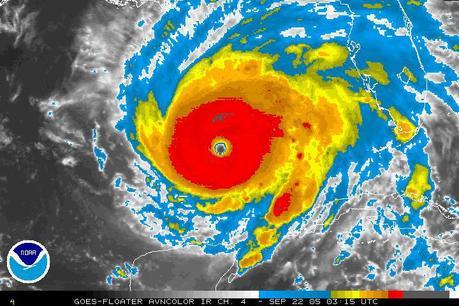

Hurricane Rita (2005)

by Jason Samenow / Washington Post

People don’t take hurricanes as seriously if they have a feminine name and the consequences are deadly, finds a new groundbreaking study.

Female-named storms have historically killed more because people neither consider them as risky nor take the same precautions, the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concludes.

Researchers at the University of Illinois and Arizona State University examined six decades of hurricane death rates according to gender, spanning 1950 and 2012. Of the 47 most damaging hurricanes, the female-named hurricanes produced an average of 45 deaths compared to 23 deaths in male-named storms, or almost double the number of fatalities. (The study excluded Katrina and Audrey, outlier storms that would skew the model).

The difference in death rates between genders was even more pronounced when comparing strongly masculine names versus strongly feminine ones.

“[Our] model suggests that changing a severe hurricane’s name from Charley … to Eloise … could nearly triple its death toll,” the study says.

Sharon Shavitt, study co-author and professor of marketing at the University of Illinois, says the results imply an “implicit sexism”; that is, we make decisions about storms based on the gender of their name without even knowing it.

“When under the radar, that’s when it [the sexism] has the potential to influence our judgments,” Shavitt said.

To test the hypothesis the gender of the storm names impacts people’s judgments about a storm, the researchers set up 6 experiments presenting a series of questions to between 100 to 346 people. The sexism showed up again.

Respondents predicted male hurricanes to be more intense the female hurricanes in one exercise. In another exercise, the hurricane sex affected how respondents said they would prepare for a hurricane.

“People imagining a ‘female’ hurricane were not as willing to seek shelter,” Shavitt said. “The stereotypes that underlie these judgments are subtle and not necessarily hostile toward women – they may involve viewing women as warmer and less aggressive than men.”

Hurricanes have been named since 1950. Originally, only female names were used; male names were introduced into the mix in 1979.

Given the implications of this work, the study authors’ suggest the meteorological community re-consider the merits of the storm naming practice.

“Although using human names for hurricanes has been thought by meteorologists to enhance the clarity and recall of storm information, this practice also taps into well-developed and widely held gender stereotypes, with unanticipated and potentially deadly consequences,” the study says. “For policymakers, these findings suggest the value of considering a new system for hurricane naming to reduce the influence of biases on hurricane risk assessments and to motivate optimal preparedness.”

The National Hurricane Center, while declining to specifically comment on the results of this study, emphasized the people should focus on storm hazards, irrespective of their names.

“Whether the name is Sam or Samantha, the deadly impacts of the hurricane – wind, storm surge and inland flooding – must be taken seriously by everyone in the path of the storm in order to protect lives,” said Dennis Feltgen, National Hurricane Center spokesperson. ”This includes heeding evacuation orders.”

Bill Read, a former director of the National Hurricane Center from 2008-2012, isn’t convinced the gender of the storm name is as big a factor in storm fatalities as the study purports.

“While necessary to eke out the gender difference, it leaves me with the need to know is this factor significant, or is it very minor in the mix of all other societal and event driven responses,” Read said.

Other voices within the meteorological community believe the study is important but stopped short of recommending an overhaul of the naming system.

“I am not ready to change the naming system based on one study, but it may be one more indicator that thinking exclusively about physical science is not enough in 2014 and beyond to save lives,” said Marshall Shepherd, past president of the American Meteorological Society.

Gina Eosco, a researcher at Cornell University’s risk communication group, emphasized the storm name is just one of many non-weather factors that behavioral scientists need to better understand in understanding how people make decisions when dangerous storms threaten.

“The focus on the gendered names is one factor in the hurricane communication process, but social science research shows that evacuation rates are influenced by many non-weather factors such as positive versus negative prior evacuation experiences, having children, owning pets, whether a first responder knocked on your door to tell you to evacuate, perceived safety of the structure of your home,” Eosco said. “None of these very important variables were factored into this study.”

Julie Demuth, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who studies societal aspects of weather information, echoed Eosco’s call for more research into the social and behavioral aspects of decisions people make in the face of a storm.

“My hope is that this paper helps continue the dialogue about and support for research on people’s hurricanes risk perceptions and responses and the implications for hurricane risk communication,” Demuth said.

Jason Samenow is the Capital Weather Gang’s chief meteorologist and serves as the Washington Post’s Weather Editor. He earned BA and MS degrees in atmospheric science from the University of Virginia and University of Wisconsin-Madison.