Applying the concept of consent to all relationships in various ways.

Content warning: abusive relationships and abusive sex are touched on briefly in this post.

Recently I wrote a post here about open relationships. It explored how the concept of openness might be applied to relationships more widely than just open non-monogamy – which is what people usually mean when they talk about open relationships. Whilst my research with polyamorous communities started by focusing on non-monogamy, I think that openness is a useful concept to apply to all kinds of relationships, not just non-monogamous relationships or just partner relationships.

A similar thing has happened with my research on kink, or BDSM, communities. Initially, like many of the researchers who have tried to learn from – rather than explain – kink, my focus was on the ways in which people ensured that their play was Safe, Sane and Consensual (SSC) or Risk Aware Consensual Kink (RACK). Those terms are the mantras of the kink communities. Whilst RACK recognises the problems with the idea that the things people do could ever be entirely safe, or completely sane (whatever that means), it retains the idea that consent is the vital cornerstone of BDSM sex.

However, my latest piece of research with kink communities was all about how common ideas about consent are currently being questioned, and reconsidered, by people in those communities. Online conversations over the last three or four years have radically challenged understandings of consent in ways that I think are useful for everyone, far beyond just kink communities.

The Consent Culture movement has argued that the idea of consent needs to be expanded out in a number of ways.

Consent is about:

- All sex, not just kinky sex

- Enthusiastic mutual agreement, not just the ability to say ‘no’

- The whole relationship, not just the sex parts

- All relationships, not just sexual relationships (including the relationships that we have with ourselves)

- The whole culture, not just the individuals within it

The idea is that unless we aim for consensual relationships beyond the bedroom, with all the people in our lives, and in our wider culture, it will be very hard – if not impossible – to ensure consent within sexual encounters, whether those are kinky or non-kinky. It isn’t possible to isolate just one aspect of human behavior (sex) and ensure that it is conducted under a completely different set of rules than the ones that we use when managing the domestic chores,for example, or inviting someone out to a social occasion, or putting structures in place for how our work projects will be conducted.

I’ll take each one of these expansions in turn now, and explore how we might encourage all of our relationships, networks and communities to become more consensual.

All sex, not just kinky sex

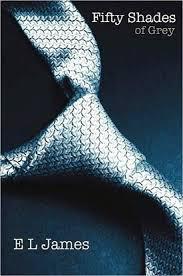

This last few months my main research project has involved analysing sex advice media. One thing that is really noticeable in mainstream sex advice is that there is hardly any consideration of consent at all. On the few occasions when consent is mentioned, it only happens when the authors start writing about kinky sex. In all of the books listing multiple positions for sex, and all of the agony aunt musings on sexual problems, there is hardly any mention of the need for sex to be consensual, or of the role of lack of consent in sexual difficulties. But when the topic of kink comes up – as it increasingly does since the 50 Shades phenomenon – suddenly everyone is being advised to proceed very carefully and to ensure that they have a safeword.

Of course it is good to see consent being mentioned at all, but given the extent to which non-consensual sex happens in non-kinky forms of sex it is shocking that there is so little about how to engage in that kind of sex consensually. It often seems like consent is just being used, in these few kinky mentions, to remind readers that BDSM is something ‘different’ and riskier: so it is seen as requiring consent in a way that ‘normal’ sex doesn’t.

In the sex advice book that Justin Hancock and I are planning, we aim to weave consent throughout the book rather than considering it only in relation to certain kinds of activities.

Enthusiastic mutual agreement, not just the ability to say ‘no’

One of the first things that many of the BDSM blogs say is that we need to move away from the ‘no means no’ version of consent, which is the one that we generally hear about. ‘No means no’ is the idea that sex is consensual so long as the other person doesn’t refuse our sexual invitation, or actively say ‘no’ (or use a safeword) during sex.

The idea of ‘enthusiastic’ or ‘yes means yes’ consent is that ‘no means no’ is a pretty poor basis on which to proceed.

For one thing, studies have found that people very rarely use the word ‘no’ when refusing things. It can be very difficult to start using it in a sexual context given how unfamiliar it is. Researchers asked young women and men how they would tend to turn down a friend’s invitation to go to the pub if they didn’t want to go. Generally they reported that they would say something like ‘I’m sorry I’m busy tonight’, or ‘I’ve got to finish this project’. Similarly, when they were asked what they’d do if they went home with somebody but then decided that they didn’t want sex, people of all genders said that they would say something like ‘I’m so sorry I’m actually really tired’ or ‘I’ve realised I’m not ready for this’. Crucially all the participants were clear that they would recognize such statements – from another person – as meaning the exact same thing as ‘no’.

