Green leaves and red stems just above center are the plant of interest.

“When I discovered a new plant, I sat down beside it for a minute or a day, to make its acquaintance and hear what it had to tell.” John Muir, in Explorations in the Great Tuolumne Cañon, 1873.

John Muir—our great naturalist and conservationist—often wandered alone in the Sierra Nevada of California, passionately admiring and studying the plants. The vast wilderness enraptured him, but it also brought on feelings of loneliness at times. Perhaps that’s why he referred to plants as “friends” (1).Muir came to mind last June, as I got to know a new plant friend near South Pass, at the southern end of the Wind River Mountains. For days I wandered through expansive sagebrush gardens bright with displays of pink, yellow, blue and white spring flowers. But I had to ignore them. I was being paid to search for rockcresses (genus Boechera, formerly Arabis)—small thin drab easily-overlooked plants. But I didn't mind too much. I love the sweeping landscapes and granite blobs of the South Pass area. So does my field assistant.

But I didn't mind too much. I love the sweeping landscapes and granite blobs of the South Pass area. So does my field assistant.

Strolling with eyes glued to the ground, I pondered my fate—consigned to survey a challenging and esthetically unremarkable plant, the russeola rockcress (Boechera pendulina var. russeola). It is neither showy nor rare. Even worse, it no longer exists according to the latest treatment of the genus Boechera. So or course the more I thought about it, the more I became enamored of this plant! (I’m biased towards underdogs)

Strolling with eyes glued to the ground, I pondered my fate—consigned to survey a challenging and esthetically unremarkable plant, the russeola rockcress (Boechera pendulina var. russeola). It is neither showy nor rare. Even worse, it no longer exists according to the latest treatment of the genus Boechera. So or course the more I thought about it, the more I became enamored of this plant! (I’m biased towards underdogs)

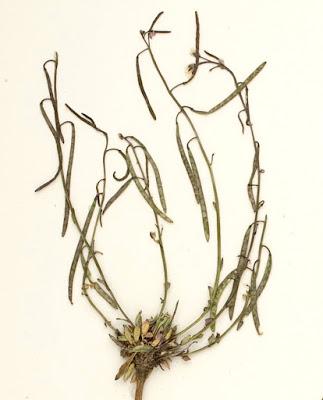

“But we know that however faint, and however shaded, no part of it is lost, for all color is received into the eyes of God.” John Muir (unpublished Pelican Bay Lodge manuscript)The flowers of the all various rockcresses are small, white-to-purple, and 4-petaled. They’re useless for identifying plants to species. Mature seedpods (siliques) and basal leaves are required. One of the first things I learned from the russeola rockcress was that it can be recognized by the combination of pendulous siliques, reddish stems (hence russeola), and ciliate-margined but otherwise bare basal leaves. This probably sounds impossible to spot at the scale of these plants (a few inches tall at most), but the power of a well-developed search image is astonishing. Let’s have a look.

Below is a specimen from the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, University of Wyoming. Note the tiny white flowers. The normally pendulous arrangement of the siliques was distorted with pressing. The reddish color of the stems disappeared with drying.

The next photos show just how un-photogenic russeola rockcress is in the field, in part because the area is often windy. Still, the distinguishing features are obvious once one gets to know them. And fortunately, russeola prefers sparsely vegetated microsites.

The next photos show just how un-photogenic russeola rockcress is in the field, in part because the area is often windy. Still, the distinguishing features are obvious once one gets to know them. And fortunately, russeola prefers sparsely vegetated microsites.

Green leaves with ciliate margins (coarse hairs), reddish stems, pendulous blurry siliques.

Handlens is 2.5 cm long (1 in).

Sometimes the shadows are more obvious than the seedpods that cast them.

Distinctive upright green basal leaves at pencil tip, with reddish stem waving in the wind.

