by the Center for Biological Diversity

“The discovery of this deadly bat disease at Mammoth Cave National Park is a national tragedy,” said Mollie Matteson, a bat advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, which has worked for years to garner attention and funding for the white-nose crisis. “More needs to be done immediately to stop the spread of this disease and help bats.”

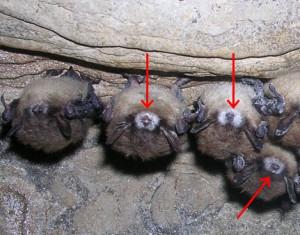

Earlier this month a northern long-eared bat with symptoms of the disease was found in a park cave. Lab testing confirmed the malady, which is caused by an exotic fungus, probably inadvertently introduced to North America from Europe by people.

The Center petitioned for the federal endangered species listing of the northern long-eared bat and the eastern small-footed bat in 2010. It joined bat biologists and several other conservation groups in requesting federal protection of the little brown bat more than two years ago. All three species have been affected by white-nose syndrome; the northern long-eared bat and the little brown bat have declined by 98 percent or more in most northeastern states.

“Two federally endangered bat species are at grave risk from this disease, and several more species urgently need federal protection because they’re now in a nosedive toward extinction,” Matteson said.

The Center has also strongly advocated for more stringent measures, restricting nonessential human access to federal caves and mandating decontamination of gear if cave entry does occur. Diminished cave visitation reduces the risk of fungal spread and lessens disturbance to disease-stressed bats. Bats are likely the primary vector of disease spread, but biologists have gathered substantial evidence that humans can transport white-nose fungal material.

The sick northern long-eared bat at Mammoth was hibernating in Long Cave, the largest bat hibernating site in the park. The cave had been off-limits to park visitors for several decades. Indiana bats and gray bats, both federally protected endangered species, also hibernate in Long Cave, and both are susceptible to white-nose syndrome. Indiana bats have declined 70 percent in states where the disease has been present the longest; the syndrome only recently reached caves occupied by the gray bat, which is found in the Midwest and southern states. No gray bats have yet died from the disease, but scientists are fearful white-nose syndrome could decimate the species rapidly, because the majority of the world’s population hibernates in fewer than 10 caves.

For two years Mammoth has required cave visitors to go through a screening and decontamination procedure in order to reduce the risk of human transfer of the white-nose fungus into the park’s caves from infected sites. The Park Service intends to continue cave tours, despite the fact that white-nose syndrome has now been found at Mammoth; thus park caves will now be a potential source of infection for other bat caves in the surrounding region and beyond.

“The best hope for bats all along has been for research on the disease to speed up, for human travel into caves to slow down, and for government agencies, cave recreationists, and everyone else to take all the protective measures possible to save the bats we have left,” said Matteson. “It will be a sad day indeed when hibernating bats are no longer part of the mystery and beauty of North American caves.”