This kind of finding lies behind the enthusiastic consent idea that we should read anything other than an enthusiastic ‘yes’ as a ‘no’. As one website puts it:

- “NO” means NO.

- “Not now” means NO.

- “Maybe later” means NO.

- “I have a boy/girlfriend” means NO.

- “No thanks” means NO.

- “You’re not my type” means NO.

- “*#^+ Off!” means NO.

- “I’d rather be alone right now” means NO.

- “Don’t touch me” means NO.

- “I really like you but …” means NO.

- “Let’s just go to sleep” means NO.

- “I’m not sure” means NO.

- “You’ve/I’ve been drinking” means NO.

- SILENCE means NO.

- “__________ ” means NO.

Research suggests that the kind of ‘miscommunication’ that is often cited by perpetrators when non-consensual sex happens is generally not valid. People are mostly very capable of understanding a refusal that doesn’t include a ‘no’ in both social and sexual situations, and a direct ‘no’ is actually relatively uncommon.

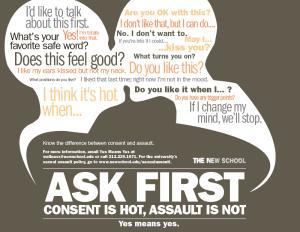

However, there are certainly differences between people, particularly in terms of culture, class and neurodiversity, which meant that one person might struggle to read another’s reluctance. For this reason, enthusiastic consent can be a more helpful model than ‘no means no’ because it suggests that people only go ahead if everyone involved is enthusiastically saying – or demonstrating – that they want to do so. If you’re not receiving a clear, wholehearted, enthusiastic message to go ahead from a partner you don’t go ahead, and you check in with them (and vice versa). Also this is an ongoing process throughout the whole encounter, rather than a one-off thing that you do only at the beginning.

However, as with the capacity to decline sex, the capacity to enthusiastically consent is constrained by a number of other factors, so it is important not to leave it there. The Consent Culture bloggers suggest many things that individuals and communities can do in order to put in place the best possible conditions for people to engage with each other consensually.

The whole relationship, not just the sex parts

Here we can return to 50 Shades of Grey, as a helpful example. In the novels (and presumably the upcoming movie), it could be argued that the sex/kink was relatively consensual, at least according to the ‘no means no’ version of consent. Christian presents Ana with a list of all the things he likes and doesn’t like sexually, and she is able to remove anything that she doesn’t fancy doing. He also introduces her to the concept of a safeword so that she can stop a scene at any point.

Of course the enthusiastic consent model would prefer it if they mutually came up with a list of things that they both actually wanted to try, which they revised over time. Also it would be good if they considered how they might both check in with each other (verbally and/or non-verbally) throughout what they were doing to ensure they were still on the same page, and perhaps if they talked more together about how they both tended to express things so they would know that going in.

But the biggest problem with the consent between Ana and Christian is that it doesn’t exist in the rest of the relationship, only in relation to sex. Christian never hears Ana’s clear ‘no’ about him buying her gifts, following her on holiday, and getting involved in her work. Also both characters continually attempt to pressure, persuade or cajole the other into being what they want them to be: a submissive in Ana’s case, and a loving husband in Christian’s case. This is despite both stating very clearly that this is not what they want, several times over.

Could Ana really trust that Christian would respect her ‘no’ or safeword during sex when he had so often ignored it at other times? Could Christian really trust Ana’s consent to engage in activities when he knew that she was so desperate to convince him into the kind of relationship that she wanted with him.

So we can usefully ask ourselves how possible consent is in one aspect of a relationship (such as sex) if it is absent in other areas. If we find ourselves trying to force, control, pressure, persuade, or manipulate our partner in some areas, how easy will it be for us to adopt a different approach, or for them to be able to clearly express enthusiasm, or refusal, in others?

