Responsibility and Obligation

A huge thanks to Kati for being such a good sport throughout this whole ordeal. Above: The aftermath of what’s described below.

The thing about life is that shit happens. We take reasonable precautions, but shit still happens. It’s an old trope trotted out often in the comments section whenever rock climbing finds its way into the mainstream news outlets, but it’s always good to keep in mind that we ought to live maximally, lest we get caught in a freak tornado filled with sharks while playing it safe on the couch. I’d much rather be killed or maimed in a climbing accident than a car accident.

Highballs play for keeps. It’s part of what makes them so fun. The climber can achieve momentary mastery, being in control in an objectively dangerous situation. It feels good in an entirely personal way that must be experienced to be understood. It’s kind of a personal spiritual thing, although I’d be lying if I denied that a portion of my joy comes from getting away with something my parents wouldn’t really approve of if they knew what was going on out there in the woods.

I’ve sort of fallen in love with the Rockshop, a many-acre expanse of granite formations a mere 45 minutes from Lander. The chaotic jumbles contain endless hidden projects, their surfaces weathered by icy winter winds into a fine patina with brilliant texture. As with many locations, the most beautiful lines are a bit taller and more dangerous.

One fine day we had a big crew out there. Yadda yadda and we were on our way to a different boulder when Skyler says, “hey, we oughta check out Young Blood.” We says what is that? “It’s a V5 highball, it’s right on the trail to that other boulder we’re going to.”

A couple of us are more psyched to try harder rather than scarier, but then we go up and look at this thing and it’s, like, the tits. Fun 5.11- climbing to an obvious crux, a big angled rail forming a pinnacle with the arete, which you pinch with the left hand, make a big committing move around said arete to grab an oh-thank-you-Lord jug rail that you gloriously follow to the summit. The crowd will go wild. The moves were in the sun, but the adjacent boulder allowed us to stand up there and shade the topout.

We made a sea of Organic pads. The best pads in the business. And Alex and Skyler and I tried it and we all bailed before the big move out right. Spooky! But safe. We were jumping down on to almost a foot of foam.

So we shuffled all the pads to make it as safe as possible. The landing wasn’t what I’d call flat, rather, it had a pair of cavernous pits that could swallow a basketball, but we figured with two layers of full-sized pads in a four-square arrangement, with a blubber pad over all that, would keep us from punching through.

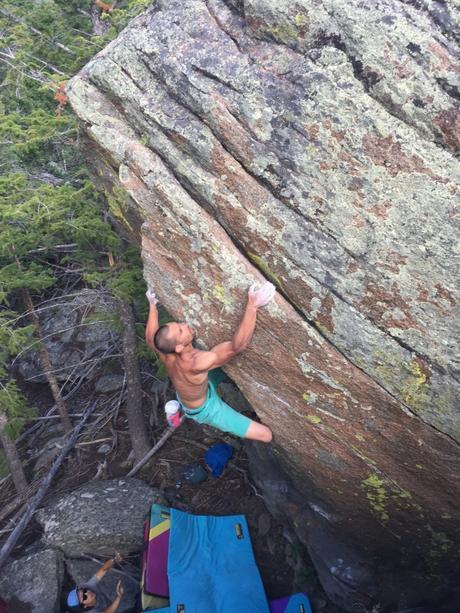

Alex sets up for the crux

Alex on the glory jugs, catching a piece of chalk to mark the good part of the crimp.

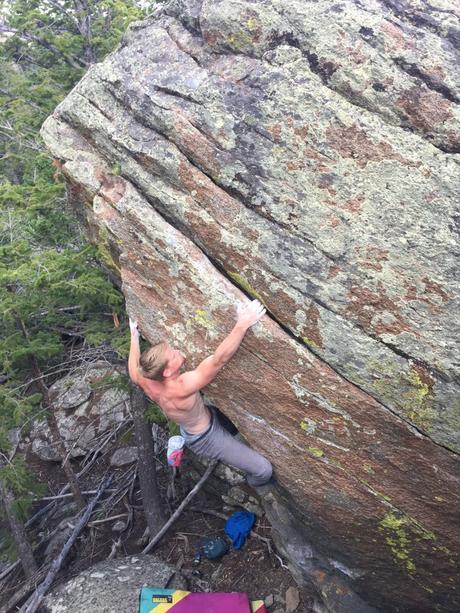

Glorious topout jugs.

