Their association began when Marie Theresa asked the Count Mercy to approach Marie Antoinette to request two full length portraits for a room filled with family portraits.

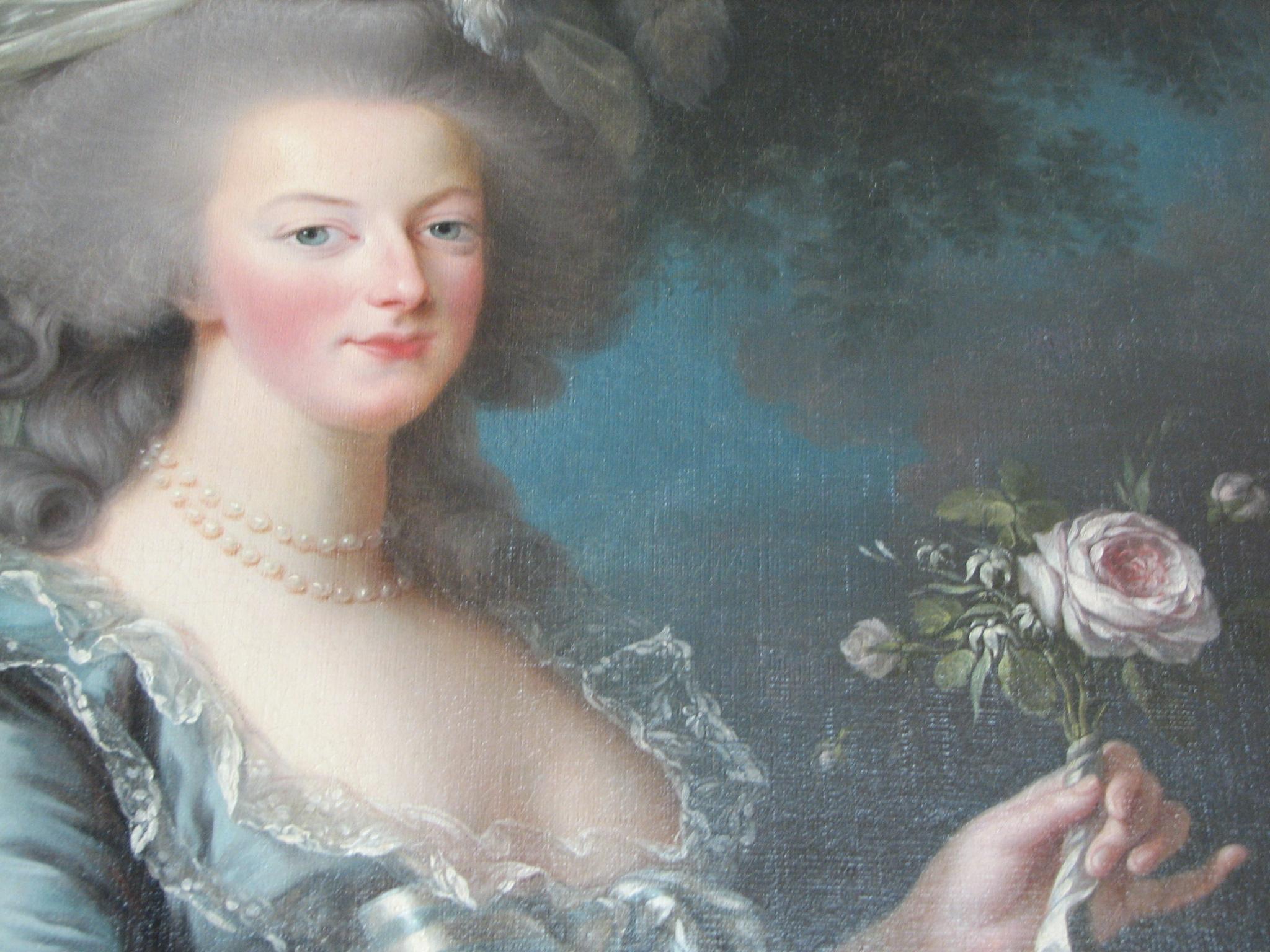

Forgoing the usual court painters, Marie Antoinette chose someone new for this important commission: a rising star in art, the Parisian portraitist Madame Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, who had already painted Marie Antoinette’s brother in law, the Comte de Provence. It was to be the first painting in a series that was to immortalise both sitter and artist in the eyes of posterity: when one thinks of Marie Antoinette, it is the vision of her as painted by Madame Vigée-Lebrun that one usually sees, either dressed in shimmering white silk as here, radiant in blue silk and holding a rose in the gardens of the Petit Trianon, shyly smiling in soft white muslin or holding her precious children close while surrounded by the splendours of Versailles.

The first of the paintings, the one above, was sent in January 1779 and the Empress immediately fired off a letter saying how delighted she was with it and Marie Antoinette liked it so much that she ordered another copy to be hung in her rooms at Versailles.