This is not easy stuff. We live in a wider culture of relationships where it is often deemed acceptable to try to gently – or not so gently – change a partner to be more like we want them to be: to nag them or niggle at them or pressure them to alter things because it would be better for us, or because we think it would be better for them. It can be easy, when we know someone well, to subtly manipulate them into doing what we want at the weekend, or to pressure them into going on the kind of holiday that will make us happy, or to try to convince them to dress differently or go on a diet, for example.

A particularly pervasive myth in relationships is that it isn’t acceptable to change. ‘You’ve changed’ is often deployed as an insult. This has implications for sex where people can feel huge pressure to continue the frequency and type of sex they had at the start. This can make it virtually impossible for them to feel able to refuse sex of particular kinds, or to express (or even know) what they might be enthusiastic about.

All relationships, not just sexual relationships

Several of the Consent Culture bloggers point out another difficulty in cultivating the kind of consensual relationships that are necessary in order for sex to be consensual. This is the fact that so few other relationships in our lives are consensual. As The Pervocracy puts it:

I think part of the reason we have trouble drawing the line “it’s not okay to force someone into sexual activity” is that in many ways, forcing people to do things is part of our culture in general. Cut that shit out of your life. If someone doesn’t want to go to a party, try a new food, get up and dance, make small talk at the lunchtable – that’s their right. Stop the “aww c’mon” and “just this once” and the games where you playfully force someone to play along. Accept that no means no – all the time.

Our interpersonal relationships are shot full of non-consent on this micro level. And, again, the model is often one of ‘no means no’ rather than of enthusiastic consent. Even though we know full well that somebody’s reluctance, or claim to be busy, or going quiet , or changing the subject, means that they don’t want to do what we’ve asked, it is easy to pretend that they might still be open to it because they haven’t actually said the word ‘no’.

Attempting to shift to an enthusiastic consent model in all our relationships can be very liberating. For example, after lots of conversations about this kind of thing in my friendship groups, I’ve noticed a subtle shift from a default assumption that if you’ve said you’re going to an event you ought to go. Instead now the default assumption is generally that we all have times when we get to the time of the event and –for whatever reason – we’re not in the right place for it. It is totally fine to say that we’re not up for it under those circumstances, without the need to provide any kind of explanation, and with an implicit ban on any attempts to persuade somebody further.

I’ve realised how much more enjoyable it is to have a coffee with somebody, or an evening out, when I know that the only people present are people who actively want to be there. It’s also a relief to know that it is totally fine to reschedule or to opt out when I’m not in the mood.

Enthusiastic consent in all relationships might involve things like: checking whether somebody wants physical contact rather than assuming (e.g. would you like a hug?); remembering to check in with people when there is an ongoing arrangement between you that whatever you’re doing is still something that they enjoy; assuming that the lack of an enthusiastic ‘yes’ to an invitation means the person probably doesn’t want to do what you’re suggesting, and leaving the ball in their court instead of continuing the invitations.

It’s also important to remember that different things work for different people. So in any relationship it could be valuable to initiate a conversation about how you can best communicate in order that the other person will feel able to decline, respecting that their way of communication might be different to yours. For example, they may find it easier to communicate about these things over certain media, or they could let you know that a certain response from them generally means that they are reluctant or uncomfortable.

Of course none of this is at all easy, especially when it runs so counter to the way we’ve often culturally learnt to do these things, and when we’ve often learnt to experience refusal as a personal rejection. But it is good to keep touching in with yourself about whether you are approaching people in a way that opens up, or closes down, their freedom to consent or not (e.g. to social arrangements, to work projects, or to the relationship in general).

(including the relationship that we have with ourselves)

This takes us to another major aspect of relationship consent which strangely only occurred to me very recently. I was talking about a recent interaction that I’d experienced as pushy and pressurising, suggesting that it felt non-consensual. A friend pointed out to me that I hadn’t been treating myself consensually in the situation.

I was shocked that I hadn’t noticed this given that I’m usually such a big advocate of the need for self-care and kindness as foundations for treating others compassionately. Looking back on the situation I realised that part of me felt obligated to respond in the way that I assumed the other person wanted me to. Then I felt trapped into a corner of either agreeing and feeling resentful, or refusing and feeling guilty and/or angry with them for putting me in that position. I realised that if I could treat myself consensually -really knowing that it was okay to agree or decline, and respecting my own limits in terms of what I could and couldn’t offer – then it all felt much less emotionally loaded and trapping.

