February is a pretty busy time for somebody who writes about sex, gender and relationships what with the coinciding of LGBT history month and Valentine’s Day. This year, however, I thought I could rest up a bit on February 14th given that I said everything I wanted to say about the celebration of romantic love last Valentine.

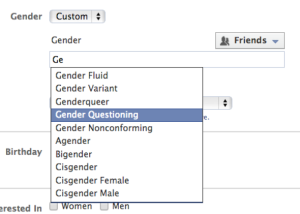

I was wrong. Facebook chose February 14th 2014 to do one of the most exciting things that has happened in the area of gender and social media for a long time. It changed its gender option so that, instead of choosing from ‘male’ and ‘female’, users could pick from a range of over 50 gender terms (listed at the end of this post), as well as choosing to be referred to as ‘they’ if they didn’t want a gendered pronoun (‘he’ or ‘she’).

As usual, rather than getting into whether this is a good move or a bad move by Facebook, I am going to ask a different couple of questions which I think are more helpful: What does this change open up, and what does it close down? As with most shifts, what Facebook has done achieves something which is important and useful, but in other ways it is problematic and limited. Reframing the question to what is opened up and closed down gets away from polarised ideas of right and wrong, good and bad. Instead it acknowledges the complexity of the situation and the fact that something can simultaneously expand understanding in some ways and constrain it in others.

If you want to know how to go about changing your own Facebook gender I’ve included a brief guide at the end of this post.

Opening up

The main, extremely important, thing that the move to a range of gender options does is to demonstrate to people that gender is not dichotomous. The previous options – like most depictions of gender in western cultures – suggested that everybody could be captured under one of two genders: either you are ‘male’ or you are ‘female’. The new options suggest that this is far too limiting and that there are actually over 50 different possible gender categories, and presumably more.

Why is this important? Two reasons: First it means that those who don’t experience their gender as ‘male’ or ‘female’ can feel both visible and included, and perhaps this paves the way to further social inclusion as other organisations and bodies follow Facebook’s example. Second it means that everybody can see that the model of gender which this huge social networking service adopts is one of diversity rather than dichotomy.

Starting with the first reason, the range of terms now offered mean that many people are able to pick the exact label that matches their experience of gender, rather than feeling forced into a box which doesn’t fit them. It may well also give many people a sense of greater validity, and encourage policy-makers, schools, workplaces and practitioners to move towards similar acceptance of multiple genders (and using the appropriate terminology). The impact of this could be huge given the current high rates of discrimination against trans* and non-binary gender people, and the associated high rates of mental health problems and suicide in these groups. As somebody who identifies outside the gender binary myself, I can feel this shift. Of course I shouldn’t need a big social networking service to tell me that I’m legitimate, but it does make a palpable difference to how I feel right now writing this post.

Increasing numbers of people find that the gender dichotomy doesn’t capture their experience. For example, the US Human Rights Campaign reports that nearly 10% of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* youth were ‘gender expansive’. The recent UK Youth Chances survey found that 5% of those surveyed identified as something other than ‘male’ or ‘female’. Of course these statistics are percentages of the young LGBT people who were willing and able to complete these surveys, not of the population as a whole, but they are certainly suggestive. And, of course, it is not clear how many others would identify in such ways if the wider cultural understanding shifted from gender dichotomy to gender diversity.

This brings us to the second reason why what Facebook did was important. The gender dichotomy is not just problematic for those it excludes, but also for those who it includes. This is something that I spent a whole chapter on in Rewriting the Rules, but to attempt a brief summary, the idea of two, and only two, genders is associated with commonly held attitudes that those genders are ‘opposite’ to each other and that they involve having to behave in stereotypically ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ ways. When people hold rigidly to such attitudes and try to conform to limited ideals of masculinity and femininity they often struggle. For example, high rates of depression and body image problems in women, and high rates of criminal conviction and suicide in men, have all been linked to limiting and rigid ideas of what it means to be a woman or a man. Also, gender stereotypes limit people’s opportunities in the world in various material ways.

So, while many people will not feel any need to change their previous ‘male’ or ‘female’ status on Facebook, their increased knowledge of the existence of multiple categories and the very different model of gender that these suggest, may help them to hold onto their own gender more lightly and/or to be more flexible in their own ideas about what ‘counts’ as masculine or feminine in ways that are helpful to them.

A few of the specific terms the Facebook has included are worth noting here before we go on. There are words that enable people to identify as neutral or without any gender, words that enable people them say that they combine aspects of masculinity and femininity, words that capture the idea that there are third, fourth or multiple genders, and words that enable people to say that their gender is something that has – or can – change over time (see the bottom of this post for the complete list). All of these expand our understandings of how gender can operate in interesting and useful ways.

One word that has caused particular debate following the change is ‘cis’ or ‘cisgender’. This is the word for people who remain in the gender that they were assigned at birth (unlike trans* people). A lot of people balked at the idea of having to change their status from simply ‘male’ or ‘female’ to something like ‘cis man’ or ‘cis woman’. Of course nobody is forcing them to do this, and it is up to each individual to decide whether they want to make a change or not, but the following analogy might help those who are considering it. People who aren’t gay, lesbian or bisexual generally wouldn’t claim – any more – that they were just ‘regular people’ or had a ‘normal sexuality’. Rather they would accept the label of ‘heterosexual’ or ‘straight’: we all have a sexuality and it is offensive to suggest that some sexualities are more normal or acceptable than others and therefore don’t require labelling. Similarly, when it comes to gender status, it is useful if people who aren’t trans* use the term cis or cisgender in order to avoid the impression that being trans* is somehow less acceptable or normal. Of course much of the time gender status (whether you are trans* or cis) just isn’t relevant, and most people would refer to themselves simply as a woman, a man, or a person, regardless of whether they are cis, trans* or otherwise.

