By: Carol Linnitt

Cross Posted from: Vancouver Observer

According to an internal memorandum obtained by Postmedia’s Mike De Souza, the tailings ponds holding billions of litres of tar sands waste are leaking into Alberta’s groundwater.

The document, released through Access to Information legislation, confirms groundwater toxins related to bitumen mining and upgrading are seeping from tailings ponds and are not naturally occurring as government and industry have previously stated.

“The studies have, for the first time, detected potentially harmful, mining-related organic acid contaminants in groundwater outside a long-established out-of-pit tailings pond,” the memo reads. “This finding is consistent with publicly available technical reports of seepage (both projected in theory, and detected in practice).”

This newly released document shows the federal government has been aware of the problem since June 2012, without publicly addressing the information. The study, made available online by Natural Resources Canada in December 2012, was still “pending release” at the time Minister Oliver was briefed of its contents in June.

The study in question, co-authored by 19 scientists from both provincial and federal bodies including Natural Resources Canada, Environment Canada, the Geological Survey of Canada, was designed to distinguish naturally-occurring chemical substances from mining-related contaminants.

Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) spokesman Travis Davies told Postmedia’s De Souza the study’s evidence of chemical seepage into groundwater did not come as a surprise.

“Their study isn’t new in any way other than perhaps the laboratory methods and detection limits,” Davies said.

“We also know and report on the chemistry of groundwater from our monitoring wells that surround tailings facilities. So again, (there’s) no surprise.”

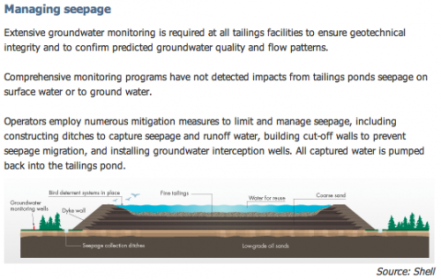

CAPP’s website acknowledges “seepage into ground water can occur,” while still claiming that “comprehensive monitoring programs have not detected impacts from tailings ponds seepage on surface water or to ground water.”

Shell’s weak explanation of how the tailing ponds will retain their contents.

In early 2012, a team from desmogblog.com traveled to Fort McMurray to document the growing impact tar sands expansion is having on the local landscape and wildlife. According to CAPP, existing tailings ponds cover 176 square kilometres (or 67 square miles) of land in the Fort McMurray region and are expected to grow.

Fort McMurray’s temporary tailings ponds currently hold billions of gallons of water, sand, clay, hydrocarbons, naphthenic acids, salt and other byproducts of the bitumen extraction and upgrading process. Even in negative 30 degree Celsius, the hot waste sends a plume of steam into the frozen air, a sign of the high energy costs of tar sands oil production.

An aerial view of one tailings pond shows the extent of the impact accumulating tar sands waste has on the local landscape. How the local landscape will be remediated and restored to its preexisting condition is becoming one of the tar sands industry’s most pressing long-term concerns.

According to a recently released plan by CEMA, an industry-funded consultancy group, tar sands companies are considering transforming tailings ponds into ‘end pit lakes,’ meaning they will be left as permanent features in the transformed landscape. The success or failure of these permanent installations will not be known until decades after their construction.

Conservation specialist Carolyn Campbell with the Alberta Wilderness Association said, “the basic concern is that end pit lakes with tailings at the bottom will release toxins such as naphthenic acids from tailings into the environment, to the detriment of ecosystems generally. And so many end pit lakes have been approved on sheer faith rather than demonstrable results that it’s creating a potential huge environmental liability.”

Bitumen processing and upgrading facilities line the Athabasca River in Fort McMurray. In 2011 water usage for tar sands operations amounted to 158 million cubic meters, the vast majority of which (112 m3) was withdrawn from the Athabasca River.

In November 2012, Environment Canada scientists released a study that showed tar sands pollution is contaminating the landscape up to 100km away from central refineries.

Toxic pollutants, traveling through the air year-round, have been found in tributaries of the Athabasca River where they are believed to disrupt development of fish embryos.

According to a ministerial briefing notes, greenhouse gas emissions from tar sands operations are expected to make up 15 percent of Canada’s total emissions by 2020, up from 4 per cent in 2005.

In 2008, Environmental Defense estimated leakage from tar sands tailings ponds equals 11 million litres each day, according to industry figures.

At current rates the tar sands produce about 3.3 million barrels of oil per day. Approved projects will bring that figure past 5 million barrels in the near future and proposed project might see that number jump to 6.2 million by 2030.