Several weeks ago we wondered aloud whether ethical considerations should factor into our travel decisions. That post prompted a lively debate that helped us refine our thinking on the subject. Since then, fellow travel blogger Wandering Earl has written several thought provoking articles leading up to, and including, his recent trip to North Korea.

We agree with Earl that under normal circumstances the conscientious traveler is a positive force in the world. At our best we are ambassadors, educators, volunteers and economic engines for struggling communities. And it is for those reasons that we encourage people to travel freely and widely. But we also know that while those things are often true, they are not always true.

North Korea stands out as one glaring example of a country that is particularly immune to the benefits travelers normally bring. It’s also a place where tourism has the potential to cause real harm.

In recent years the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) has slowly opened its borders to western tourism. We sense it’s a destination that will grow in popularity among hard core travelers. Earl may be among the first to go, but I expect others will follow. Should you?

It’s no secret that the North Korean government is regarded as one of the most vicious and cruel regimes of modern times. According to Human Rights Watch the “government regularly arrests, abuses, tortures, and imprisons citizens for a variety of economic crimes.” Those crimes include such mundane activities as “violating travel permits, engaging in private trading activities, using mobile phones to call overseas, and possessing DVDs.”

Worse is its treatment of accused political dissidents who risk having their entire families sentenced to a lifetime of slave labor without trial or recourse. Through a policy known as Three Generations of Punishment the government even detains children born in prison camps as retribution for the alleged crimes of an ancestor.

60 Minutes Interviews an Escapee Born in a North Korean Prison

In testimony before the United Nations last week, another escapee from a different North Korean gulag described his experience this way:

My parents didn’t last even a year. They died from hunger. There were so many ways to die in Yodok. People could have their limbs chopped off while cutting wood, they could die from parasites, or from hunger; there was so much death that the streets would be lined with dead bodies.”

So how do travelers justify going to such a place? Some, unfortunately, go without question. Others, like Wandering Earl, take a more thoughtful approach.

Before heading off to Pyongyang, Earl wrote a detailed post explaining why he doesn’t let human rights concerns affect his travel decisions. When I asked him specifically about North Korea, he provided links to a handful of articles supporting tourism to the DPRK.

You can read those articles here and here.

Let’s critique their arguments.

It’s all about the Benjamins

Tad Farrell, the founder of NKNews, tells us that we shouldn’t worry about traveling to North Korea because our individual impact is trivial.

Last year North Korea’s GDP was (conservatively) estimated by the CIA to be approx $40 billion. When considering that about 4,000 Westerners go per year, the revenue generated by tourist visits comes to about $400,000 per year – or 0.001% of the sum total of the DPRK GDP. These figures are so small that frankly it is absurd to think that touring North Korea will in any way impact what the North Korean government chooses to spend its money on.”

First of all, Mr. Farrell uses the wrong comparison to judge the size and impact of tourism on the North Korean government. Total GDP, which counts all transactions in a country, is not the right denominator. A much better measure for comparison is the amount of “hard currency” available to the government.

To see why we first need to discuss how the North Korean economy is different from the ones we’re more familiar with.

Unlike more open economies North Korean leaders can’t simply convert their domestic money (the Won) into other world currencies or borrow those currencies on world markets. Nobody outside of North Korea will accept Won as payment for anything. If the government wants to buy foreign goods, it must first obtain enough foreign currency (typically dollars, Euros, or Renminbi) to make the purchases.

And the DPRK really wants to buy foreign goods. One way the government keeps its generals happy is by plying them with French wine and Russian caviar. Bestowing foreign luxuries is a critical tool the ruling elite uses to retain power. But getting enough “hard currency” to pay for such extravagances is difficult for the regime.

Tourism is one avenue for bringing hard currency into the country (selling methamphetamine internationally is another).

Doing a small amount of harm is still doing harm

In order to visit North Korea you have to book an all-inclusive tour, either directly or indirectly, from a government controlled travel agency. The tours we’ve seen offered by western tour agencies cost about €1,500 per person. The western agency will take some of that money for itself but will pass the rest along to the North Korean travel agency in the form of Euros. The government takes those Euros and then provides your hotel, meals, and transportation with state-owned resources.

It’s now easy to see why a Euro generated through tourism has far more value to North Korean rulers than an equivalent amount of Won spent locally. It’s also easy to see why Mr. Farrell’s comparison of tourism revenues to total GDP is misplaced.

A rural farmer delivering €1,000 worth of chickens to Pyongyang is recorded as €1,000 in GDP. But if Kim Jong Un wants to reward a general for crushing a local uprising with a €1,000 Cartier watch he can’t use those chickens to buy one. He can, however, purchase it with the proceeds from your €1,500 tour package.

While Mr. Farrell may still contend that an individual tourist’s ~€1,500 contribution to North Korea’s “Despot Self Preservation Fund” is small compared to the government’s total needs, size isn’t really the relevant issue. Doing a small amount of harm is still doing harm. And as travelers we should really aim to avoid doing any harm at all.

The better question to explore is whether any positive aspects of our travels more than offset the harm done by giving money to the North Korean horror factory. One argument we hear routinely is that tourism helps local economies and their struggling workers. That is often true. But once again, North Korea is a special case.

