Margaret Armstrong often used plant motifs, in this case the Coast Range Mariposa Lily (1); source.

By 1913, American graphic artist Margaret Armstrong had all but abandoned her successful career in cover design. It's true that Art Nouveau, whose flowing undulating lines she found so inspiring, was falling out of fashion, and that cheaper printed paper dust jackets were replacing decorative covers. But these trends were largely coincidental. Armstrong gave up her career for a very different reason. She was writing a book about her passion—the wildflowers of the American West.

Armstrong family c. 1910s; Margaret lower right (source).

Margaret Neilson Armstrong was born in New York in 1867 to a wealthy and artistic family. Her father, a diplomat, studied oil painting while in Italy, and also worked in stained glass, as did her sister Helen. Margaret started her career as a graphic designer in the 1880s, and by 1890 was specializing in book covers and bindings. She produced covers in her popular distinctive style for at least 270 books, including works by well-known authors such as Washington Irving, Henry Thoreau, Henry Van Dyke and John Greenleaf Whittier, as well as the popular botany books of Francis Theodora Parsons (aka Mrs. William Starr Dana).

Armstrong marked her covers with the monogram “MA” (upper right corner). Winding banner reads: "New leaf, new life, the days of frost are o’er" (source).

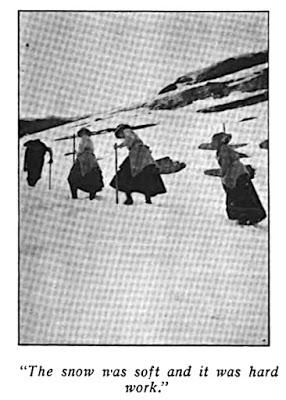

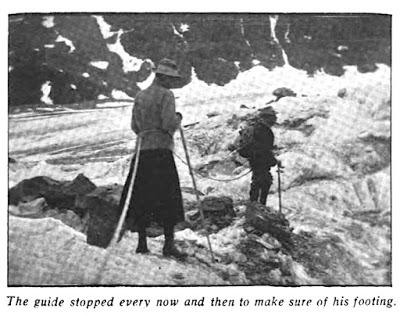

By 1908, Armstrong’s output began to decrease noticeably as she devoted more and more time to her passion for plants. This wasn't terribly surprising to those who knew her, for she had been an enthusiastic naturalist since childhood (2). Things got exciting in 1911, when Armstrong (then in her mid-forties) and three gal friends toured the American West, seeking adventure as well as plants. They rode horses down into the Grand Canyon, and crossed the Victoria Glacier above Lake Louise to climb to the Mitre Col (see her 1912 article). While they weren’t the first women to accomplish these things (3), they were operating far outside the norm, and enjoyed themselves immensely for it.

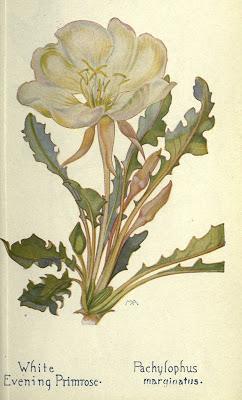

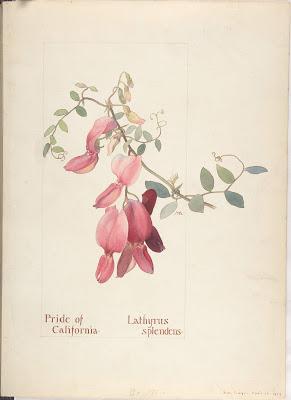

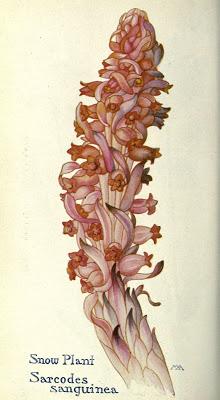

Armstrong continued to travel the western United States—studying, sketching and collecting wildflowers. None of the existing field guides adequately covered the area west of the Rocky Mountains (4), and she was eager to produce one herself. But as she noted, “the field is vast, including within its limits all sorts of climate and soil, producing thousands of flowers, infinite in variety and wonderful in beauty, their environment often as different as that of Heine's Pine and Palm” (quotes here and below are from Armstrong's Field Book). Out of this multitude, she chose some 550 of the more common species for her book—from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, California, Nevada, Utah and Arizona.

