As the COVID-19 pandemic blazes through North America and Europe, the case counts from Africa remain quite low. The Worldometers website indicates that South Africa leads the tally with 15,515 cases, followed by Egypt (12,229 cases) and Algeria (7,019 cases). Overall, the African continent has reported 86,683 cases, 2,785 deaths. This indicates an Infection Fatality Rate of 3.21% (95% confidence interval: 3.09% to 3.33%). With 33,521 recoveries, the infection recovery rate stands at an impressive 38.67% (95% CI: 38.35% to 39.00%). As far as testing is concerned, South Africa leads the tally with 460,873 tests (7,783 tests per million population), with a testing rate of almost 30 tests per detected case. It is followed by Ghana, where 173,096 tests have been done, (5,586 tests per million population), and a testing rate of a bit over 30 tests per detected case. Mortality tally is led by Egypt, which has reported 630 deaths, representing 22.62% (95% CI: 21.09% to 24.23%) of all deaths reported from Africa due to COVID-19 (n=2,785). Population based infection rate is the highest in Djibouti, which has registered 1,401 cases, and with a population of about 1 million, represents an infection rate of 1,421 cases per million population.

In comparison, the United States, which has recently emerged as the hotspot driving the global tally of cases, has registered over 1.5 million cases, almost 91,000 deaths, an infection fatality rate of 5.96% (95% CI: 5.92% to 6.0%), infection recovery rate of 22.67% (95% CI: 22.6% to 22.74%); it has conducted almost 12 million tests, at the rate of 35,903 tests per million population, at a testing rate of almost 8 tests per detected case.

While the numbers from Africa seem really positive, it has also fueled the conjectures that there is an association between temperature and caseloads - a hypothesis which is rapidly losing favor both with the scientific and the general media as the burden of cases continue to rise in tropical countries with improving testing rates. A recent New York Times article highlights the fact that rather than a slow epidemic, massive detection bias is perhaps the reason for the low reporting of cases. Drawing on the examples from Kano, Nigeria and Mogadishu, Somalia, the article states:

"But blazing hot spots are beginning to emerge. Kano is only one of several places in Africa where a relatively low official case count bears no resemblance to what health workers and residents say they are seeing on the ground. In Somalia's capital, Mogadishu, officials say that burials have tripled. In Tanzania, after cases suddenly rose and the United States Embassy issued a health alert, the Tanzanian government abruptly stopped releasing its data. In Nigeria, some say that with the outbreak in Kano so widespread, the city may already be home to a giant, unintentional experiment in herd immunity."

Covid-19 Outbreak in Nigeria Is Just One of Africa's Alarming Hot Spots. New York Times.

Whilst the ongoing responses are getting ramped up, the New York Times piece highlights four concerning aspects of the epidemic, which could perhaps be as dangerous as a falsely low count of cases (bold mine):

- Excess Mortality: "One doctor said the department's death registers for April showed far more patients had died than normal. Most patients were sent home, he said, and the hospital's staff members often would hear later that they had died."

- Delay in getting test results: "Nigeria, a country of about 200 million people, says it can in theory do 2,500 tests a day, and Kano up to 500. But it has been conducting far fewer tests, typically 1,000 to 1,200 daily. Test results in Kano can take two weeks. Doctors awaiting their test results cannot go to work. People in quarantine cannot leave."

- Lack of PPEs and subsequent infections in healthcare workers: "With no personal protective equipment except surgical masks, the doctors said they knew the risks they were running in treating these patients. They said that they begged the hospital management for N-95 masks, face shields, gloves and aprons, but that none came. They asked for an isolation center at the hospital, scared that patients with other ailments would be infected. They wanted the facilities fumigated. Nothing happened."

- Adverse behavioral patterns discouraging adherence to social/physical distancing norms: "Many in the city think the coronavirus is a hoax, perhaps because public messaging about it is mostly in English, which most Kano residents do not speak, health experts said. Others believe that a Covid-19 diagnosis is a death sentence, the experts said, and do not want their neighbors to think they are infected. So they avoid being tested, and try to behave as if all is normal. They go to burials, and shake fellow mourners' hands because it would be socially unacceptable not to. They shop, barefaced, in crowded markets. They hold soccer tournaments - a recent one was called the "Coronavirus Cup.""

As more accurate tests, which are cheaper to deploy, have better sensitivity and specificity, and are less technically demanding become available, it is hoped that public pressure and demand for testing for COVID-19 will lead to ramping up of the testing in African countries. If this does indeed happen, it will be interesting to see whether newer patterns emerge. Many African nations are perhaps not testing as much as they could, but of those which are (South Africa, for example), their infection detection rate, fatality and other indicators are broadly in line with the situation seen in countries with slower, smoldering spread of the epidemic of COVID-19. As case counts continue to mount in tropical countries with similar socioeconomic profiles and infectious disease burden, it remains to be seen if improved testing rates will lead to a change in the trajectory of the epidemic curve in Africa.

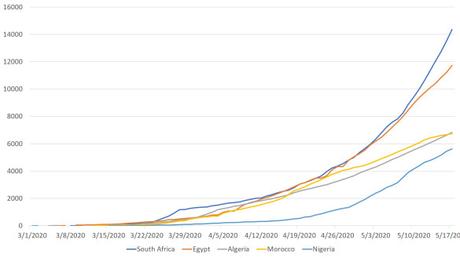

Epidemic Curves of 5 African Countries with Highest Case Counts Reported

Epidemic Curves of 5 African Countries with Highest Case Counts Reported