Chimps have a special place in our culture as “stand ins” for our early ancestors. The classic ascent of man image depicts us evolving upwards from a knuckle walking creature, whilst scientists use chimps when they want to research the behavior of our ancestors. However an increasing amount of evidence suggests that our lineage differed from chimps in several key ways; including how we move. It would seem that our lineage never knuckle walked like a chimp (Lovejoy and McCollum, 2010).

The Australopithecines emerged around 4 million years ago and were the first adept bipeds in our family. However, their skeleton contains no evidence of them being an ex-knuckle walker (Marze, 1986). Roll the clock back even further to Ardipithecus ramidus, who lived around 4.4 million years ago and even though they were that skilled at walking upright there is still no evidence of them walking on their hands like a chimp (Lovejoy et al., 2009).

So if our ancestors didn’t knuckle walk before they became bipedal, how did we move before we started walking upright? Two different ideas have emerged.

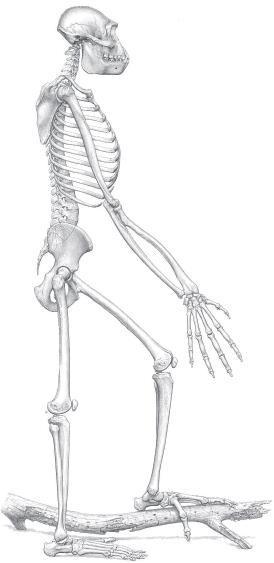

Ardipithecus ramidus walking along a branch (the left foot), showing a possible origin of terrestrial bipedalism (the right foot)

The first suggests that bipedalism evolved as a way of walking across branches, allowing our ancestors to traverse the jungle with the greatest of ease. Evidence for this hypothesis comes from the aforementioned Ardipithecus ramidus. This species had some bipedal ability, yet still lived in the trees, suggesting that walking upright did in fact evolve as a means of traveling around the tree tops (Lovejoy et al., 2009).

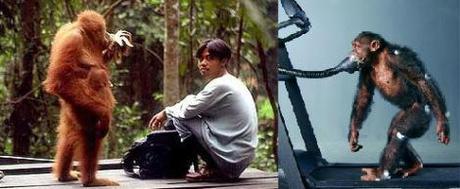

The alternative hypothesis argues bipedalism evolved from swinging through the trees (like an orang-utan). Dangling below the trees like this resulted in a vertical body well suited for bipedalism; biasing our evolution in that direction when it came time for us to move on the ground. Evidence for this idea comes from apes that lived before the chimp and human families split 7 million years ago. Researchers noted that the earlier apes which swung from the trees are those with these vertical bodies. Further, the only living ape that swings from the trees is also the best at walking upright (apart from us).

An upright orang-utan showing off just how much better at bipedalism it is than a hunched over chimp

Although both ideas had a fair bit of evidence supporting them, neither could gather enough to demonstrate that it was the correct answer. However, all of this changed when scientists re-examined Oreopithecus, an European ape that lived in the swampy jungles of Italy 9 million years ago (back when Italy had swampy jungles). Oreopithecus is important to this debate because it appears to have swung through the trees, yet was also a relatively good biped. In other words, it indicates that bipedalism did emerge from swinging through the trees, confirming the “swinging-as-a-precursor-to-bipedalism” hypothesis (Kohler et al., 1997).

Oreopithecus

Or at least, it did until last week. New research has just been published that re-re-examines Oreopithecus and finds little evidence for bipdealism in the species. The key piece of evidence for upright walking originally cited was a curve in the lower back, known as lumbar lordosis. Humans have it too; you can feel it if you stand up and trace the bottom half of your spine. This curve helps keep the center of gravity where it should be so we don’t topple over.

People thought Oreopithecus also had it, but this new research reveals that it actually doesn’t. There is distortion in the fossil which makes it look like the back is curved; but when this distortion is taken into account the lumbar lordosis disappears (Russo and Shapiro, 2013). This may seem like a fairly basic error to make but remember, it has happened before. Examining skeletons that have been buried for millions of years is a tricky business and sometimes mistakes are made.

And without Oreopithecus the biped we’re back to square one, with no way to tell if bipedalism arose as a result of walking on branches or dangling below them. It would seem that the origins of bipedalism are as mysterious as ever.

References

Köhler, Meike; Moyà-Solà, Salvador. (1997). Ape-like or hominid-like? “Ape-like or hominid-like? The positional behavior of Oreopithecus bambolii reconsidered” . PNAS94 (21): 11747–11750

Lovejoy, C. O., Suwa, G., Spurlock, L., Asfaw, B., & White, T. D. (2009). The pelvis and femur of Ardipithecus ramidus: the emergence of upright walking.Science, 326(5949), 71-71e6.

Lovejoy CO, & McCollum MA (2010). Spinopelvic pathways to bipedality: why no hominids ever relied on a bent-hip-bent-knee gait. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 365 (1556), 3289-99

Marzke, M. W. (1983). Joint functions and grips of the Australopithecus afarensis hand, with special reference to the region of the capitate. Journal of Human Evolution, 12(2), 197-211.

Russo, G. A., & Shapiro, L. J. (2013). Reevaluation of the lumbosacral region of Oreopithecus bambolii. Journal of Human Evolution.