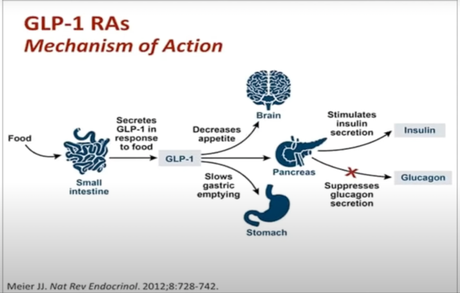

Semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) is part of a class of drugs that mimic the action of the peptide GLP-1, a hormone that’s secreted from the small intestine in response to food.

GLP-1 and drugs that mimic it’s actions like the ‘glutides’ have many actions throughout the body, but the most important direct effects are thought to be on the brain, pancreas and stomach.

The ‘glutides’ were originally developed as treatments for Type II diabetes. By decreasing appetite and slowing digestion they attenuate the amount of glucose entering the bloodstream. And by increasing insulin secretion and decreasing glucagon, they help get excess glucose out of the bloodstream.

In 2014, the FDA approved Liraglutide (Saxenda/Victoza) to treat obesity in adults. In 2021, Semaglutide was similarly approved. Semaglutide is preferable to some patients, because it only requires weekly injections compared with liraglutide’s daily ones.

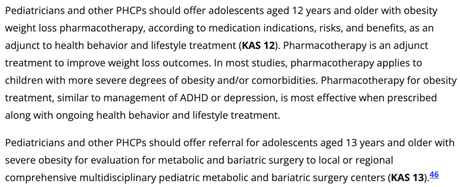

Recently, these drugs are in the news, in part, because in January of this year (2023) semaglutide joined liraglutide as FDA-approved for treating obesity in children 12 and older. A week later, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a Clinical Practice Guideline to the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity, which includes a section on pharmacotherapy (drugs) for treating obesity:

The AAP didn’t single out the glutted drugs, but of those listed, the glottides and orlistat are the only that have ben approved for long-term use in children with typical obesity, and the AAP points out that patients don’t like taking orlistat because it causes fatty stools, flatulence, and the runs.

So who is the AAP recommending doctors offer glottides to? The same group studied in clinical trials, kids 12+ with a BMI above the 95th percentile. But confusingly, this doesn’t mean the fattest 5% of kids, but rather the top 20%.

What is considered a obese is determined differently for children and adults. Whereas the threshold for obesity is defined as 30kg/m2 in adults, in children it’s set at the 95% percentile — according to historical data of children’s weights from 1963 to the early 1990s (a period when overall children were less likely to be overweight).

Today around 20% of children are considered obese by this metric. Another way of saying that is children are 4x as likely to be obese today, than they were in 1980.

And so when we say that semaglutide is approved for children with a BMI at the 95 percentile, we really mean 20% of children today. And while pediatricians are being recommended to offer that drug, that doesn’t mean that it is recommended for 20% of children, but rather the AAP is recommending that doctors initiate a conversation about the drug with their patients and let the patients and their families decide if the benefits outweigh the risks and unknowns.

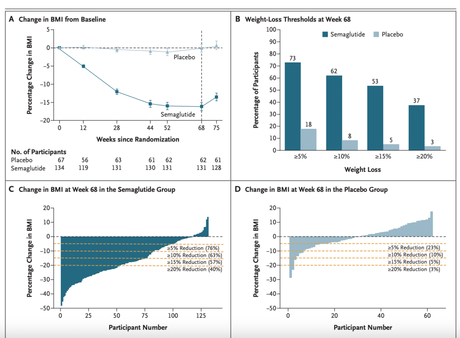

Semaglutide does appear effective at helping certain children lose weight. The clinical trial that led to its approval, used children with a mean age of 15 and a mean BMI of 37 that had failed at least one attempt to lose weight in the past. (So the average child in that study is literally of the chart shown above.)

Those patients lost −16.7% of their BMI compared to controls. While that’s huge, it’s important to note that weightless appears to plateau around 44 weeks and even after this treatment, that on average these patients would still be considered obese, with a BMI of around 31. How effective the drugs will be for patients with lower BMI remains to be seen.

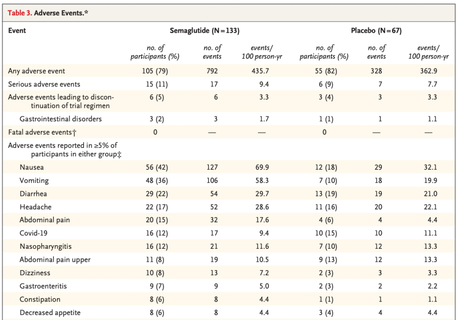

The main side effects for the ‘glutides’ are gastrointestinal, like nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, but also generally mild.

However, the FDA has placed a black box warning on the drugs for risk of certain cancers, because rats treated with the drugs had higher rates of thyroid and pancreatic cancers.

he FDA recommends against using them in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cell cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2a or 2b.

Overall, these drugs seem useful for treating extreme obesity but they are far from magic bullets. The truth about obesity is that once pathological processes start, they are very hard to permanently reverse through lifestyle modification, psychotherapy, or even bariatric surgery.

The best bet for solving the obesity crisis is preventing obesity from occurring in the first place. Obesity emerged as a crisis in the 20th century, alongside changes to our environment like the widespread availability of cheap healthy food, and changes to our culture around food and exercise. Solving the crisis will require us to reverse these changes, as messaging and education around healthy lifestyles have proved ineffective.

But perhaps drugs like the ‘glutides’ can ameliorate some negative health effects in children and adults who’re already obese.

Advertisement