Market principles don’t apply

The North Korean economy is unlike any we’re accustomed to. Our normal understanding of the way commerce works doesn’t apply. There are no locally owned shops or guest houses where tourists can direct their spending. The restaurants where you eat and the hotels where you sleep are all government owned.

On your tightly controlled, all-inclusive, tour the government largely directs how you spend your money while inside North Korea. Tourists do have limited opportunities to spend Euros on drinks and souvenirs but it’s unreasonable to expect that the sellers actually profit from those transactions. Profits, after all, are forbidden.

It’s also unreasonable to expect that your commerce will benefit anyone but the ruling elite. The farmer who produces more food to feed tourists won’t earn any more money as a result. In fact, he may not be paid anything at all.

Many North Koreans are forced to work without pay. It’s a crime not to oblige. Instead of earning monetary wages workers survive on government rations and increasingly on black market activities. In such an environment it’s hard to see how tourist dollars have any chance of reaching the struggling masses.

For these reasons we believe that the economic case argues decisively against traveling to North Korea. Tourism provides the government with the hard currency it desperately needs to perpetuate its oppressive regime while offering few obvious benefits to ordinary citizens.

If we are to travel to this country in good conscience, we need to find a more compelling reason. Wandering Earl thinks he has one.

By traveling to countries that are home to movements or policies that you don’t agree with, you also have a chance to create some open, healthy debate. Human interaction and the exchange of ideas leads people to re-evaluate their beliefs. After all, this is exactly how I’ve grown and changed as a person over the years myself. I’ve met people all over the world who think differently than I do and I’ve listened to their stories, tried to understand their points of view and then, I’ve examined my own belief system and often made adjustments as a result.”

This is another example of a good general argument that has limited bearing on the specific case of North Korea.

It’s only a conversation when we’re both allowed to speak freely

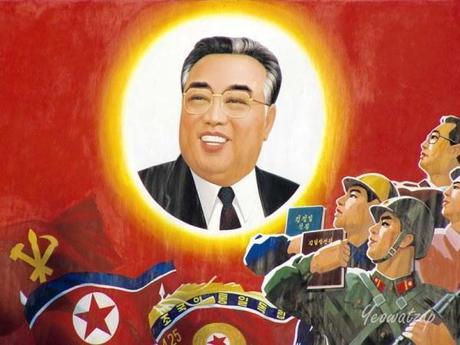

Unfortunately for the North Korean people there is no possibility for an “open and healthy debate” because their government brooks no dissent. Its citizens are monitored continuously and ranked according to their perceived allegiance to the state, even to the point of having their homes inspected to assure their required portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il are properly hung and cared for. To speak an unauthorized opinion inside North Korea is to risk slave labor for yourself, your family and possibly your posterity.

Even if you, as a tourist, meet and impress a dozen locals during your visit the “conversation” basically ends there. But not for you.

You return home and tell your friends and neighbors about the great trip you had. Maybe you even blog about it, as Earl did to his thousands of followers. And though you try your best to be balanced, your reporting comes across as favorable because, lets face it, you had a good time.

You didn’t see overt oppression or prison camps while you were in Pyongyang. Sure you witnessed propaganda billboards and a disturbing level of conformity, but your experience in the country bore little resemblance to all those reports you read before your trip.

And that, to me, seems problematic.

I have megaphone they have a muzzle

Although the places you visited were every bit as real as the places you couldn’t go, the impressions you take home and share give a distorted picture of the country. Or, more precisely, they paint the picture the North Korean government wants to project.

And while the government actively suppresses the conversation you hoped to start internally, your conversations externally help soften the image of a brutal regime in regions of the world where public opinion actually matters.

Still, Andrei Lankov, an associate professor at Seoul’s Kookmin University, sees more sunshine than darkness in North Korean tourism. According to his reasoning,

The only way to promote change, evolutionary or revolutionary, is to bring North Koreans into contact with the outside world. The North Korean dictator and his elite might see partial exchanges as an easy way to earn money, which is necessary for them to maintain their caviar and cognac lifestyle. In the short term they are probably right. But in the long term, the (cultural) exchanges will make breaches in the once monolith wall of information blockade. Sooner or later, those breaches will become decisive.”

The idea that the knowledge tourists bring to the North Korean people will eventually spur change is an appealing one. Hearing firsthand accounts from foreigners about life beyond the DMZ must encourage, as Earl puts it, “a bit of yearning for what’s on the outside.” That yearning is the very stuff from which revolutions are made. It is a hopeful thought.

The obvious retort is that Mr. Lankov is advocating trading something immediate and certain for something distant and unknowable. In the short run, Kim Jong Un will use our money to perpetuate his regime along with all of it’s oppression, torture, and death.

In the longer term? No one knows. Not even the good professor.

And while Mr. Lankov certainly knows far more about the inner workings of North Korea than I do, he knows far less about what the regime needs to stay in power than does the government itself. And the government’s actions speak loudly.

Through the tentative opening of its borders to highly controlled tourism the DPRK has signaled that it needs our money more than it fears our presence or our influence. We hesitate before second-guessing the government’s understanding of what it requires to retain power.

We shudder at the thought of giving it what it needs.