Closing down

So what are the problems with Facebook’s new ways of capturing gender? Several people have asked whether there is a cynical aspect to the change given that it may enable companies to better target their social media advertising. But are there also limitations and constraints in what it offers for our understanding of gender?

The first point to make is that the list is not exhaustive. For example it does not include the terms femme and butch which are perhaps two of the most common words which LGBT+ people use to refer to their gender. Consider how it might feel if a major organisation finally made a change designed to encompass people like yourself, but then failed to include your own experience within that. Also, when you choose a custom gender, you no longer have the options of ‘male’ or ‘female’ available to you, so there is still perhaps the suggestion that people are either ‘male’, ‘female’ or a ‘custom gender’, rather than all of the genders being placed on an equal footing.

Additionally, in relation to this, the vast majority of the new terms developed in a white, US, context and therefore will not be applicable globally. Of course the change has only rolled out in the US so far, and I’m not sure what gender terms Facebook has previously had available in South Asia, for example. However, even among those currently living in the multicultural US, there are many people who will understand and experience their genders in ways which are not captured on the list. For example, as I understand it, no list of gender terms (separate from sexual identity terms) could ever completely capture Thai identities which often combine elements of gender and sexual identity in one word. There is one word on the list which refers to an indigenous North American gender identity (two spirit). However, there is a risk that this implies that there is one unified indigenous American understanding of gender rather than capturing the diversity of understandings which are actually present across indigenous American communities.

The suggestion of an open box for people to write in whatever gender term they use themselves would be one solution to such issues. However a list of categories probably lends itself more easily to data analysis. This could potentially be useful if Facebook were able to release figures of the numbers of people who are identifying in each way for the reasons of visibility and inclusion mentioned previously.

Finally, having any kind of gender option, by its very existence, implies that gender is relevant. Indeed, it implies that it is perhaps the most important feature of your identity given that it is the first thing that comes up on Facebook’s ‘basic information’.

Some people have argued that it would be better to have no box for gender rather than just expanding the list of possible genders. As mentioned before, a person’s gender status (whether they are cis, trans* or otherwise) is rarely relevant, and – for important reasons – most people generally do not choose to reveal their gender status unless directly relevant (for certain medical procedures, for example). Similarly, although we are used to being asked our gender on all kinds of surveys and documentation, it is actually very rarely relevant. Research has found that being asked our gender primes us to behave, and even think, in more gender stereotypical ways which can limit us, and the opportunities that are available to us. Perhaps having no gender box at all would be a more radical step in questioning how we currently understand – and prioritise – gender.

Conclusions

In conclusion I welcome the change that Facebook has made, not least because it opens up the possibility for exactly the kinds of conversations that I’m referring to here. I hope that it will encourage people to keep reflecting on their own understandings of genders in ways that are helpful to themselves and to those around them.

Changing your Facebook gender

If you want to change your gender and/or pronoun on Facebook and you live outside the US, you need to go to the ‘settings’ option on the dropdown menu at the top right of the home page, pick ‘language’ and change it to ‘English (US)’. Once you’ve done that, go to your own Facebook page and click ‘update info’. Choose to edit your basic information. Under ‘gender’ pick ‘custom’ and you will then be able to write in one of the list of words below (you can’t just write in your own preferred term if it is not on the list). You can also answer the question ‘What pronoun do you prefer’ with ‘female’, ‘male’ or ‘neutral’.

The following are the 56 gender options identified by ABC News in addition to the previous ‘male’ and ‘female’ options (Okay there are 58 options altogether not 57, but accuracy wouldn’t have allowed me to build a rather forced reference to a Bruce Springstein song into the title of this post).

- Agender

- Androgyne

- Androgynous

- Bigender

- Cis

- Cisgender

- Cis Female

- Cis Male

- Cis Man

- Cis Woman

- Cisgender Female

- Cisgender Male

- Cisgender Man

- Cisgender Woman

- Female to Male

- FTM

- Gender Fluid

- Gender Nonconforming

- Gender Questioning

- Gender Variant

- Genderqueer

- Intersex

- Male to Female

- MTF

- Neither

- Neutrois

- Non-binary

- Other

- Pangender

- Trans

- Trans*

- Trans Female

- Trans* Female

- Trans Male

- Trans* Male

- Trans Man

- Trans* Man

- Trans Person

- Trans* Person

- Trans Woman

- Trans* Woman

- Transfeminine

- Transgender

- Transgender Female

- Transgender Male

- Transgender Man

- Transgender Person

- Transgender Woman

- Transmasculine

- Transsexual

- Transsexual Female

- Transsexual Male

- Transsexual Man

- Transsexual Person

- Transsexual Woman

- Two-Spirit

Read more

Paris Lees’s reflections on the facebook shift are here.

A DIVA article that I wrote on non-binary gender more broadly is here.