It was in the year 1779 that I painted the Queen for the first time; she was then in the heyday of her youth and beauty. Marie Antoinette was tall and admirably built, being somewhat stout, but not excessively so. Her arms were superb, her hands small and perfectly formed, and her feet charming. She had the best walk of any woman in France, carrying her head erect with a dignity that stamped her queen in the midst of her whole court, her majestic mien, however, not in the least diminishing the sweetness and amiability of her face. To any one who has not seen the Queen it is difficult to get an idea of all the graces and all the nobility combined in her person. Her features were not regular; she had inherited that long and narrow oval peculiar to the Austrian nation. Her eyes were not large; in color they were almost blue, and they were at the same time merry and kind. Her nose was slender and pretty, and her mouth not too large, though her lips were rather thick. But the most remarkable thing about her face was the splendour of her complexion. I never have seen one so brilliant, and brilliant is the word, for her skin was so transparent that it bore no umber in the painting. Neither could I render the real effect of it as I wished. I had no colours to paint such freshness, such delicate tints, which were hers alone, and which I had never seen in any other woman.

Marie Antoinette was painted several times by a wide variety of different artists, but none managed to capture her essential charm and freshness as well as Vigée-Lebrun. Yes, her portraits do err on the side of flattery and I am a bit doubtful about her ability to actually capture a proper likeness but her portraits of Marie Antoinette are imbued with something else that is much more compelling – they speak volumes about the young Queen’s shyness, her levity, the radiance of her complexion and the animated grace with which she carried herself at all times. It is when I look at the portraits that Vigée-Lebrun painted of Marie Antoinette in the years leading up to the French Revolution that I truly mourn the passing of this decadent, beautiful, frivolous age.

At the first sitting the imposing air of the Queen at first frightened me greatly, but Her Majesty spoke to me so graciously that my fear was soon dissipated. It was on that occasion that I began the picture representing her with a large basket, wearing a satin dress, and holding a rose in her hand. This portrait was destined for her brother, Emperor Joseph II., and the Queen ordered two copies besides – one for the Empress of Russia, the other for her own apartments at Versailles or Fontainebleau.

I painted various pictures of the Queen at different times. In one I did her to the knees, in a pale orange-red dress, standing before a table on which she was arranging some flowers in a vase. It may be well imagined that I preferred to paint her in a plain gown and especially without a wide hoopskirt. She usually gave these portraits to her friends or to foreign diplomatic envoys. One of them shows her with a straw hat on, and a white muslin dress, whose sleeves are turned up, though quite neatly. When this work was exhibited at the Salon, malignant folk did not fail to make the remark that the Queen had been painted in her chemise, for we were then in 1786, and calumny was already busy concerning her. Yet in spite of all this the portraits were very successful.

I was so fortunate as to be on very pleasant terms with the Queen. When she heard that I had something of a voice we rarely had a sitting without singing some duets by Grétry together, for she was exceedingly fond of music, although she did not sing very true. As for her conversation, it would be difficult for me to convey all its charm, all its affability. I do not think that Queen Marie Antoinette ever missed an opportunity of saying some thing pleasant to those who had the honor of being presented to her, and the kindness she always bestowed upon me has ever been one of my sweetest memories.

This 1783 portrait depicts the 27 year old Queen of France in her favorite outfit, a simple ruffled muslin gown, tied at the waist with a gauze sash and teamed with a ribbon bedecked straw hat. She is posed as though picking roses in her beloved gardens at the Petit Trianon and her gaze is both direct and enquiring, although not unfriendly.

This painting caused a sensation when it was displayed at the prestigious Paris Salon of 1783. Marie Antoinette and Madame Vigée-Lebrun, both young women whose minds were full of romance and idealistic ideas of the simplicity and virtue of private life were fixated on the lack of etiquette in the painting, in the lack of heavy court gowns and jewels, in its charm and honesty. The critics and populace at large, however were rather less charmed and saw in the lack of Queenly decoration and etiquette, a quite deplorable lesé majesté that acted as a metaphor for the gradual erosion of the dignity of both France and its royal family.

One day I happened to miss the appointment she had given me for a sitting; I had suddenly become unwell. The next day I hastened to Versailles to offer my excuses. The Queen was not expecting me; she had had her horses harnessed to go out driving, and her carriage was the first thing I saw on entering the palace yard. I nevertheless went upstairs to speak with the chamberlains on duty. One of them, M. Campan, received me with a stiff and haughty manner, and bellowed at me in his stentorian voice, “It was yesterday, madame, that Her Majesty expected you, and I am very sure she is going out driving, and I am very sure she will give you no sitting to-day!” Upon my reply that I had simply come to take Her Majesty’s orders for another day, he went to the Queen, who at once had me conducted to her room. She was finishing her toilet, and was holding a book in her hand, hearing her daughter repeat a lesson. My heart was beating violently, for I knew that I was in the wrong. But the Queen looked up at me and said most amiably, “I was waiting for you all the morning yesterday; what happened to you?”

