I love Douglas fir for the little mice trying to hide inside the cones. Their tails and back feet stick out, making the cones distinctive and the trees easy to identify. Mature cones and mouse tails are a uniform rich brown, but in youth, they’re exquisitely multi-colored.

I love Douglas fir for the little mice trying to hide inside the cones. Their tails and back feet stick out, making the cones distinctive and the trees easy to identify. Mature cones and mouse tails are a uniform rich brown, but in youth, they’re exquisitely multi-colored.

Young Douglas fir cones vary from green to red to purple, with yellowish mouse tails.

Okay, they’re really bracts (insert) – evolutionarily modified leaves. There’s one below each cone scale.

Most conifer cones have small bracts hidden inside. In Douglas fir, they’re nicely exserted.

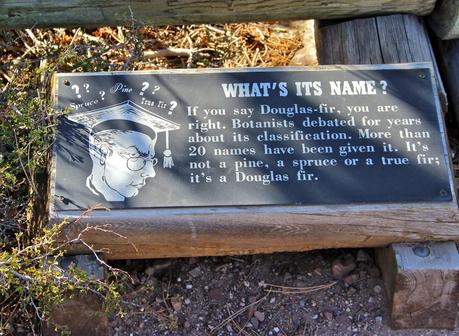

Botany instructors love Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) because it has at least twenty common names and therefore is a useful example of the superiority of scientific (Latin) names – each species has only one. [However if students pursue botany further, they’ll learn this isn’t always the case.] This tree of many names is most commonly called Douglas fir, or Doug fir among friends. But it’s not a fir. Some call it Douglas spruce or Oregon pine, but it’s neither a spruce nor a pine. The genus – Pseudotsuga – translates to “false hemlock” which is apt enough, as it also isn’t a hemlock.

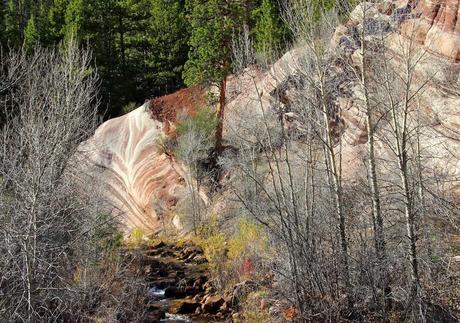

In mid-October I walked along Sheep Creek on the north side of the Uinta Mountains, through aspen and cottonwood trees bare of leaves, and vigorous young Douglas firs with straight trunks and symmetrical crowns loaded with cones. It was hard to believe this canyon bottom was devoid of vegetation just 50 years ago.

Young straight symmetrical Douglas fir.

Lots of trees had lots of cones.

Here's Sheep Creek – a picturesque gurgling brook the day I visited.

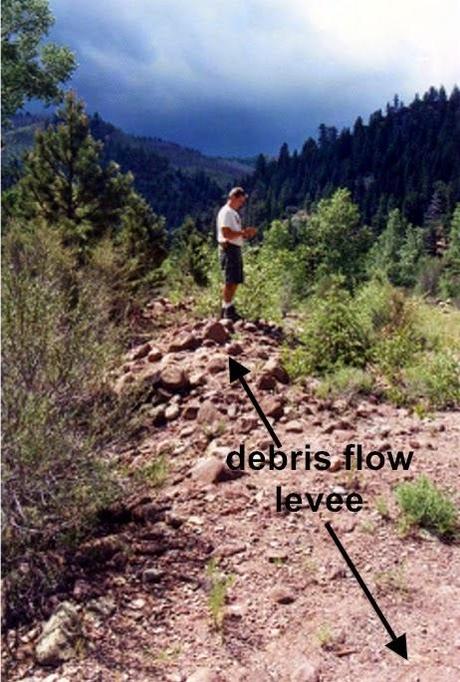

Sheep Creek normally is a small stream. But on the night of June 9, 1965, it turned into a deadly torrent of water, dirt and rock racing down the canyon. The weather the previous month had been cool and wet, and slopes probably were saturated. That may have been why an old landslide gave way, likely undercut by Sheep Creek. Tons of wet sediment slid into the stream, accelerating its flow. The surge probably traversed the mile to Palisades Campground in just a few minutes. It scoured the canyon bottom, picking up more debris – mud, silt, sand, gravel, boulders and vegetation (Sprinkel & others 2000). This scenario is in part conjecture because no witnesses survived. The seven people in the campground died when their vehicle was swept downstream with the debris.Whatever the cause and mechanism, it's clear that the debris flow devastated the canyon bottom. It destroyed five miles of road, three bridges and four camping areas, and left mud, rock and debris five feet deep in places. Debris flow levees – distinctive ridges with piles of boulders – are still visible 50 years later.

Looking down into Sheep Creek Canyon; temporary Douglas fir - aspen forest in foreground.

SourcesSprinkel, DA, Park, B and Stevens, M. 2000. Geologic road guide to Sheep Creek Canyon Geological Area, northeastern Utah, in Anderson, PB and Sprinkel, DA, eds., Geologic road, trail and lake guides to Utah's parks and monuments. UGA Publ 29. PDFUSDA NRCS. 2002. Plant fact sheet, Douglas fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii. PDF