by Henia Belalia, Cross Posted from Peaceful Uprising

How do activists use social movement history? What lessons can be learned from past movements for social change in our fight to stop climate change? We often rely on lessons and tactics from the U.S. Civil Rights movement. We think this might be the best source for our lessons from the past.

Think again.

How about the Abolition of the Slave Trade? As an activist, I fight for climate justice. As an historian and a scholar of law and history, I study slavery and the slave trade.

The movement for civil rights—certainly the mainstream movement—was based on the perceived need to have equal rights in an existing system. The right to vote, the right to fair housing. An end to segregation. Integration into the existing status quo at every level. And none of these things are bad things. Having equal rights is better than not having equal rights. But even the more radical wing of the civil rights movement questioned this strategy. S.N.C.C. members often asked, “Do we really want to die for the right to vote?”

The movement for climate justice is different. We are demanding “system change, not climate change.”

We are not fighting for access to an existing status quo. We are demanding a fundamental restructuring of society in order to have the possibility of a livable future. So let’s look at social movement history that might be more analogous.

The movement to abolish the Atlantic Slave Trade was a movement to end an entire economic system. The Atlantic Slave Trade, the largest forced migration of people in human history, occurred between the mid-fourteen hundreds to the mid-eighteen hundreds. It is estimated that over 30 million Africans were trafficked, and it was a deadly enterprise . African Captives died on forced marches to the coast, in slave pens on the African littoral, on ships during the “middle passage,” and during their first year of “seasoning” in the Americas. At least 40% of the Africans caught up in the trade were killed by it. This trade had a profound demographic impact on both Africa and the Americas. By the end of the Trade, West and West Central Africa were close to the brink of demographic exhaustion, which left it unable to resist the colonial exploitation and resource extraction that began in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Atlantic slave trade was carried out by shifting European naval powers, each overlapping, but gaining ascendancy in different time periods. The Portuguese were first, then the Dutch. The Spanish and the French became involved, and the English began trading in large numbers during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. England was by far the largest trader in terms of sheer numbers.

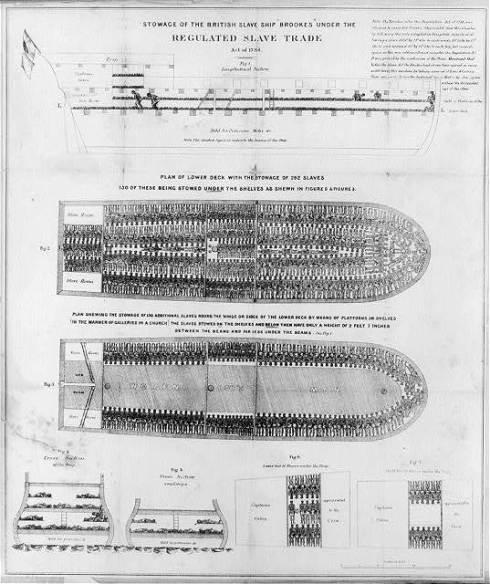

The Atlantic Slave Trade grew exponentially between the last decades of the 1600s and the first of the 19th century, and the movement for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade grew along with it. If we are taught the history of Abolition at all, we are taught about British elite actors, men who were opposed to slavery and the slave trade on religious and moral grounds, and fought within the system for legal approaches to end the slave trade. Some fought for abolition, some for mere amelioration: regulating how many people can be packed into slave ships, and so on. This famous diagram is from a law passed to make the slave trade more humane, and illustrated the maximum number of slaves allowed on a ship.

But other actors were just as crucial: Wide-spread direct action campaigns, organizing boycotts of sugar and cotton and other slave produced goods. Free people of African descent who fought slavery and the slave trade by any means necessary. African captives on who led revolts on slave ships—men and women who refused to be cargo. Recent studies show slave revolts on one in ten voyages, and this caused a sharp increase in the carrying costs of the trade, helping to undermine its economic viability. And Africans on the coast that attacked slave ships before they sailed, cutting them off and freeing captives.

There were other forces that brought about abolition as well—more cynical forces. At the U.S. constitutional convention, colonies in the upper south, especially Virginia, wanted the Atlantic slave trade to end, because Virginia made its money in the domestic trade, breeding slaves and selling them “down the river” (yes, that is where that expression comes from). The result was the slave trade clause of the U.S. Constitution, Article I section 9, which made it that the trade could not be abolished until 1808. (Look it up, it is still there). And there were the big picture changes in the world economy. Four hundred years of slavery and the slave trade allowed for the capital accumulation needed to spark and fund industrialization, and capitalism needed something else. It would not grow by sticking to a proto-industrial agrarian plantation economy. The next stage needed factory workers, “free labor,” and the colonization of Africa and Asia in order to extract the resources needed to industrialize. And let’s not forget that England got to position itself as the naval police force of the Atlantic in its effort to suppress the trade. England did in fact “rule the waves.” All of this brought an end to the Atlantic Slave Trade, abolished in 1807 in England, 1808 in the U.S., and worldwide by the 1830s.

What can we learn from this social movement history? It never works to take the past and graft it on to the present, but past can be prologue. What can we learn by shifting from a Civil Rights paradigm of social change, to an abolitionist one? Doing this shift will help us critically engage with the strategies of the climate justice movement, and help us to develop more useful theories of change.