Just a few days after starting its own COVID-19 vaccination program , India provided vaccines as grant- in-aid to other countries1 . This was in sharp contrast to some high-income countries which stockpile vaccines, and block proposals to suspend intellectual property rights in World Trade Organisation2. India now is in the midst of a humanitarian crisis 3 but its vaccination rates continue to fall. While it is not possible to go back in time and make amends to ensure availability for all, revising the current vaccination strategy (which is riddled with equity issues) can save lives , prevent health systems burdening and ensuring a functioning ecosystem during the pandemic .

Equity enables maximizing benefits from scarce resources

India’s original vaccination strategy was to sequentially vaccinate priority groups healthcare workers, frontline workers, people more than 50 years. of age and younger people with associated comorbid conditions (diabetes, hypertension, cancer, lung diseases) 4. In principle this invoked equity – prioritising those at highest risk. However, the Indian government continually changed its strategy – announcing more inclusive eligibility criteria for vaccination every month. The last of these came suddenly in the last week of April 2021, when the Indian government announced a new “liberal policy” for vaccination5.In midst of the current crisis, while already being riddled with shortages the new policy announced that everyone above 18 years will be eligible, and effectively removed any distribution or price controls for manufacturers. This is unparalleled – no other federal democracy is making citizens pay for COVID-19 vaccines or have states competing to secure supplies. The huge demand amid all the death and despair in th current wave meant that the two Indian vaccine manufactures resorted to differential and predatory pricing. They fixed prices for state governments which are almost twice of the price paid by the union government ; it is four times for private hospital 6. An immediate consequence of this was that most state governments were not able to offer vaccines for high-risk groups , while even richer people(who can pay ₹ 1600-2400 , £ 15 to £ 25) in non-priority 18-45 years age group are able to access vaccines from private hospitals 7. The “liberal policy” also perpetuates regional inequities, wherein richer state governments will be able to buy more doses for non-priority groups while poorer states (with weaker health system) will have to wait for revenues to accrue for buying vaccines for priority groups.

The realities of vaccine shortage need to first publicly acknowledged, and a pragmatic and equity-based strategy needs to be adopted. As per media reports, only 37% of frontline and health workers had been fully vaccinated by mid-April 8 .

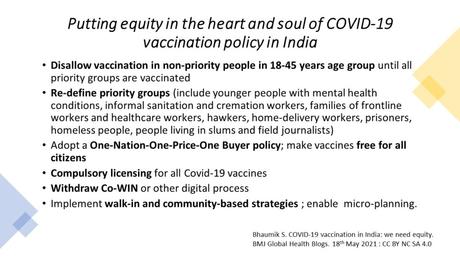

India needs to prioritise people “who matter and are in need” over the “rich and elite”. Vaccination of non-priority people in 18-45 years of age, should be stopped until adequate coverage of priority groups is acquired. A moral, social, and human rights lens is essential for the purpose. Younger people with mental health conditions, informal sanitation and cremation workers, families of frontline workers and healthcare workers, hawkers, home-delivery workers, prisoners , homeless people, people living in slums and field journalists who are at higher risk 9 10 11 need to be under priority groups. Some of the re-defining of priority groups has been done by states like West Bengal and Delhi – but this is not uniform across the country.

Adopting a “One Nation – One Price – One Vaccine Buyer” policy such that the Government of India buys and makes it free for all citizens of India is the need for the hour. To overcome shortage, it can issue compulsory licenses (under Section 92 of the Indian Patent Act for public health emergencies) for all COVID-19 vaccines. A single buyer and a fixed price of ₹ 150 (£ 1.5 ; current price paid by the Union government) for the entire nation would prevent pandemic profiteering.

Digital health driven inequity

Vaccination in India require pre-registration through a centralized online digital system called Co-WIN. With only 20% of Indians using internet12 the implementation strategy is not in touch with ground realities. The “digital divide” is even greater in rural areas, particularly in women, tribal/Adivasi people, and the urban poor13 who remain clueless about the system. Urban youth are traveling to rural areas to get vaccines14 –potentially transmitting COVID-19 to villages. Micro-planning 15 and participatory community engagement16 is crucial for successful implementation. India has in the past used them successfully without any digital tools. The Co-WIN based registration and tracking system needs to be stop and time-tested walk-in and community outreach (for disabled, homeless, very old people and other equity groups) needs to be adopted.

Instead of investing in digital health, government needs to invest in employing more vaccinators and vaccination officers. The current strategy of drawing into existing human resources has led to disruptions in routine service delivery 17 18 .

