Hand prints are often left at crime scenes and, if a suspect is generated, the crime scene print can be compared with one obtained from the suspect. If a match is made the suspect indeed left the print at the scene. But what if there is no suspect? Nothing to compare the print with. Here a description of the perpetrator can be very helpful. But what can a single hand print tell us about what the person looks like?

A recent study by forensic anthropologist Professor Daniel Franklin and his team at the University of Western Australia suggests that the height and possibly the sex of the perpetrator can be estimated from the print.

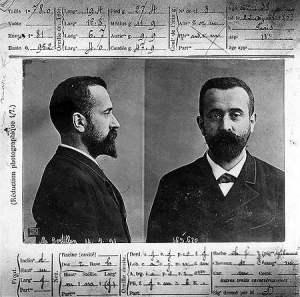

This harkens to the days of anthropometry, or bertillonage as it was termed. By the end of the 19th century, fingerprinting had not yet been fully accepted and vied with Anthropometry and Bertillonage as the standard identification method in criminal investigations.

Anthropometry (anthrop means human; metry means to measure) is the study of human body measurements for anthropological classification and comparison. Simply put, it is the making of body measurements in order to compare individuals with each other.

French police officer Alphonse Bertillon believed that the human skeleton did not change in size from about age 20 and that each person’s measurements were unique. He also believed that people could be distinguished from one another by key measurements, such as height, seated height from head to seat, length and width of the head, right ear length, left little finger length, the width of the cheeks, and other measurements. He created a system of body measurements that became known as bertillonage. According to Bertillon, the odds of two people having the same bertillonage measurements were 286 million to one.

His greatest triumph came in February 1883, when he measured a thief named Dupont and compared his profile against his files of known criminals. He found that Dupont’s measurements matched a man named Martin. Dupont ultimately confessed that he was indeed Martin.

For years, this system was accepted by many jurisdictions, but early in the 20th century flaws became apparent. Measurements were inexact and subject to observer variation since measurements in two people who were of the same size, weight, and body type varied by only fractions of a centimeter. The measurement system wasn’t exact enough to make such distinctions. The final blow to the Bertillonage system occurred with the famous Will West case.

Though landmark in its importance, the Will West case was more a comical coincidence. On May 1, 1903, Will West entered Kansas’ Leavenworth Penitentiary, where the records clerk thought he looked familiar. West denied ever having been in the prison. As part of his intake examination, anthropometry was performed and officials were surprised to find that Will’s measurements matched those of another inmate at Leavenworth named William West. The two men did look eerily similar, but each stated that they did not know each other and that they were not brothers. Fingerprints were then used to distinguish between the two Wills after which Leavenworth immediately dumped anthropometry and switched to a fingerprint-based system for identifying prisoners. New York’s Sing Sing Prison followed a month later.

Was the similarity between Will and William West simply a bizarre coincidence? Not really. A report in The Journal of Police Science and Administration in 1980 revealed that the two were likely identical twins. They possessed many fingerprint similarities, nearly identical ear configurations (unusual in any circumstance except with identical twins), and each of the men wrote letters to the same brother, same five sisters, and same Uncle George. So, even though the brothers denied it, it seemed that they were related after all.