My experience using political cartoons when teaching political or cultural history has been that when I find a drawing that is apropos for college students, it garners little if any reaction from the students. It makes me wonder, how many of the students actually understand the cartoon and what the artist is suggesting in its rendering? An article in Journalism Quarterly from 1968 probably answers my question—and the answer is a resounding—NO.

According to author Leroy Carl, only 15% of Americans understand the artist’s intended message, and another 15% of Americans partially understand the artist’s message. That leaves 70% of Americans in the dark. What that means is in a classroom the teacher is enlightening 15% of his/her students, confusing 15%, and frustrating 70% unless there is a way of teaching students how to better understand political cartoons.

Teaching how to better understand editorial cartoons presumes that the understanding of cartoons is not inherent (kind of like learning perfect pitch—you either have it or you don’t). If it is not inherent, how does one go about teaching it? On-line resources on how to teach political cartoons are pitching someone’s teaching resources more than explaining a process– except for an article by Jonathan Burack, a former history instructor and editor of Newscurrents. The problem with Burack’s system, found at http://teachinghistory.org/teaching-materials/teaching-guides/21733, is that it assumes students know too much.

The first things that students must identify is from the journalistic dictum of who, what, where, and when. After all, cartoons are journalistic opinions. After that, one can either use Burack’s system of analyzing “symbol and metaphor,” visual distortion, “irony in words and images,” “and stereotype and caricature,” but how many college frosh can pick out an irony—in anything? I suggest that there are two more steps: Many cartoons either make comparisons or exaggerate (or understate) a concept, or both. Ask students to identify the humorous effect that the artist is using—even if the cartoon is not humorous. Eventually, students should get to the “why” in the cartoon. Why is this important? What is the artist’s intended message? Finally, discuss whether the cartoon is fair to the subject.

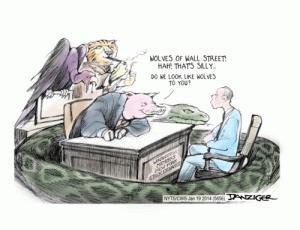

Consider the following cartoon by Jeff Danziger and dated on January 19, 2014:

Who: Wall Street Bankers and investors

What: New York Stock Exchange and the movie Wolves of Wall Street. Note the sign: “Warning: Members New York Stock Exchange.” The pig denies that any of the brokers in the office are wolves.

Where: A broker’s office (note that it is the home turf of the brokers).

When: 2014 (when using historical cartoons that may be more difficult to ascertain, and some contemporary cartoons are actually set at some time in the past for reasons of comparison).

Comparisons: The movie title compares stock brokers to wolves, a carnivorous predator. The cartoonist compares stock brokers to vultures, those who prey on carrion; tigers, another carnivorous predator; snakes, known for their “cold-blooded killing,” and their trickery as depicted in Genesis in the Bible; and pigs, stereotyped as sloppy-eaters that consume whatever they can get their mouths on.

Intended message: The artist suggests that labeling Wall Street brokers and bankers as wolves is an understatement. They also have the characteristics of vultures, tigers, snakes, and pigs.

At this point, much of Burack’s discussion can be incorporated: The man is trapped by the body of the snake. What the pig says is ironic in that he denies his and his partners’ “wolfishness.” Discuss “anthropomorphism.” Would this cartoon be as effective if a human were talking and the animals were described as his/her partners? Do most signs identifying an entity as a member of the New York Stock Exchange carry a warning?

Finally, from Burack’s lesson, is this a fair statement about bankers and brokers? Why or why not?

The question is whether understanding political cartoons and the depictions therein is actually teachable? If it is, is it a necessary skill? If not, what do teachers do with the wealth of political cartoons that are in history books? I am going to try teaching American History using political cartoons, and I would like my lessons to be effective. Therefore, I welcome helpful comments from readers of this blog.