Surf Beach

Surf is an unstaffed Amtrak rail stop on the California coast west of Lompoc. It's part of Vandenberg Space Force Base, but there's public access to a short stretch of beach. Use is light and facilities limited. It's often windy, the water is rough, and we're warned of undertows and rip tides.

When I crossed the tracks and started down to the beach I was hit by an awful smell, the stench of rotting by-the-wind sailors, also known as Velellas. They had been washing up on California beaches by the millions. Fortunately there was enough of a breeze that upwind of the decomposing sailors the air was fresh. The recently stranded ones were beautiful—rimmed in deep blue, their transparent sails still erect.

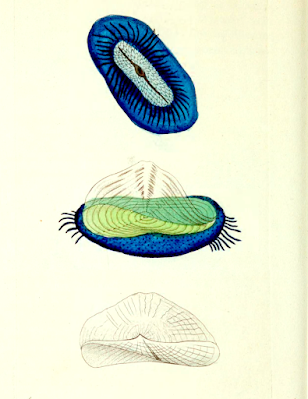

By-the-wind sailors, Velella velella. These are about 5–7 cm across.

When they make the news, Velellas are often called blue jellyfish, being gelatinous. And there was a time when they were thought to be jellyfish ("medusae" among scientists). In 1795, George Shaw published a description and illustration of the Medusa Velella, named by Linnaeus 37 years earlier:"The Medusa Velella ... is an animal of a very singular as well as elegant appearance. It consists of a flat thin body, of an oval form, and beautifully marked by a great number of concentric lines or fibres. On the upper part is situated, in an oblique direction, an upright broad process or sail ... It [the Velella] is of a blue color, except the sail, which is pellucid, and of a glassy appearance."

Shaw was correct about Velella's elegance, but he was wrong about its fundamental nature. It's not "an animal".

Velella Medusa or Blue Sailing Medusa; illustration by F.P. Nodder (Shaw 1795, BHL).

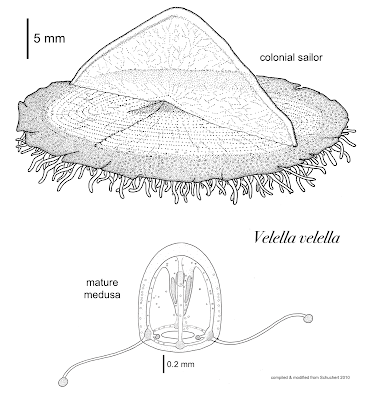

Each sailor is actually a multitude of animals—tiny cylindrical polyps in a colony designed to survive and reproduce on the open sea. Polyps form the "flat thin body" noted by Shaw. It's surrounded by a dark blue float and topped by a chitinous sail, both built by polyps. Some polyps contain photosynthetic plankton that share energy from sunlight with the colony. Some kill by stinging and supply nourishment to the colony via canals. And of course some are devoted to reproduction.

By-the-wind sailors are unisexual, male or female. They reproduce asexually by budding off tiny jellyfish just 1 mm across. This is the medusa stage—solitary creatures rather than colonies. "So Velella really is a pulsing jellyfish, just not when you find it washed up on the beach" (from The Secret Life of Velella).

Note very different scale bars (compiled from Schuchert 2010).

Velella's little jellyfish are sent off into the world with a supply of photosynthetic plankton for nourishment during their first few days of life, before they can hunt on their own. At maturity they produce either eggs or sperm, which eventually develop into new sailors. For more about Velella's fascinating bipartite life cycle, see Sources below.While I was on the beach, pelicans flew by periodically, all headed north.

California brown pelicans, Pelecanus occidentalis californicus.

Back at the parking lot, a local explained that pelicans gather en masse late afternoons at the mouth of the Santa Ynez River, which is on Base property and off-limits to human intruders. She directed me to a county park nearby, where I watched them from an acceptable distance. It was wonderful ... a real treat!

I'm a huge fan of California brown pelicans. I like to watch them flying in formation just above the waves, scanning for fish. I have great memories of communing with them while sea kayaking, when they would sometimes dive quite close to the boat! They strike me as bold confident birds.

I'm a huge fan of California brown pelicans. I like to watch them flying in formation just above the waves, scanning for fish. I have great memories of communing with them while sea kayaking, when they would sometimes dive quite close to the boat! They strike me as bold confident birds.They're larger than their gracefulness suggests—about 4 ft long and 8 lbs in weight, with a wingspan of 6.5+ ft. They dive spectacularly, usually from 10–30 ft above the water but sometimes as high as 60+ ft. Deeper fish require higher dives. Underwater, the pelican's bill opens and its throat pouch stretches to scoop up 2–3 gallons of water plus fish. Back on the surface, the bird tilts its head to release water before swallowing the fish. These pelicans are skilled feeders, eating an estimated 1% of total anchovy biomass off the California coast (they LOVE anchovies).

In the 1960s and 70s, California brown pelicans nearly went extinct. They were feeding on fish contaminated with the agricultural pesticide DDT. It altered the birds' calcium metabolism, making the shells of their eggs so thin that they broke under the parent's weight. In 1971 the subspecies was listed Endangered, and DDT was banned the next year. It worked! Recovery has been dramatic, resulting in delisting in 2009 (see Sources for more).

Brown pelican; photo by William H. Majoros (Wikimedia).

California brown pelican; red skin on pouch during breeding season distinguishes this subspecies. (NPS, Tim Hauf photo).

Sources

Bartels, M. May 2023. Bizarre Blue ‘Jellyfish’ Washing Up on California Beaches Are a Sign of Spring. Scientific American online.

Cornell Lab. Brown Pelican in All About Birds (online).

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. c. 2015. The secret life of Velella: Adrift with the by-the-wind sailor (video). Highly recommended; includes tiny pulsing medusae and philosophical reflection.

National Park Service. California Brown Pelican.

Schuchert, P. 2010. Velella velella, in European athecate hydroids and their medusae. Revue suisse de zoologie 117(3). Velella is on pages 476-480.

Shaw, G. 1795. Blue Sailing Medusa. The Naturalist's Miscellany, v.7. Courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Wikipedia's Velella article has a lot of interesting information.