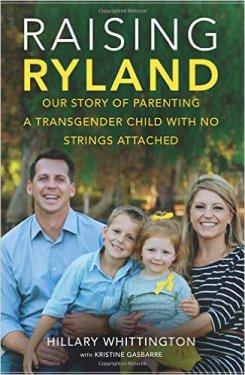

Raising Ryland: Our Story of Parenting A Transgender Child with No Strings Attached

Raising Ryland: Our Story of Parenting A Transgender Child with No Strings Attached. (2015, Harper Collins)

Raising Ryland is about a California family and their struggle and acceptance of their preschooler’s female to male gender transition. Written by the child’s Mother – Hillary Whittington – the book is at its best in chronicling the Parent’s struggle with shame that accompanies their having a gender variant child. Interestingly, this child presents an earlier parallel struggle as hearing impaired (completely deaf – with hearing restored by Cochlear implants). The parents first come to that realization in the book and deal with their shock, sadness, acceptance and treatment. The following struggle with Ryland’s Gender Dysphoria is fraught with much more anxiety and shame.

At first Hillary thinks “I have a tomboy for a daughter”. She goes through a phase of conflating gender non-conforming behavior with the idea that her (then) daughter might be gay. The father is concerned about explaining Ryland’s male dress to people around town. When true gender variance is acknowledged at last – the game “is on” as they say. And here Hillary is brave and honest with her foibles confusion and occasional successes. We cheer and groan along with her as she negotiates birthday parties, Kindergarten teachers, bigoted parents and LGBT award ceremonies. In one incident later in the book Ryland is presenting male at a softball game and has to pee. The coach – not knowing that Ryland is Transgender suggests he just use the bushes, but Hillary scurries him away to the back of their station wagon for an ad-hoc solution… Such are the challenges of protecting privacy vs, disclosure and decisions around when and how to disclose for both the parents and the child.

This book can certainly be helpful for other parents or adults with a gender variant child in their lives to know that others are struggling and have overcome similar feelings of uncertainty, anxiety and shame and have lived to see their child happy and flourishing as never before.

There are, however, a few problems with the book.

When Ryland needs surgery for hearing implants and the surgery date is months away the Mother–in-law calls the hospital to remind them of her many donations. A sooner surgery date is found – perhaps at the expense of a less fortunate child. The book is populated with many such examples early on of the in-law’s ability to solve problems with their wealth. For some the persistent and apparently unconscious class privilege might be off-putting.

But it is just this milieu of suburban Christian white middle class hetero-normativity, of never having been discriminated against or thought of as less-than for any reason whatsoever and suddenly finding yourself considered as “not normal” or “going against God” that will resonate with some readers and give them hope for their own family’s future. I have often found in my own therapy practice that the stigma around being Trans is harder on those who have never experienced stigma before.

It should be noted also that Ryland is an exceptional little boy in that he was able to express and persist in expressing his true gender identity in spite of his parents’ initial disapproval. Most children will take the parental hint and repress the gender non-conforming part of themselves until they are no longer able to do so. Some of these I see at ages 40, 50 or 60 in my practice.