“I am sorry to say, Your Majesty,” I replied, “I was so ill that I was unable to comply with Your Majesty’s commands. I am here to receive more now, and then I will immediately retire.”

“No, no! Do not go!” exclaimed the Queen. “I do not want you to have made your journey for nothing!” She revoked the order for her carriage and gave me a sitting. I remember that, in my confusion and my eagerness to make a fitting response to her kind words, I opened my paint-box so excitedly that I spilled my brushes on the floor. I stooped down to pick them up. “Never mind, never mind,” said the Queen, and, for aught I could say, she insisted on gathering them all up herself.

When the Queen went for the last time to Fontainebleau, where the court, according to custom, was to appear in full gala, I repaired there to enjoy that spectacle. I saw the Queen in her grandest dress; she was covered with diamonds, and as the brilliant sunshine fell upon her she seemed to me nothing short of dazzling. Her head, erect on her beautiful Greek neck, lent her as she walked such an imposing, such a majestic air, that one seemed to see a goddess in the midst of her nymphs. During the first sitting I had with Her Majesty after this occasion I took the liberty of mentioning the impression she had made upon me, and of saying to the Queen how the carriage of her head added to the nobility of her bearing. She answered in a jesting tone, “If I were not Queen they would say I looked insolent, would they not?”

The last sitting I had with Her Majesty was given me at Trianon, where I did her hair for the large picture in which she appeared with her children. After doing the Queen’s hair, as well as separate studies of the Dauphin, Madame Royale, and the Duke de Normandie, I busied myself with my picture, to which I attached great importance, and I had it ready for the Salon of 1788. The frame, which had been taken there alone, was enough to evoke a thousand malicious remarks. “That’s how the money goes,” they said, and a number of other things which seemed to me the bitterest comments. At last I sent my picture, but I could not muster up the courage to follow it and find out what its fate was to be, so afraid was I that it would be badly received by the public. In fact, I became quite ill with fright. I shut myself in my room, and there I was, praying to the Lord for the success of my “Royal Family,” when my brother and a host of friends burst in to tell me that my picture had met with universal acclaim. After the Salon, the King, having had the picture transferred to Versailles, M. d’Angevilliers, then minister of the fine arts and director of royal residences, presented me to His Majesty. Louis XVI. vouchsafed to talk to me at some length and to tell me that he was very much pleased. Then he added, still looking at my work, “I know nothing about painting, but you make me like it.”

The picture was placed in one of the rooms at Versailles, and the Queen passed it going to mass and returning. After the death of the Dauphin, which occurred early in the year 1789, the sight of this picture reminded her so keenly of the cruel loss she had suffered that she could not go through the room without shedding tears. She then ordered M. d’Angevilliers to have the picture taken away, but with her usual consideration she informed me of the fact as well, apprising me of her motive for the removal. It is really to the Queen’s sensitiveness that I owed the preservation of my picture, for the fishwives who soon afterward came to Versailles for Their Majesties would certainly have destroyed it, as they did the Queen’s bed, which was ruthlessly torn apart.

This is one of the most iconic portraits of Marie Antoinette and depicts her surrounded by her children in one of the ante rooms at the end of the Hall of Mirrors. The painting was originally intended to show four children – Madame Royale, the Dauphin Louis, the toddler Louis-Charles and finally the baby, Sophie-Béatrix. Sadly, Madame Sophie died before the painting could be completed and instead her blue cradle is empty. This portrait was painted in 1787, when the Queen was 32 years old and very different to the frivolous girl of Vigée-Lebrun’s earlier portraits. As she entered her thirties, Marie Antoinette renounced the flounces and furbelows of her youth and instead adopted a more grown up and dignified style, as evidenced here by her rich crimson velvet gown, which is so different to the light gauzes and satins of before.

By 1787, the once wildly popular Queen of France’s reputation was in tatters and it seemed as though she could do nothing right – in retaliation she retreated ever further away from both the court and wider public life, preferring instead to spend most of her time at the Petit Trianon with her closest friends and children. This painting was originally concieved to repair the Queen’s reputation in France by depicting her as an ‘ordinary’ mother, more concerned with her children than fashion.

Everything about this painting is very carefully calculated to both enhance and promote Marie Antoinette, from her rich but plain dress, to her direct and unapologetic gaze to the triangular grouping which is so reminiscent of paintings of the holy family. The message is clear – we are in the presence of a Queen who is foremost a mother, not just to her own children but also to her people.

My book The Secret Diary of a Princess: a novel of Marie Antoinette is currently £1.16 from The Secret Diary of a Princess: a novel of Marie Antoinette and $1.78 from Amazon US.