Let's look at some of her chosen subjects

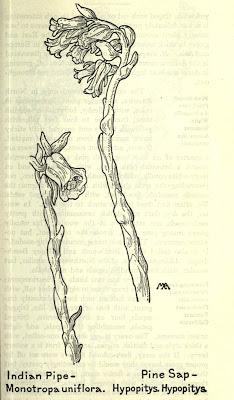

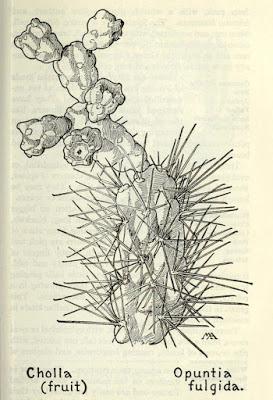

(images from BHL Western Wild Flowers Flickr album unless noted):

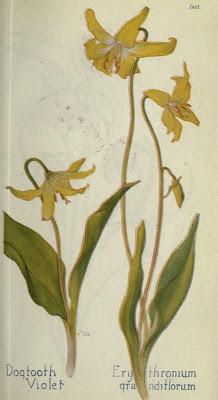

Erythronium grandiflorum pushing "right through the snow" (source).

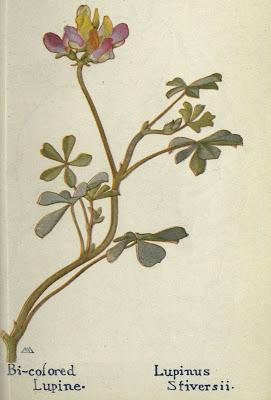

Lupinus stiversii (source).

Monotropa uniflora (source).

Cylindropuntia fulgida (source).

I learned of Margaret Armstrong and her wildflower book only recently, by way of Flickr where the color plates have been uploaded by Biodiversity Heritage Library. They’re available for download, are copyright-free, and have been tagged (partly by yours truly) so that they will come up in searches (scientific name, common name, artist name and more). If you’re looking for a fascinating citizen science opportunity, checkout BHL on Flickr for more information.

Notes

(1) The Coast Range Mariposa Lily, Calochortus vestae, was C. luteus var. oculatus in Armstrong’s day. She considered mariposa lilies to be the most characteristic flowers of the West. “They grow freely all through the West, as far north as British America, and down into Mexico, but they never get east of Nebraska, so these gay and graceful flowers may be considered the peculiar property of the West.” C. vestae was “one of the most beautiful of all the Mariposas.”(2) Armstrong had no formal training in botany.(3) Armstrong and her companions are sometimes referred to as the first white women to reach the bottom of the Grand Canyon. But from her account of the trip, it’s clear that others had gone before. She included a story told by their guide of a female tourist who refused to ride back up to the rim, and had to be hauled out on a litter.(4) In her Preface, Armstrong states that hers “is the only fully illustrated book of western flowers, except Miss Parsons's charming book, which is for California only” (Wild Flowers of California by Mary Elizabeth Parsons, 1900). She doesn’t mention Rocky Mountain Flowers by Frederic and Edith Clements, published in 1914—possibly too late to be noted in her book. In any case, Armstrong didn't include species found only in the Rockies.(5) Armstrong recruited a small army of botanical experts for help with identification and nomenclature. In her acknowledgements, she noted that “Professor J. J. Thornber, of the University of Arizona, is responsible for the botanical accuracy of the text and his knowledge and patient skill have made the book possible.” She thanked eight experts on the flora of the western United States for “most valuable assistance in the determination of a very large number of specimens …” and eight others for advice and assistance (including luminaries such as Alice Eastwood, WL Jepson, Marcus Jones and NL Britton).Sources

Armstrong, Margaret. 1912. “Canyon and Glacier” in The Overland Monthly ser. 2 v. 59. Available here courtesy HathiTrust.

Armstrong, Margaret. 1915. Field book of western wild flowers. London,C. [sic] P. Putnam's Sons. Available here courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library.