Dysfunctional relationship visible just left and above mid-photo; closer view below.

Dodder has other names, many of which reflect its parasitic nature, for example Witch’s Hair, Witch’s Shoelaces, Devil’s Hair, Devil’s Guts. Damage to the host varies, from minor to deadly, and some dodder species are serious agricultural pests (1).

Dodder stems tightly twine around anything within reach.

When I enlarged this photo, I saw I had captured flowers and fruit! (click on image to view)

Toothed petals are source of specific epithet denticulata (S. Matson, Attribution-NonCommercial license).

If dodder finds itself on an appropriate host (verified by chemical sensing), it tightly twines around stems and leaves, growing haustoria in the process—projections that penetrate the host’s vascular tissue.

Developing haustoria of Cuscuta gronovii (courtesy BlueRidgeKitties, some rights reserved).

Haustorium of Cuscuta reflexa in shoot of Nicotiana benthamiana (Kaiser et al. 2015).

But to live the easy life of a freeloader, dodder must first overcome a major challenge—establishment. Its seeds germinate indiscriminately, no matter where they land (seeds of some parasitic plants germinate only in response to chemicals from suitable hosts). Even worse, a dodder seedling has no roots and little in the way of embryonic food reserves, so it must find a host soon, within just a few days (2).It would seem that only if a seed falls very close to a host plant could the seedling become established. But the situation is not as desperate as it appears. Dodder seedlings are able to “forage” for host plants! After germination, a seedling immediately sets off in search of a suitable host. If it “smells” one nearby, it adjusts its growth accordingly.

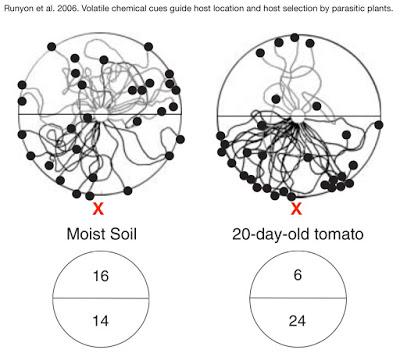

Justin Runyon and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that given the opportunity, seedlings of five-angled dodder grow toward their favorite hosts, tomato plants. Using 30 seedlings, the researchers put the basal end of each in a vial of water in the center of a paper disc 9 cm in diameter, with a tomato plant at the edge of the disc. Over four days, they marked on the paper disc the seedling's path of growth (diagrams below are composites for 30 seedlings). For comparison (i.e., a control), they did the same for 30 more seedlings but using pots with just moist soil—no plants.

X marks positions of “targets”: control pot with only moist soil, and pot with tomato plant.

The results were convincing: 80% of dodder seedlings with a tomato plant nearby grew toward the plant, and fairly directly. Those with only a pot of soil wandered more, and were evenly distributed between semicircles (3). The researchers then repeated the experiment using chemical extracts instead of entire plants, and got similar results—73% of seedlings grew toward the tomato-plant extract, and with less wandering. Thus directed growth was specifically in response to volatile chemicals released by the tomato plants (vs. light or color or something else). In other words, a dodder seedling follows its nose (4).Five-angled dodder also parasitizes wheat, but it prefers tomatoes if given a choice. When Runyon and colleagues isolated the various chemicals in the volatile extracts, they found out why. In addition to several appealing chemicals, wheat contains one that dodder finds disgusting. Tomatoes have no such defense.

Desperate Love Vine approaches its victim.

Notes

(1) Dodder can cause significant damage to crops, and is on the USDA Top Ten Weeds List. Eradication is difficult to impossible. Rarely can dodder be eliminated without also harming the host plant. Instead, it’s recommended that the host be removed, and a different crop planted. See Dodder (Cuscuta spp.) Biology and Management.

(2) Some reputable sources say a dodder seedling produces an anchoring root, which dies once a host is found. Sources also differ on survival time for unattached seedlings; they might survive for as long as a week. Perhaps these features vary with species. Cuscuta pentandra seedlings can grow just a few centimeters on their own, but even so, in a field of tomatoes or wheat, plenty of seedlings will find a host.

(3) Runyon and colleagues also did these experiments with paper discs divided into quadrants rather than two semi-circles, and obtained similar results.

(4) In their supplementary materials, Runyon et al. provide a very cool movie of a wandering dodder seedling searching for and finding a host! Click on “Movie 1” to download.

Sources

Kaiser, B., et al. 2015. Parasitic plants of the genus Cuscuta and their interaction with susceptible and resistant host plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 6: 45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25699071

Runyon, JB, Mescher, MC, and De Moraes, CM. 2006. Volatile chemical cues guide host location and host selection by parasitic plants. Science 313: 1964-1967. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17008532