“Anyone can cut and run, but it takes a very special person to stay with something that is stupid and harmful.” – George Carlin

Bouldering at one’s limit involves suspension of disbelief. At first the holds seem unmanageable, the sequence too cryptic, the moves too big. With enough hubris, confidence, or simple hard work, the climb begins to open up. Suddenly, one has completed a brand new set of moves. One has proven oneself equal to the challenge provided by nature and a first ascentionist. One has earned another tick in the guidebook.

Great climbing literature is based on this titanic struggle of human flesh upon unfeeling, unflinching stone. In The Boulder: A Philosophy for Bouldering, Francis Sanzano correctly states that

…one can learn all one needs to know about another by watching them boulder. We can discern if they are a fighter, if they make good decisions, if they are good under pressure…as if the skirt of consciousness has been lifted and they remain in the act, struggling like death before us.

Boulders are the canvases upon which we may paint moments of greatness. But that’s not what I want to talk about. I want to talk about the opposite. I want to talk about what happens when an easy-looking boulder problem turns you around, yanks your pants down to your knees, and spanks you…or as I like to call it, “getting Thunderballed.”

Sometimes we try boulder problems not because they are at our physical limit, but because every problem is different, and novelty of movement is just as valuable as “trying hard.” A couple of weeks ago, Vikki, Rachel, Ian, James and I ventured into the North Walls to try Thunderballs, a Top 100 V5. It’s a clean, vertical wall with a few small, positive edges on it. V5 is a tough grade, but all of us have done harder problems. The problem looked straight-forward enough. We all thought we’d do it quickly and move on.

The climb took us 5 hours.

David calmly bests the many cruxes of Animal Magnetism (V7).

The great Thunderballs session of 2013 was an emotional rollercoaster of epic, twisted proportions. It was Rachel’s last day, and her skin was a little thin from so much climbing. Her second attempt had her past the crux, matching a good hold, and about to go to the lip, when her foot popped and she was on the ground. Ian fondled the holds and declared that he wasn’t going to try it…ever. James tried once and said he was done. I was psyched, if for no other reason than to tick another Top 100, but the crux right hand crimp was sharper than I was anticipating, and I couldn’t find the balance to move off of it.

After a few tries, Rachel threw in the towel. “Last go…” Not wanting the session to end, Ian put his shoes on and gave it a go, figuring out a key foot sequence. Vikki started trying too, and Rachel had no choice but to keep giving it a “last try,” over and over and over…three hours later, the sky was beginning to darken, nobody had climbed the problem, our right middle and index fingers were all either bleeding or close to it, yet we were unwilling to submit that climbing this piece of stone, theoretically well within all of our abilities, might not happen.

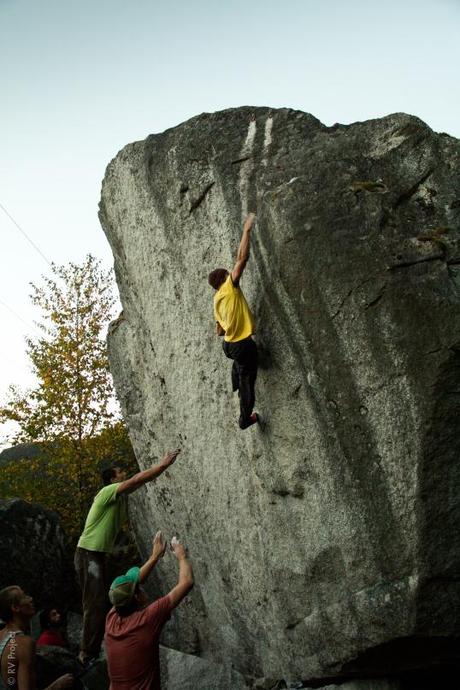

The author on the first physical crux of Ride the Lightning (V8). The first mental crux is to try the problem in the first place.

Francis Sanzano might do well to explore these situations. Five climbers drastically underestimate a challenge. How will they react? I’ve been around a lot of bouldering areas and I’ve seen a lot of similar situations. A typical reaction is to quit and move on to something more easily attainable, or at least easier on the ego. Another that I’ve seen is spite, which involves the climber(s) denigrating the quality of the rock, the holds, the guidebook description, the guidebook author’s mother, conditions, and anything else dubiously connected to failure. Most significantly, I’ve noticed in myself and others a tendency to impatience (“I just want to get this over with”), which results in a breakdown in bouldering fundamentals. The climber doesn’t rest enough, doesn’t carefully brush the holds, doesn’t clean their shoes, doesn’t study and refine his or her movements. The climber loses the process. When this happens in a big group, the whole session can fall apart.