Alex stepped up and fired it, put ticks and chalk to aid our passage, and myself and Skyler followed on consecutive goes. We all raved about it, like, man, that was so good! So satisfying to slap out right and snag the jug instead of barn-dooring off and flying backward with 14 feet between your climbing shoes and the pads. Skyler waxed poetic about the whole experience. The happiness quotient of our group was high.

My turn! I found the move to be a little less secure than I was hoping.

Skyler sends. Like a boss.

So Kati, who’d been sitting this one out, gets pretty psyched. We get psyched for her too. She can share in our euphoria, we can watch another badass ascent go down. The method is solid. She is strong. She easily gets through the long setup and grabs the good part of the left hand pinch, and does the exact same throw out right that I’d just witnessed twice before from my vantage as a spotter. Except she didn’t fall into the jug, she fell off the boulder.

Suddenly she was coming at me, feet slightly behind her and her body doing a half-corkscrew before she landed on her feet right on the pads. But near the edge. And her force carried her through an extra foot and a half into one of the pits. She leapt up onto her knees and immediately tugged her climbing shoes off, cursing in a way that indicates panic.

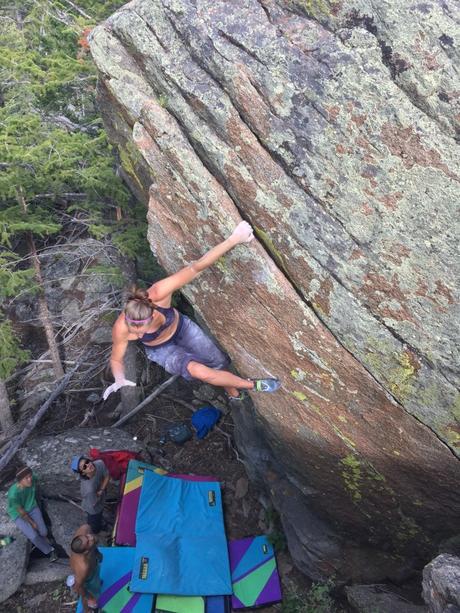

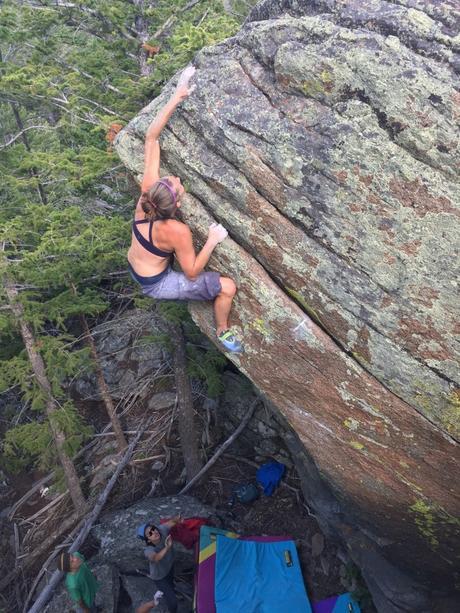

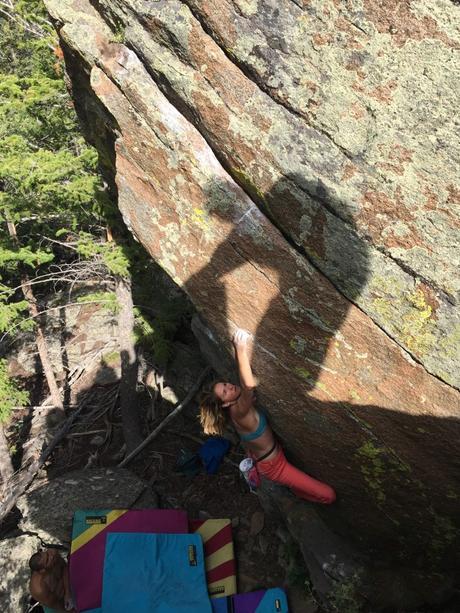

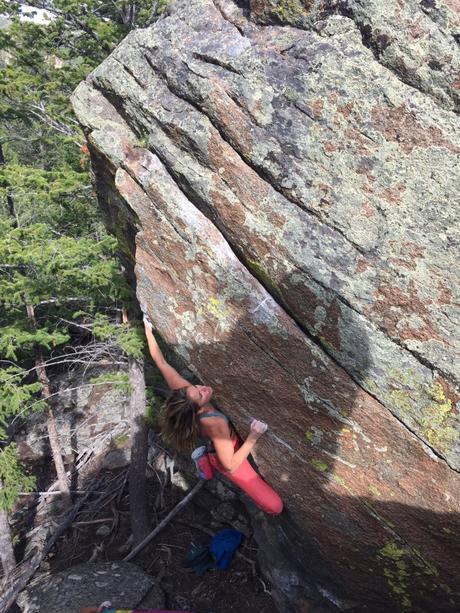

Kati looking solid

Kati eyes the prize

Oh shit….(but damn, look at that hair!)