The way forward

Mahatma Gandhi’s maxim that a “nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members” should guide the overhauling of the COVID-19 vaccination policy. Getting the vaccination program right in India is crucial for the pandemic endgame too. There is not a moment to waste.

About the Author

Dr Soumyadeep Bhaumik is a medical doctor and international public health specialist working in The George Institute for Global Health India. He is also associate editor of BMJ Global Health. Views are personal and not necessarily reflective of employer or the BMJ Global Health. He tweets at @DrSoumyadeepB

Competing interests: I have read the BMJ Group Conflict of Interests and declare no competing interests.

Funding : None

Acknowledgment : Dr Sambit Dash from Melaka Manipal Medical College, India with whom author had a discussion.

Provenance : The article is not peer-reviewed.

The article was originally published in BMJ GH Blogs and is published here under CC-BY-NC-SA

References

- Ministry of External Affairs. Made-in-India COVID19 vaccine supplies so far (In lakhs): Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India; 2021 [Available from: https://www.mea.gov.in/vaccine-supply.htm accessed 02 May 2021.

- Sachs JD, Karim SA, Aknin L, et al. Priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic at the start of 2021: statement of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission. The Lancet 2021

- Thiagarajan K. Why is India having a covid-19 surge? BMJ 2021;373:n1124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1124

- MOHFW-GOI. COVID-19 vaccines : operational guidelines New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2020 [Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/COVID19VaccineOG111Chapter16.pdf.

- Sahu P. New ‘liberal’ policy: States to spend a tidy sum for vaccination drive: Financial Express; 2021 [Available from: https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/new-liberal-policy-states-to-spend-a-tidy-sum-for-vaccination-drive/2237743/ accessed 17th May 2021.

- Mahal J. ‘Don’t Leave Vaccine Pricing And Distribution To Manufactures’: Supreme Court Questions Centre’s COVID Vaccination Policy 2021 [cited 2021 03 May]. Available from: https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-questions-centres-vaccine-policy-vaccine-pricing-and-distributionto-manufactures-173389.

- FE Online. COVID-19: Amid vaccine shortages across India, big private hospitals start vaccination for 18-44 years: Financial Express; 2021 [cited 2021 03 May]. Available from: https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/health/covid-19-amid-vaccine-shortages-across-india-big-private-hospitals-start-vaccination-for-18-44-years/2243577/.

- Dey S. Only 37% of 3 crore health, frontline workers fully vaccinated New Delhi: Times of India; 2021 [Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/only-37-of-3-crore-health-frontline-workers-fully-vaccinated/articleshow/82135322.cms accessed 19 April 2021.

- Nemani K, Li C, Olfson M, et al. Association of Psychiatric Disorders With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78(4):380-86. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4442 [published Online First: 2021/01/28]

- Akiyama MJ, Spaulding AC, Rich JD. Flattening the Curve for Incarcerated Populations – Covid-19 in Jails and Prisons. N Engl J Med 2020;382(22):2075-77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005687 [published Online First: 2020/04/03]

- Tan LF, Chua JW. Protecting the Homeless During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Chest 2020;158(4):1341-42. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.577 [published Online First: 2020/06/13]

- World Bank. Individuals using the internet ( % of population) – India Washington: World Bank; 2021 [Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=IN accessed 03 May 2021.

- Bose A. Explained: Why Delhi’s Slum Dwellers Are Struggling To Get Vaccinated Delhi: Boom Live; 2021 [Available from: https://www.boomlive.in/explainers/why-delhis-slum-dwellers-are-struggling-to-get-vaccinated-13164 accessed 18 May 2021.

- Lalwani V. Tech savvy Indians drive to villages for Covid-19 vaccinations. Those without smartphones lose out: Scroll 2021 [Available from: https://scroll.in/article/994871/tech-savvy-indians-drive-to-villages-for-covid-19-vaccinations-those-without-smartphones-lose-out accessed 18 May 2021.

- Mallik S, Mandal PK, Ghosh P, et al. Mass Measles Vaccination Campaign in Aila Cyclone-Affected Areas of West Bengal, India: An In-depth Analysis and Experiences. Iran J Med Sci 2011;36(4):300-5. [published Online First: 2012/11/02]

- Burgess RA, Osborne RH, Yongabi KA, et al. The COVID-19 vaccines rush: participatory community engagement matters more than ever. Lancet 2021;397(10268):8-10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32642-8 [published Online First: 2020/12/15]

- Chatterjee P. India’s child malnutrition story worsens. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 2021;5(5):319-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00064-X

- Shet A, Dhaliwal B, Banerjee P, et al. COVID-19-related disruptions to routine vaccination services in India: perspectives from pediatricians. MedXRiv 2021; [pre-print]