Yellowstone National Park -- land of wonders both natural and unnatural.

No matter how carefully one plans a vacation, sometimes things just don’t work out. Most years, late August is a wonderful time to be in the high country. Bugs are few. Crowds, so to speak, are dwindling. And the weather’s good ... most years. But this year it wasn’t. There was rain and then more rain and finally snow.One day we headed to nearby Yellowstone National Park, with the hope that bad weather would ameliorate summer hassles. No such luck. There were the usual crowds, stressed-out visitors, and traffic jams for charismatic mega-fauna. I tried hard not to let these annoyances obscure the natural wonders, and I mostly succeeded.

Remains of a shallow sea that used to cover western Wyoming.

The first stop was not far from the Northeast Entrance, where Madison limestone is exposed in a road cut. Fossils are common enough to qualify it as “fossil hash”. This was a shallow sea 350 million years ago and apparently teeming with life -- brachiopods, crinoids and other critters. Their remains were preserved in limy mud that became the Madison. It’s widespread in Yellowstone, but is largely covered by thousands of feet of volcanic rock from Absaroka volcanos 50 million years ago, as well as the more famous catastrophic eruptions just 600,000 years ago. The Madison limestone probably is the main source of material for travertine in the Park, for example at Mammoth (see end of post).

Fossil hash.

The road cut is part of Vignette # 3 in Marc Hendrix’s Geology Underfoot in Yellowstone Country (highly-recommended). It was easy to get to, and the hunt was fun. Fossils were abundant as promised, but I took only photos. Collecting is prohibited in National Parks.

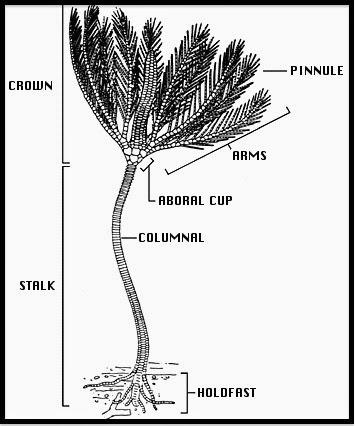

Reconstructed crinoid, from The Tree of Life.

Here’s a mystery fossil -- could it be a crinoid calyx or crown? This is just a guess so if you find this photo in an online search, don’t use it!

We continued down Soda Creek to the Lamar Valley. Its beauty was sublime -- the river meandered through broad grasslands with dark conifer forests and volcanic rocks on the slopes above. It went on for miles. Rain and mist added to the beauty, but kept me from taking photos.

The Lamar River Valley on a clear day, from Yellowstone’s Photo Collection (NPS).

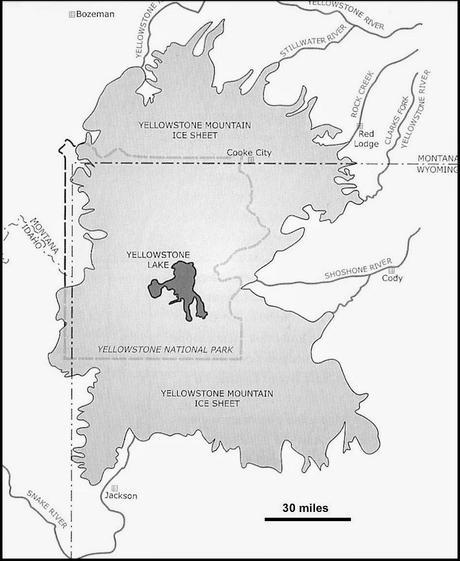

The rain let up a bit as we approached Tower Junction. We stopped just past a bison jam to check out glacial kettles in a hummocky ground moraine. Yellowstone was very much glaciated during the Pleistocene, under hundreds of feet of ice. This was the Yellowstone Mountain Ice Sheet, the largest ice mass south of the continental ice sheet (Carson 2010). Glacial features abound in parts of the Lamar Valley -- kettles, moraines and erratics galore.

Extent of the Yellowstone Ice Sheet, based on Carson 2010. Click on image to view.

Kettles form when blocks of ice break off the front of a retreating glacier and then melt in place. Now 12,000 years later, the kettle below supports healthy wetland vegetation, a pond and a pair of ducks.

Erratics on hummocky terrain. This ground moraine is part of Geology Underfoot Vignette #15.

At Tower Junction, we turned onto the “Grand Loop” and joined the frenzy that is Yellowstone in summer ... even on rainy days. Fortunately geology, ecology and photography kept me from going insane. I scanned road cuts as we passed through the “core of an ancient volcano” -- Mount Washburn is one of the Absaroka volcanos of 50 million years ago. We stopped near Dunraven Pass, where the effects of the great Yellowstone fires of 1988 were obvious and striking. Many dead trees were still standing, even after 26 years. And young lodgepole pines were growing thick like weeds.

Lodgepole pine saplings thrive amid the standing dead.

There were many many many acres of dense young lodgepoles (Pinus contorta).

At Norris Geyser Basin I took a short hike to investigate some of the hydrothermal features for which Yellowstone is famous, and for which the Park was created (1872). The scenery was wonderfully bizarre, and the colors were great, even under gray skies. Trails were in use but not crowded. People strolled, chatted, speculated, laughed and took photos free of care. There must have been many wet iPhones and iPads that day!

"Could we cook our fish in it?" -- Veteran Geyser.

"It smells like a stink bomb!" Indeed, lovely Emerald Spring reeks of sulfur!

Sweethearts stroll through the geyser basin. All trails are on boardwalks.

Hoping for a really big spurt from Steamboat Geyser. It's the tallest in the world ... when it's active.

Thin sheet of flowing water. Bacteria, algae and non-biological precipitates color the geyser basin.

Cistern Spring

Pool of Echinus Geyser.

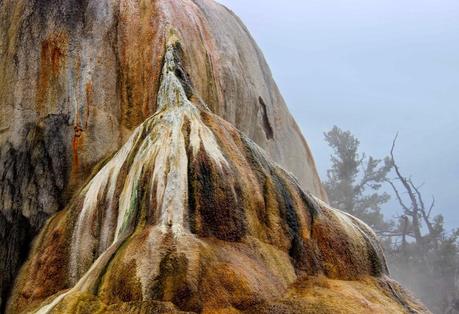

The sounds were really eerie. Sometimes there was no obvious source, just a low rumbling underground. It was easy to believe I was walking on the roof of Hades. I tried to capture sounds with movies, but they weren’t nearly as impressive as the real thing. Here are two of the louder features I came across.We finished at Mammoth, famous for hot springs and spectacular terraces. I thought back to the first stop of the day at the outcrop of Madison limestone -- probable source of carbon dioxide and calcium carbonate from which these travertine features are built.

Looking down on Mammoth from travertine terraces off the Upper Terrace Loop.

By the time we reached the trailhead it was getting late. The sun, which hadn’t done much all day, was now threatening to set. I hurried along the boardwalk to a spot with active terrace growth (flowing hot chemical-laden water), and thus great colors.

Old travertine is shades of gray and tan. Active areas seem so colorful in comparison.

Then I found another neat spot ...

This cascade of pools and small terraces was incredible. The textures were as wonderful as the colors.

Bryan, TS. 2008. The geysers of Yellowstone, 4th ed. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.Carson, RJ. 2010. East of Yellowstone; geology of Clark’s Fork Valley and the nearby Beartooth and Absaroka Mountains. Sandpoint, ID: Keokee Books.Hendrix, MS. 2011. Geology underfoot in Yellowstone country. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Co.Lageson, DR and Spearing, DR. 1988. Roadside geology of Wyoming. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Co.