Ciliate-margined leaves; up close those hairs look gnarly! (click on image to view)

Though not rare overall, the russeola rockcress is uncommon in the South Pass area, which makes hunting for it fascinating—why does it only grow where it does? Muir pondered the same question; for him, learning why plants grow where they do was learning a bit more about the marvelous work of God.After four long days of searching, I had learned that russeola (we're now on a first-name basis) is indeed restricted to rock. But it doesn’t grow in rock, i.e., not in crevices. That’s the habitat of the littleleaf rockcress, Boechera microphylla. Russeola prefers pockets of gravelly soil (decomposed granite) that develop in low, almost ground-level exposures of rock at the base of the big granite blobs.

Collection of littleleaf rockcress from South Pass area. Note upright very thin siliques.

Low rock outcrops such as this are prime targets for russeola survey.

Russeola grows on coarse granitic soil that develops in pockets in the low outcrops.

Russeola generally prefers less vegetated areas, such as this low ridge (dike?).

What's going on here?!

Dropseed rockcress, Boechera pendulocarpa (not to be confused with "pendulina"), frequently occurs with russeola on the same microsites. It’s the gray plant in the middle of the photo above, along with two russeola plants. But dropseed rockcress is a less picky plant, and it grows in a variety of habitats. Though we’re now good friends, russeola has not revealed all of its secrets. I looked at a LOT of what appeared to be perfectly good habitat, but russeola wasn’t there. I wasn’t disappointed, or even surprised. After all these years I know that plants often don't grow everywhere it seems they could. In fact we should expect that, for a plant has to get to those perfect places—a seed has to land there. The great plant ecologist Henry A. Gleason made this clear, yet we often forget, perhaps driven by the human need to predict.“Does a plant always grow in every habitat suitable to it and over the whole extent of the habitat? The answer is emphatically no. As previously stated, plants attain their range by migration. Possibly this plant is on its migratory way and has not yet arrived. … Possibly it has only recently arrived and has not yet had time to spread over the whole extent of the habitat. Possibly it is meeting with such strenuous competition from other plants that only a few individuals have a chance to grow.” Gleason and Cronquist, The Natural Geography of Plants, 1964 (2)

Russeola grows on bare gravelly soil at the base of this small outcrop.

Finally, some readers may wonder why was I paid to look for a plant that’s neither showy nor rare, nor even recognized by “experts.” I will try to explain. This is a long and winding tale that the faint of heart may wish to skip.

The main objective of our project was to locate additional populations of the small rockcress, Boechera pusilla, a globally-rare plant known from a single population (near South Pass). However, in the latest revision of the genus, authors Al-Shehbaz and Windham inadvertently (I think) expanded B. pusilla to include plants formerly called B. pendulina var. russeola. Does this mean that the small rockcress is no longer rare? No. It means the key and species descriptions were poorly constructed.The authors lumped together the two varieties of Boechera pendulina—the typical one and russeola—though they acknowledged there’s no evidence they are conspecific. As a result (unintended), their key and descriptions do not address the plants we call russeola. Russeola material now keys to small rockcress (the very rare one), but only because there is no better match. As we discovered during post-field season herbarium study, russeola rockcress and small rockcress clearly are different. Hoping to eliminate the confusion, we collected and preserved leaves for DNA analysis, but Al-Shehbaz and Windham declined the offer, explaining they had insufficient funding to add another sample.Thus russeola’s taxonomic status remains in limbo (3). But who cares?! The plants certainly don’t. Whatever we call them, these plants are real, and I’m happy to have made their acquaintance.

A dense “stand” of russeola—not a common situation.

(1) Muir’s passion for plants and his botany adventures are wonderfully recounted in Nature’s Beloved Son; rediscovering John Muir’s botanical legacy (Gisel and Joseph 2008).

(2) The first 10 chapters of The Natural Geography of Plants, including the discussion of why plants are restricted in distribution, were written by Gleason. Arthur Cronquist completed the book (second half) at Gleason’s request.(3) Other experts recognize the russeola rockcress as a valid taxon. For example, our material clearly keys to and fits descriptions of Boechera pendulina var. russeola in Vascular Plants of Wyoming 3rd ed. (Dorn 2001) and Rollins’s 1982 treatment of North American Arabis (Boechera).