In his recent New Yorker article, the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande presented an interesting question: Why can’t hospital visits be as enjoyable as a meal at the Cheesecake Factory? His analysis reminded me of the time I stopped at my father’s pharmacy. I was there to pick up his refill for nine different meds. When I pulled up to the drive-thru (yes, drive-thru), I rolled down my window and the young clerk handed me a bag. For a moment, I wasn’t sure if I was picking up a double cheeseburger from McDonald’s or my dad’s prescription meds from RiteAid.

The pharmacist is arguably the most accessible professional in the health-care system. Many pharmacies are open all hours, and often it’s the closest medical destination to home. But while the average patient interacts with his or her pharmacist between 12 and 15 times a year, few patients have a relationship with their pharmacists. And although the local pharmacy can fill prescriptions, most patients do not turn to their pharmacist for support.

It’s surprising considering the problem of adherence. People don’t follow their medication regimen for a variety of reasons. Some simply forget, others struggle to afford refills. Some patients can experience severe side effects or have conflicts with other medications, while others stop because they “feel better” and believe their problem has been fixed, which cuts short any long-term treatment benefits. According to a 2011 PhRMA profile, approximately 75 percent of people in the United States who take medication are not adhering in some way or another. This poor compliance costs the health-care system close to $100 billion annually.

The Rise of Fast Meds

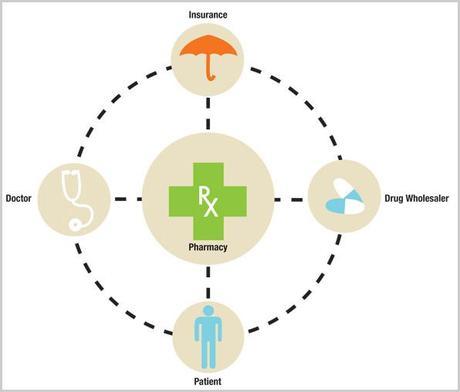

Despite this very expensive problem, the modern pharmacy has been optimized for efficiency, much like fast-food restaurants in the 1980s. Pharmacies are offsetting low-margin commodity sales of generic drugs with high-volume throughput. This means that the pharmacist doesn’t have the time or the incentive to engage in personalized service. And yet the pharmacy is in a unique position to act as a link between the patient, his or her physician, the pharmaceutical industry, and insurance companies.

We’re seeing many retailers and hospitals investing resources in these “fast med” retail clinics. CVS Caremark has already instituted “Minute Clinics” in 550 locations across the U.S. to provide basic medical procedures like flu shots, immunizations, and physical exams. Similarly, Walgreen’s “Community Pharmacy” is attempting to bring the pharmacist forward and make him or her more accessible. What’s striking about Walgreen’s is that the pharmacy still looks and feels much like a fast-med pharmacy. There’s a stark difference between that environment and the old days of neighborhood pharmacies and apothecaries, which were warmer and more inviting (see Dan Formosa’s recent article, “Dissolving The Barrier Between Patients and Pharmacists”). In those stores, patients felt comfortable because the environment was designed to encourage conversation and consultation.

The healing influence of well-designed environments is an emerging trend in the medical field. Results of a recent study at Pittsburgh’s Montefiore Hospital showed that patients recovering from surgery in rooms with ample sunlight had 21 percent lower drug costs and were discharged two days earlier than patients recovering in traditional hospital rooms (as Daniel Pink details in his A Whole New Mind). In a competitive marketplace, fast-food chains such as Starbucks, Panera, and Chipotle have created appetizing decors and customized service to differentiate themselves. Similar to hospitals and clinics, they, too, have to comply with stringent health standards–yet they have managed to do so without compromising the overall experience.

Designing the Next-Gen Pharmacy

At Smart Design, we have studied patients during the first six months following the diagnosis of a chronic illness. What we learned is that it’s a critical phase when patients are hurting both physically and emotionally, their lifestyle needs to adapt, and they’re actively seeking information and guidance. Some patients fall into denial that they have an illness at all. These first six months can be an opportunity for a pharmacist to build a lasting relationship with a new or existing customer at a time when they are most open to accepting help.

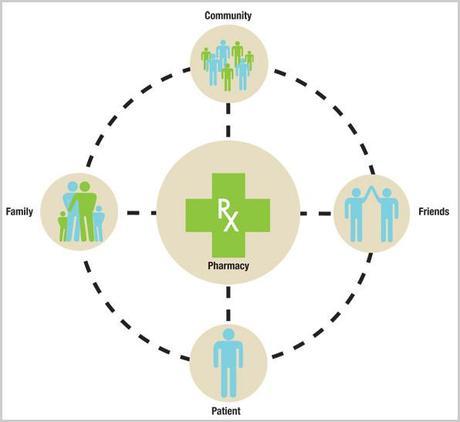

Mentorship, support, and sharing of anecdotal information are some of the best ways to influence behavior change, especially when it comes from peers. In the spirit of organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Weight Watchers, I can imagine the next-gen pharmacy offering a meeting space for local patient groups or lectures on disease management. It would be like bringing WebMD and PatientsLikeMe to life.

With the growth of evidence-based medicine, it looks inevitable that insurance companies will require pharmacies to prove compliance before reimbursing prescription costs. Pharmacies that shift their focus from fulfillment to adherence can become a market leader in the minds of physicians, patients, and insurers. Likewise, retailers that offer resources and support to patients at their time of need have the opportunity to win customers for the rest of their lives. Over 79 million baby boomers, including my dad, are ready to be served.

This article was co-authored by Jeffrey Hirsch of Syracuse University.