Not at all what David thinks.

I have to say I was a bit amused to read David Brooks’ most recent column from the comfortable couch of our two-bedroom apartment rental overlooking a harbor in Cornwall, England. You see, David is a bit confused about the emerging “peer-to-peer” economy. To his credit, he admits as much.

I’m one of those people who thought Airbnb would never work. I thought people would never rent out space in their homes to near strangers. But I was clearly wrong.”

He then tries to explain why his original prediction failed, only to demonstrate that he still doesn’t really get what’s going on.

On the one hand, he does seem to grasp the way in which new technologies are rendering rigid old structures flexible. On the other, he seems completely oblivious to the value such flexibility provides. It’s a theme that runs throughout the piece.

I’ll hazard a guess that his blind spot comes from a political philosophy that prefers to see people constricted in various ways. He may not realize it, but that isn’t what most people want. People really do value having options. That simple understanding would, I think, have made everything clear to him.

But for our purposes, let us start at the beginning.

First, I underestimated the effects of middle-class stagnation. With wages flat and families squeezed, many people have to return to the boardinghouse model of yesteryear. They have to rent out rooms to cover their mortgage or rent.”

This is a story that sounds plausible and follows a narrative that probably fits nicely within the New York Times opinion pages, but it doesn’t really hold up to scrutiny. Sure, there are undoubtedly people who are doing exactly what David describes, but hard-pressed homeowners aren’t the primary suppliers of Airbnb properties. All you have to do is look at the kind of spaces available to rent and that much becomes clear.

In midtown Manhattan, for example, a quick search pulled up 312 listings for entire homes, 166 for spare rooms in an occupied home and 36 for shared rooms. In other words, more than 60% of the listings were for spaces that are indistinguishable from vacation rental properties. We found the same thing in Paris, where a whopping 86% of listings were for entire homes. Clearly people renting out spare rooms to make ends meet aren’t the majority of Airbnb hosts.

So who are they?

From our experience Airbnb hosts are an extremely diverse group. Some are professional investors who manage multiple properties. That’s the case with the rental I’m currently typing from, where I don’t expect to ever meet the owner. Other people have converted their houses into basic bed-and-breakfast type hotels.

We’ve stayed in apartments made vacant because the owner moved in with their significant other. We’ve seen properties come on the market specifically for special events, like the Super Bowl, when demand and hotel prices are exceptionally high. We’ve also seen people using Airbnb to lease their space while they’re away on vacation. And yes, sometimes we’ve stayed in apartments temporarily vacated by young owners (or likely renters) looking for some easy cash.

None of these situations smack of “middle-class stagnation.” If I had to choose a word to describe the Airbnb phenomenon I’d say “opportunism” fits best. What we’re seeing in its success are people seizing these opportunities for various reasons.

To appreciate why people are listing their properties on sites like Airbnb you have to understand how cumbersome residential real estate is for those who own it. It’s a huge investment that is both costly and time consuming to monetize. If you want to sell your property you can expect to spend months courting potential buyers, pay hundreds or thousands of dollars in legal fees, and hand over an outrageously large 5% fixed commission to a real estate broker.

And that costly option is only available if you want to sell the entire property. What do you do if you happen to own 20% more house than you really want? The old answer was to sell the whole thing, buy something else, and incur all those costs on both ends of the trade. That’s great for real estate professionals but horrible for you.

Now you have other options. If you still want to sell your property you can at least recoup some of the costs by renting it short-term while you search for a buyer – we stayed in one such property. You might decide to turn your empty nest into a B&B. You could lease it for the winter while you snow-bird down south. Or maybe you decide to “downsize” by converting the entire big old house into an investment property while you move into a smaller one.

Whatever you decide, you now have a bunch of options you didn’t really have before.

Second, I underestimated the power that liberal arts majors would have on the economy. Millions of people have finished college with a hunger for travel and local contact, but without much money. They would rather stay in spare rooms in residential neighborhoods than in homogenized hotels in commercial areas, especially if they get to have breakfast with the hosts in the morning.”

