I have a confession to make: I didn't cry at Logan. It's nothing to do with the film's quality or emotional power. The film has the ability to make you care whether or not a once-invulnerable mutant with metal claws makes peace with both his past and surrogate father figure and forms a bond with the genetically cloned daughter he didn't know he had. No small feat, that. In fact, the movie hasn't really left my mind since I saw it. I sat, I watched, and all I could think was, "I can't believe they've made a film this bleak, this death-obsessed, this character-driven, and released it as though it was just another popcorn Marvel blockbuster." It's certainly the most emotionally-wrenching superhero film I've seen, and it reminds you that no genre is too mainstream to be raised to art form level.

After the film ended, I called my mother to tell her how much I liked it, and to attempt to delicately dissuade her from trying to see it. You see, my mother is genetically incapable of stoically watching a movie. Happy endings, sad endings, it doesn't matter. She'll shed tears to the point of dehydration at a hat's drop. Her response was fitting: "Well, I don't want to see it if they get killed in some brutal way." My response: "Well, then you really don't want to see it." Yes, Logan and Charles Xavier, or at least these iterations of them, are dead.

Comic book characters come and go with the rapidity of Spinal Tap drummers, but in the comic cinematic universe, if you're not Uncle Ben or Bruce Wayne's parents, the odds of survival are definitely in your favor. Logan has the audacity to bring its central characters, central characters who have been part of our cinematic lives for nearly two decades, and take them out. Now, when I watch The Wolverine or X2 all I can think is, "I know how you die." We despair for fictional characters because we grow attached to them, and we've had years to develop an emotional attachment to Xavier and Logan. From the reactions I've heard from critics and general audience members, the attachment was there in full force.

But is that all there is to the emotional reaction people are having to Logan? Are well all just mourning the end of an era and recognizing, as Xavier puts it in the movie, "life's impermanence"? Or is Logan's superhuman ability to make some of us cry more due to the quality of its storytelling, which exhibits a maturity and level of nuance rarely seen in the comic book movie genre? It's likely a combination of both.

The signs of impending heartbreak are apparent from the very beginning as we watch a weathered and scarred Logan struggle to muster the necessary strength and rage to deal with a gang of would-be tire thieves. It's a scene which would more normally happen in a western or gangster film, but here it is at the start of a comic book movie, Logan director James Mangold's way of signaling that we're in for a very different kind of X-Men film. This is to be an X-Men film in which flawed, damaged characters have to defend themselves against ruthless, vicious characters. The Wolverine we've come to know over these past 17 years isn't the same man he used to be. He's vulnerable and haggard. It's easily apparent he is living on borrowed time, in a world that has no time for the vulnerable. Think of it as No Country for Old Man Logan.

Having watched the X-Men franchise since I was a teenager, there's a palpable sense of loss at seeing not just Wolverine but also Charles Xavier, both iconic characters, succumbing to decay and death. There's a moment in which a dementia-addled Xavier confronts Logan with a terrible accusation: "You're waiting for me to die." The line stings, because there's such truth in that statement, but it misses the fact that Logan is also waiting to die. He's working as a limo driver to make ends meet (and procure the medications needed to keep Xavier from seizing and killing everyone in the near vicinity), drifting through life, and drowning the memories of his past in alcohol.

Sure, he has this plan to buy a boat and take Charles somewhere to allow them to live their final days in peace, but that dream feels as quixotic as the farm Of Mice and Men 's Lenny and George always say they're going to purchase. It keeps them going, but it never really feels like a tangible solution.

Rarely if ever has a superhero movie rendered our heroes so human, so frail, so physically and psychologically wounded. I watched Logan with an equal mix of dread that the film would both kill off these iconic characters and that it wouldn't. I hated the thought of watching the two of them die, but even more, I hated the idea that the film would give us a bleak, doom-laden setup and not follow through with its foreshadowing.

My emotions are complicated in relation to Xavier. Patrick Stewart is 76, made-up to look in his 90s, and the trailers largely gave his character's fate away. His death is all but assured, and we've seen Charles die before (in the not-so last Last Stand). Plus, we now have James McAvoy as a younger version of Charles, with the lingering possibility of more depending on what the producers decide to do after Apocalypse. In a way, Charles has already been replaced.

Wolverine, though, exists as the one constant in the ever-changing comic book movie universe of the past two decades. Other cinematic superheroes have come and gone, been recast and rebooted, but Hugh Jackman's Wolverine has been omnipresent. He's a character built around ferocity and invincibility. Watching his body break down, vision deteriorate, and signature adamantium claws slowly poison him feels like a tragedy.

