Beyond that amazing hair, though, is the brain damage that's been causing us so much trouble since birth. Of course, every baby goes through a stage when they don't seem to advance for ages; but when Isobel has periods of developmental inactivity, we can't stop wondering if that is a sign of her CP becoming more pronounced. I certainly think that her signing skills might be regressing at the moment.

Come end of December, Isobel will have reached 18 months, at which she is to have the MRI scan that will determine the severity and likely prognosis of her disability. Although not a horrific prospect, we are nevertheless primed for it.

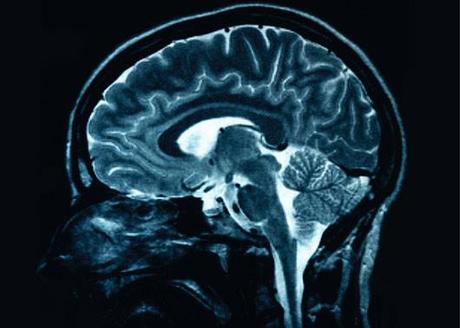

The human brain is a marvelous thing, packed full of intricacies that scientists don't quite understand. For that reason, it is also capable of nasty surprises. Given the power our brains give us over the rest of the animal kingdom, that no computer can emulate its unknown quantities is perhaps a good thing.

I can't stress enough how pivotal that MRI scan is. Brain injury is like a splodge in the cerebellum; no two splodges are quite the same. Although, of course, cerebral palsy is just one consequence of a brain injury, it is nevertheless a huge umbrella term - with many variations even within its four main types - which explains why it is so hard to predict and takes so long to conclude.

Whatever happens to a baby with suspected cerebral palsy physically does not always echo the reality lurking within her brain. Whatever happens in her MRI scan at 12 months won't be the same at 18 months. That age is when the disability first becomes established, although the standard infant developmental timeline won't be complete until age three.

When Isobel's CP was first identified at 11 1/2 months, I was struck by her paediatrician's reticence. Not until she attended physio and I spoke to Helen the next day did I understand that she had received a diagnosis. Dr Mallya just didn't want me to take it as gospel, because his conclusions were based on a physical examination of her facilities. Indeed the most confident description he could give was that she had a motor developmental disorder.

Babies use 80% of their brain capacity by the time they're four. After that, it's reduced to 10%. Why? I dream every night of finding out, so I can be sure that Isobel has maximised hers by 2013.

The deaf mentor who said that the internet was our best friend was right. Ever since I first suspected delays in Isobel's development, I have been subscribing to a free online forum called the BabyCentre Community. This has a range of themed discussion boards that you can join and post messages to. Many mums use them to let off steam, pass on useful links and information, and ask for help and mutual support.

The two boards I read the most regularly are, naturally, 'Cerebral Palsy' and 'Special Needs Children.' Run by mums to disabled children for other mums like themselves, their common bond is their wish to share experiences of medical procedures, developmental activity (or lack of), and other causes for happiness or sadness with people who they know will empathise. Because these two boards are where you will probably find some of the most profound expressions of fear, depression, grief, anxiety, joy, frustration, and anger, they give me clear reassurance that I am not mad and certainly not alone.

It was through reading a post by one particularly distressed woman on one of these boards that the significance of MRI scans really hit home. Her daughter had just had her second scan and it'd revealed that her brain damage was far more widespread than her first scan at 10 days old had suggested. She was told not to expect much more development from her.

Naturally, she was so traumatised that she couldn't take in the new information, and my heart went out to her. Like Isobel, she had microcephaly (a smaller than average head circumference, with a slower rate of growth) - which bothered me a little, although Isobel's is not as obvious, partly due to that abundant hair.

But of course, every baby is an individual, and that this sweet little girl appears to have had her MRI scan at 12 months is a crucial difference. Her impairment may be more noticeable, but that's not to eliminate the possibility that she could still defy her doctors.

Once again, it boils down to the extraordinary and inexplicable capabilities of the human brain. How otherwise is Isobel able to twirl her hair with her fingers?

I don't anticipate quite so much of a shock from her forthcoming scan, appointment details of which are yet to be confirmed. My impression is that given her age, it is more likely to expand on the conclusions drawn from her physical examination at 11 1/2 months and other assessments since then, with hopefully more clarity in relation to her cognitive and mental abilities.

Even so, I view it with extreme trepidation. Hope for the best, prepare for the worst.