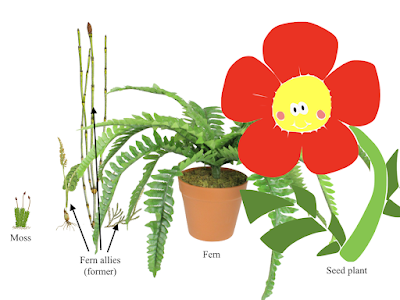

Equisetum was once a member of the fern allies, along with moonworts, club mosses, spike mosses, and several other curiosities. Together with ferns, they sat between mosses and seed plants on the evolutionary ladder, having vascular tissue but no seeds. But because these plants looked very different from ferns and were poorly understood, they were thrown into a single catch-all group, even though they were diverse in appearance and structure.Progress in evolution, left to right. The moss has no vascular tissue, so stays near the ground (source of water). The fern allies, fern, and flower are vascular plants, but only the flower is a seed plant.

Several decades ago, new knowledge did away with the fern allies group. Some members now reside in their own group, while others, including Equisetum, were combined with ferns. The expanded fern group was subdivided to accommodate the distinctive new members. The common familiar ferns of yore are now called true ferns for lack of a better name (leptosporangiates is the scientific name).Though horsetails are technically ferns, their leaves differ radically from those of true ferns. In fact, at first glance it appears there are no leaves. But there are—just highly modified. Whorls of leaves occur at each node (not to be confused with branches in branched species). They are fused into a sheath that looks very much like the stem. The tips remain separate, forming a ring of "teeth" at the top of the sheath (deciduous in some species).

Tan sheaths are fused leaves, topped with a ring of black leaf tips (teeth). Matt Lavin photo.

Field horsetail, E. arvense, is a branched species. In the absence of green leaves, photosynthesis occurs in the stems and branches. Andre Zharkikh photo.

In Equisetum, spore-producing sporangia reside in cones at tips of fertile stems. In field horsetail, fertile stems are flesh-colored. Green branched sterile stems emerge later.

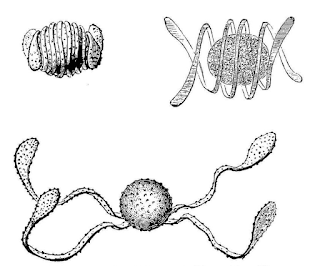

For effective dispersal, horsetails rely on the spores themselves. Each one is wrapped in four ribbon-like appendages called elaters. Sensitive to humidity, they uncurl and curl back up with drying and wetting. Until recently, their exact function was unknown. It was thought that elaters probably acted like wings, helping spores fly with the wind.

Uncurling elaters of a horsetail spore. Source.

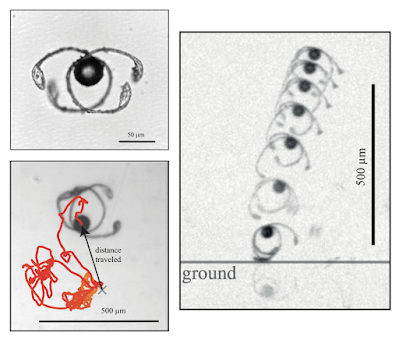

Then Marmottant and colleagues (2013) followed horsetail spores with a high-speed camera. They discovered that elaters function not as wings but as legs. Elaters allow spores to walk, and even better, to jump high enough to catch the wind!

Spores "walk" by extending their elaters with drying, and then shifting a little when humidity increases and the elaters curl back up. This is more like a random meander than a walk (image below), but it can get a spore out of tight situation, like being stuck to something.

If for some reason elaters can't gradually uncurl as they dry, elastic energy builds up until the stress is too great. Then suddenly the elaters uncurl, launching the spore. It may jump a full centimeter off the ground! This is a large distance compared to its size, and enough to catch a ride on windy days.

Spores can hop repeatedly because hopping doesn't damage the elaters. The authors of the study speculated that because jumps occur with drying, they are a way to escape from dry locations, hopefully to places with more moisture. The authors also "believe that this study will inspire new biomimetic classes of self-propelled objects ... ". Will groceries one day hop to our doorstep?

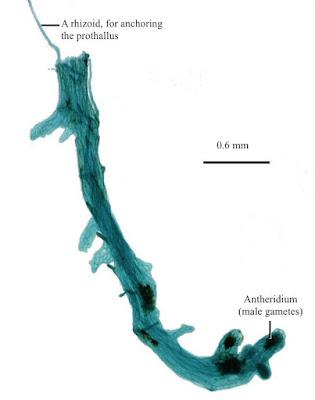

If a spore lands in a suitable spot, it will germinate not into a horsetail like its parent, but a prothallus, the gametophyte or sexual plant that is part of the life cycle of all ferns. For a simplified version of the full story, see my previous post "Fern Seeds?"

Equisetum gametophyte; those of true ferns are typically heart-shaped or bilobed. Source.

Sources

Llorens, C, et al. 2015. The fern cavitation catapult: mechanism and design principles. J. R. Soc. Interface 13: 20150930. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2015.0930

Marmottant P, Ponomarenko A, Bienaime ́ D. 2013 The walk and jump of Equisetum spores. Proc R Soc B 280: 20131465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.1465

Moran, Robbin. 2004. A Horsetail's Tale? in A Natural History of Ferns. Timber Press.