I have a perpetual soft spot for both the Wolverine character and Jackman's portrayal. Wolverine is an individual that has endured countless examples of life's cruelties. In the comics, he was a pricklier, less sympathetic presence, but Jackman brought out Wolverine's emotional underbelly, emphasizing the tragedy that defined the character. He's a man who never wanted to have human connections, but was incapable of not becoming emotionally involved. Now he's left to care for the father figure of the family of mutants of which he only reluctantly became a part. Until his test-tubed created daughter Laura (complete with heightened healing ability and her own metal claws) appears on the scene, only the helpless Charles keeps him tethered to the world, because he's actively worked to not form attachments. Logan will always fight for those about whom he cares, and in the film's final moments Laura provides him with something Charles wanted him to have: a reason to fight when submission would be so much easier.

But as the narrative makes clear, both Logan and Charles have blood on their hands. Earlier X-Men films devoted countless frames to Wolverine slashing and murdering with his claws, all in thrilling, bloodless, PG-13 approved fashion. In Logan, however, the violence feels painful and nasty. The film doesn't revel in the carnage, but it makes the viewer feel nearly as beaten down by it as its titular protagonist.

As I watched the film, two lines from previous Westerns drifted in and out of my consciousness. The first is quoted within the film: Shane 's "There's no living with a killing." Spoken as part of a eulogy over Logan's grave by the young girl left behind to grieve him, the film reinforces the theme that killing wears an individual down. Sometimes violence may be necessary, but it leaves emotional scars upon those forced to partake.

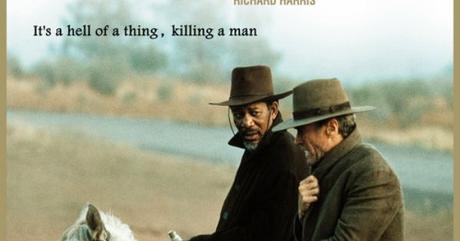

The other lines comes from Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven: "It's a hell of a thing, killing a man."

They're both from Westerns and they are both about the idea that taking a life, no matter the cause, changes the individual. Later in the film, Logan and Laura discuss the deaths they've caused. Laura reminds him, "I hurt people, too. Bad people." All he can do is bestow the knowledge that comes with having lived with violence for too long: that no matter who you kill, it's "all the same."

Thus, Logan is ultimately a film about loss, death, and the need to form emotional attachments. Of course, none of this would work if the performances weren't up to the task. Jackman has played Wolverine for so long, he could probably do so in his sleep, but he's always completely committed himself to breathing life into a character who should seem ridiculous onscreen. Throughout every fight scene and every utterance of the word "Bub," he has kept Logan's damaged, vulnerable humanity front and center. It's always been the case that the most invulnerable mutant was the most in danger of psychological trauma, and he made us feel that.

Here, he ensures we feel Logan's grief over his past and the fear of connecting to someone else. His gradual bond with Laura (so perfectly played by young newcomer Dafne Keen) and his frustrated devotion to Xavier make the film both a father/ son and father/ daughter drama. Logan doesn't realize he's forming attachments until, as he's nearing death, Laura holds his hand and sheds tears over his passing. "So that's what it feels like," he mutters. He also reminds her that she doesn't have to follow his path, that she can be better than the circumstances for which she was created. She doesn't have to be a killer, saying "don't be what they made you." There's something about these final lines that are more heart-breaking and more powerful than a movie like this has any right to be. They are both formed from abuse and tragedy, but Logan has been able to move beyond it, and he wants the same for Laura. You feel the sincerity and quiet heartbreak of that exchange with every ounce of your being.

It's no surprise that Patrick Stewart is a brilliant actor, and he clearly relishes the chance to play a disease-ravaged Xavier. He rants and weeps like the King Lear we all know he'll eventually play onstage to breathtaking effect. Xavier has often been a character I liked but to whom I had no real emotional attachment. He's heartbreaking here, because he has just enough awareness to realize his control is slipping away. That's a palpable, relatable fear for anyone as they age. When he insists Logan take Laura as they flee the antagonists trying to hunt her down (resulting in perhaps the most perfect road trip trio ever), he speaks of her with a childlike desperation of someone who doesn't fully grasp the ramifications of his situation. It's just a beautiful bit of acting.

There's also this perfect moment in which, following a dinner with a family who allows them to stay the night (RIP all three of them), in which Charles realizes he's responsible for the deaths of the students he always promised to protect.

"This has been the most perfect sleep I've had in years...and I don't deserve it, do I," he says despairingly. He's losing control of his abilities, fearing what awaits him, and trying to help Logan recognize his newly discovered offspring is a final chance at peace and familial affection. With the three central performances, the film becomes about a makeshift family, attempting to find a peace they may not entirely deserve.

Why was Logan capable of being this kind of film when so many other comic book movies aren't? Other comic book movies have made us cry, but this is a whole new level of emotional devastation. The answer is simple: Logan is a complete story, with no set up for a future installment. Like The Dark Knight Rises, it's about closing a loop on an individual's narrative, and both are about the burden that accompanies being the man who has to fight against the monsters. It's safe to say that this is the film I needed to remind me that a "comic book movie" can be a deep and thoughtful as the director and cast is willing to take it, and if it made you cry don't feel ashamed. That's what you're supposed to do at a movie which lingers in heartbreak the way Logan does.