The Thunderballs session kept going strong. I figured out that if the key fingers are taped, the crux razorblade crimp didn’t hurt and in fact would bite into the tape better than our skin. This meant that Rachel, who had been gushing from her tips for two hours, could give the climb a few more goes. James, who had not put his shoes on since his first attempt several hours earlier, got psyched again and started trying. After having announced his retirement a second time, Ian Cotter-Jordan made another comeback and climbed to the top, proving that there was no bad juju, no hyper-gravity vortex…just a challenge. (I promised Ian three beers if he did it that go…I think that helped.)

I freshened my finger tape and sent the line too, on one of my many, many “last tries.” Vikki surprised everyone, most of all herself, by climbing past the crux and into the better holds above, falling at the same point that Rachel had several hours previously. All of a sudden, the psyche was high again. Rachel was giving it her all on every go, convinced that it would be her last. There was always someone to convince her to rest a few minutes and try again, and in this way the session went on.

Having also thrown in the towel several times, the big Aussie we call James taped up his mitts and sent the problem by headlamp. He called it the send of his trip (and his trip has included Rocklands). We all hooted and hollered, as much out of relief and shared joy as out of the ludicrousness of the situation; five people sitting on uncomfortable rocks, trying a painful climb, for four hours.

Rachel and Vikki continued to try, and Rachel got very close a great many times, but ultimately came away empty-handed. After a total of five hours, we picked our way down the dirty talus and back to the truck.

As we nursed our wounds at Wendy’s, we joked that “Thunderballs is the best V5 in Squamish…maybe in North America.” We decided that any time we approach a problem that looks easy or is graded as such, and we end up in a titanic struggle, it would be referred to as “Getting Thunderballed.”

There is no such thing as a crappy boulder problem. There’s just rock. Some go to school to study the composition and history of it, some paint or draw formations of it, some grind it up for roads, and some choose to climb it. We as boulderers have assigned an arbitrary, consensus-defined numerical value system to physical difficulty, but ultimately we choose to climb rocks because we like to choose our own adventure. Sometimes the “crux” isn’t a particular move: it’s conditions, or fear, or pain, or endurance, or focus. We may choose to focus on any number of cruxes. What we ultimately seek is to master our bodies and minds by pitting ourselves against challenges and overcoming them. And bouldering offers infinite challenges.

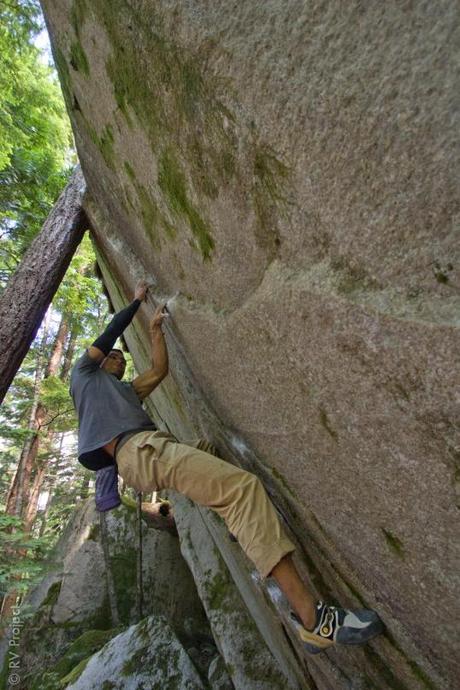

Eric Bissel overcoming the slick, polished holds to send Wormworld (V6).

One cannot overcome a challenge by avoiding it. A bouldering ticklist is a set of goals, and is unique as such because most goals and dreams don’t come with difficulty ratings. Run a marathon, write a novel, learn how to play an instrument…all are arbitrary challenges we set for ourselves, unrelated to basic survival. The most impressive people are the ones with a diverse set of skills and experiences, evidence of facing challenges. It’s not that they make it look easy, it’s that getting there was hard. What if the only questions in life were “are you eating food, breathing air, drinking water, and reproducing?” We need challenges because life is empty without them.

A few days ago, Jesse, Colin, Jeremy, myself, and Aussie James went to a problem called Catch a Swollen Heart for Not Rolling Smart, a cool-looking V7. It’s a vertical face with positive crimps leading to a sidepull up high and a big, balancey move to the top. It looked like a version of Thunderballs with bigger holds. Jeremy and I planned on flashing the climb and moving on to a sport project we have.

Predictably, all of us struggled hard on the surprisingly sharp and powerful climb. Not one of us completed it, though we threw ourselves at it for nearly three hours. We were thoroughly Thunderballed. And we stuck with it. I felt some temptation to curse the guidebook author, to convince myself that a hold had broken, to find a “better problem.” We all expressed confusion about how it could be so hard. But we had chosen this challenge, and we learned from it that we all could use some practice with smaller holds and technical movement. And if nothing else, persevering, maintaining composure, and trying hard in the face of an epic Thunderballing was an exercise of true grit that will serve us all for years to come. Even if no scorecard can track it.