Leaving aside the fact that any service allowing travelers to avoid “homogenized hotels in commercial areas” is of tremendous value all by itself, David clearly misunderstands the scope of what Airbnb offers.

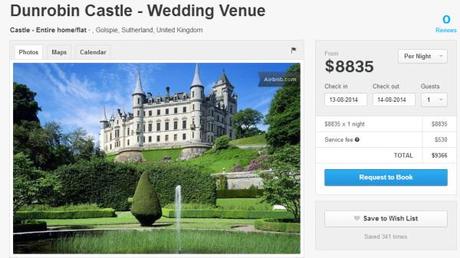

Perhaps I can interest you in this humble castle for a mere $8,800 per night? I’d love to offer you this more modest beach house in The Hamptons for $825 per night, but I’m sorry to tell you that it’s fully booked for the season.

David’s assumption that those of us who utilize “house-sharing” services are too poor to afford traditional hotels is not his biggest misunderstanding. That distinction goes to his implied presumption that typical hotel accommodations are necessarily more expensive and more desirable than Airbnb rentals. They are neither.

Hotels serve their purpose, and we still use them quite extensively. But they often leave a lot to be desired, especially for longer stays. The fact that we didn’t have to run out this morning in the rain to procure a cup of coffee is a huge amenity for us. As is the dinner I’m going to cook tonight that is both more delicious and more nutritious than any restaurant meal we’ll find nearby.

Sorry, this $825 per night house in The Hamptons is fully booked for August.

Before Airbnb these kinds of properties were difficult, if not impossible, to come by. When I contacted a New York City area real estate agent to ask about renting an apartment for three weeks this past spring, I never got a reply. And this was from someone with whom we had years of business dealings. He just completely blew us off because you generally can’t rent apartments in New York City for three weeks. Such short-term rentals don’t exist.

Well, they didn’t really exist before, but they do now. After being ignored by the city’s real estate professionals, we had little difficulty finding and renting a fully furnished studio apartment in a Brooklyn brownstone through HomeAway.com.

Just as house-sharing sites create new options for property owners, they also create new options for renters. The fact is that traditional hospitality offerings don’t always meet our needs. Having a huge inventory of short-term apartment rentals to choose from helps plug that hole.

Socially, we have large numbers of people living loose unstructured lives, mostly in the 10 years after leaving college and in the 10 years after retirement.

These people often live alone or with short-time roommates, outside big institutional structures, like universities, corporations or the settled living of family life. They become very fast and fluid in how they make social connections. They become accustomed to instant intimacy, or at least fast pseudo-intimacy. People are both hungrier for human contact and more tolerant of easy-come-easy-go fluid relationships.”

David gets closest to the truth here in everything but tone. His disapproval is palpable. But where he sees “loose unstructured lives” I see people tailoring lifestyles in a way that best suits them.

Unbound by “big institutional structures” people are increasingly able to make a living where they want, when they want and how they want. That fact allows us to spend 365 days a year traveling – working from our rented apartment in Cornwall when it suits us, or when it’s raining, or when we’re inspired, rather than when the calendar and clock on the wall say we must.

And our easy-come-easy go relationship with employers lets us pursue multiple careers over the course of a lifetime. We’re no longer bound to a job or a company we chose at the tender age of 18, long before we really knew anything about the world, let alone about ourselves. I figure I’m currently living the fifth or sixth distinct chapter in my life. I expect I’ll write at least as many more before I’m done.

Along the way I’ll meet plenty of people. Some will become fast friends while others I’ll soon forget, or at least hope to. But through all of that I’ll find no deeper or lasting intimacy than with the person I now spend every moment of my life with. The kind of togetherness Shannon and I share was not generally possible two decades ago. It’s made possible today by the same forces that give rise to the “pseudo-intimacy” of our more fluid relationships.

Like everything else in today’s world, where and when and whether we cultivate these deep and meaningful relationships is a choice. It’s not something forced on us by a society that says we have to settle down and raise a family the moment our bodies indicate we’ve become adults.

We have more options today than we’ve ever had before. And that sounds like progress to me.