Another situation which occurred to me was when I was at a social event. I didn’t want to talk with anyone because I was worried about getting pulled into a long conversation with somebody I didn’t really connect with. I realised that I was treating myself non-consensually in believing that once I’d started a conversation it wasn’t okay to move away. That meant I wasn’t engaging with anyone at all unless I could come up with a ‘good excuse’. An alternative would be to allow myself that it is fine to honestly say when I’ve got to the point that I just want to be alone, or with somebody I know well rather than in a group, or that I want to chat with a few different people over the course of the event.

Recently I had a realisation that, most evenings, I really enjoy doing something social early on (generally with one other person or with a small group), and then having some time at home before going to bed. I notice how I still don’t always feel okay just expressing that to friends who are more into late nights and who invite me along. Consensual self-relationships are definitely something that require cultivating!

Treating ourselves non-consensually can lead to us closing down because we fear the situations we might get into. For example, we might be worried that we will offer too much to somebody and have less time or energy for ourselves; that we will get into a relationships of whatever kind that doesn’t feel good for us because we think that it is what the other person wants; or that we won’t feel able to change what we have to offer as we (inevitably) change over time. This can lead to an all-or-nothing approach. On the other hand, when we are consensual with ourselves we can refuse; or offer only what we have to offer knowing that it is okay to change; or ask for time to consider things rather than responding straight away.

None of this is to say that such conversations or negotiations will be pain-free. But with a foundation of self-consent, the pain of acknowledging a discrepancy in what any two (or more) people want may become less enmeshed in a larger tangle of guilt, shame, anger, or self-recrimination. Hopefully you can stay with the loneliness that the other person doesn’t share what you want; or the sadness that you can’t reciprocate in the way that is desired; or the acknowledgement of your limitations; without criticising yourself – or the other person –for it.

The whole culture, not just individuals within it

Perhaps the main thing that the Consent Cultures movement emphasises is that individual relationships cannot easily become consensual in isolation. When we are in wider cultures where the norms are of non-consensual behaviour, it is very difficult for us to operate differently to that. There have been some really useful writings recently, for example, about how common and taken-for-granted non-consensual practices are within organisations, or within education. For example, people in positions of power over others often force them to do things; implicit rules state that people should be constantly available to their colleagues; and there are pressures to demonstrate ‘success’ in certain ways in competition with others.

Currently consent is taught very little in schools even in sex education, and this is a real problem. But people have pointed out that even if we did teach consent much more, at all levels and across different classes, it would be hard for children and young people to adopt consensual practices when they are often not treated consensually themselves in families and in schools. The idea of Consent Cultures leads us into some vital – but very challenging – conversations about how organisations, institutions, and societies operate.

As Pepper Mint points out:

we are in fact swimming in a soup of nonconsensual power dynamics, where our personal strategies are typically shaped by sets of options that can range from mildly undesirable to downright horrific.

So we need to think about all our relationships and how cultural power dynamics play out in them. For example, do differences in age, gender, cultural background, race, body type, disability, class, role, or anything else between us mean that we have different levels of power in this situation? How do these impact on the likely capacity of ourselves, and the other person, to be freely able to consent (or not) to what is being suggested? Are there pressures in play that make the other person feel that they should act enthusiastically, or say ‘yes’, even when they are not keen? And how might we decrease those pressures, or at least bring them out into the open? This is another useful set of questions to ask about the relationship between Ana and Christian in the Fifty Shades books.

Returning to the sex advice that I’ve been analysing, I feel very aware of how this kind of media often promotes a culture in which consent is difficult if not impossible. For example, there is often an implicit idea that any kind of discrepancy in what people in a relationship want sexually, or how much they want it, is bad. So there is encouragement for people to do things they don’t want to do in order to give the impression that there is no discrepancy.

Instead we could operate under the assumption that discrepancies of all kinds will be present in all our relationships: in terms of what people want to do together and how much they want to do it, as well as in relation to values, goals, and all kinds of other things.

This assumption of discrepancy means that we are less likely to fall into patterns of trying to determine who is right or wrong, or insisting that one person changes entirely to meet the other’s needs. Rather we can look at the discrepancy openly together, considering what we each have to offer, and where are limits are, and figuring out a way forward, for now.

Useful Resources:

There’s a good list of resources on the consent culture blog, and more is being written on this topic all the time if you search for the phrase ‘consent culture’.