A Sherpa’s job is never easy.

I don’t often use my heart in metaphors, but it’s most apt in this case: my heart absolutely sank. I pride myself on being a good spotter, on studying the craft fastidiously. I’m inspired by 5-star spotters, like Joel Ruscher, Nuno Monteiro, and most people who climbed before crash pads. To me it’s like belaying: not only is it harder than most people think, but it’s the most important skill in its discipline. Eyes on the center of gravity, not the next hold. Protect the head and spine above all, keep the climber on the pads, keep the hands in lobster claws.

The spotters are obliged to do everything in their power to prevent injury, but shit happens. As such, safety is ultimately the climber’s responsibility. We all understand that climbing is dangerous, that we can get seriously injured if something goes wrong. We back off of things that don’t feel right, no matter what our spotters or belayers say. Above all, we understand that the decision to leave the ground is 100% personal, and we must accept the consequences.

Of course, none of this talk of personal responsibility makes it any less shitty when your friend has just broken an ankle, and you were the person obligated to do your best to prevent just that.

We breathe deeply and assess the situation. Kian is not thrilled at this moment. Kati probably isn’t either.

What’s brown and sticky and taped to Kati’s leg?

Alex: I’m going to have to be this girl’s servant. Shit. Kati: I‘m dependent upon Alex. Shit.

Our crew was a good one. Alex did her best to calm Kati down, while the rest of the crew got water, Aleve, warm clothes, and tape. I lashed a couple of sticks to Kati’s leg to keep her ankle from deviating any further. We decided that once we got back to the main trail, Skyler and I would tandem-carry her the 1/4 mile back to the car, while the rest of the gear got divvied up between the rest of the crew.

As I gave Kati a piggy-back down to the main trail, I told her I’d be thinking about this one for a long time, probably forever. What could we have done differently? What could I have done to prevent the injury? Being the sweetheart she is, Kati assured me I had no guilt, that it was entirely her fault, that it was shit luck, etc. Still, I know there are lessons to be learned here.

I reviewed my own role in spotting. I should’ve noticed that when Skyler went for the final move, his hips recoiled a lot, indicating that he would’ve come pretty far back if he’d missed the jug. We should’ve moved the pads back a bit further. Furthermore, it would’ve been easy to move the pads that protected the beginning of the climb back to protect the end.

When Kati was in the air, all I saw were her feet headed straight for me. Trying to do too much in this situation could easily result in her flipping upside-down…Speaking at least for myself, I would much rather land on my own from that height than have someone try to “catch” me in any way. We’re both more likely to get hurt than if I just hit the ground feet-first and crumple. The worst is when spotters try to do too much and the falling climber has to quickly react to a new balance and trajectory. So when Kati came down, I carefully followed her center of mass and grabbed her hips to ensure she’d come down on the pads and not rotate backward. Trying to slow her downward momentum in this situation would’ve been next to impossible, since she was falling leaning slightly toward the boulder and away from me. Had I shoved her in any way, she would’ve hit the ground with the same force, but now with a horizontal vector added to her overall movement (you can add a sideways velocity vector but can’t reduce the vertical velocity in this situation). She could’ve also smacked her face or hurt a shoulder/elbow in trying to protect her face from hitting the pads. Basically, myself and the other spotters were unable to slow her fall at all.

In terms of preventing the accident, we could have done 2 main things. The first would’ve been to fix the landing and make it flat. We ended up doing this the very next day we went to the boulder. The second would’ve been to spot with an additional floating pad. But, as with most accidents, we got complacent.

I later learned that Kati’s is at least the third ankle claimed by a fall from Young Blood. Clearly, this problem is a sought-after highball, and we felt it better to flatten out the landing instead of waiting to hear of more injuries. It seemed the big pit was right in the fall zone. Hopefully, the new landing will reduce the number of accidents in the future.

This was a few weeks ago, and we just saw Kati in her wheelchair at the Outdoor Retailer show. She’s in good spirits, at least as good as can be expected, and I know she’s a trooper who, with the help of her roommate Alex, will bounce back with a fury. And if there’s one last lesson to be gained from this whole experience, it’s this: Health insurance! Fixing a medial malleolus costs an order of magnitude more than every piece of climbing gear you’ve ever bought, combined.