Tell us about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humo r?

My original topic for my dissertation was a folkloric look at the tall tale as a genre, but that morphed into the tall tale as a form in antebellum American comic writing and an influence on Mark Twain. So, in my academic career, I have always been interested in cultural artifacts that make people laugh.

However, the real turning point was being selected in 1989 for a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar on humor held at Berkeley and run by an anthropologist, Stanley Brandes. Those six weeks converted me to an interdisciplinary point of view. I spent more time in Kroeber Library (the anthropology collection) than any other library on the campus, mostly being fascinated by ritual clowns in traditional societies (my earlier folklore penchant had turned into an anthropological one). I've tried to maintain an interdisciplinary approach ever since.

.

Tell me about the genesis and creation of this project. What questions did you set out to answer, and how did your project develop to answer them?The first impetus for the book came from submitting a proposal on satire to a projected collection of essays in the MLA teaching series. The proposal was rejected, but my interest in the topic had developed out of my Year's Work reviews for Studies in American Humor because over the years I had tracked a growing set of publications on satire. Satire in the first decade of the twenty-first century was becoming a hot topic, which meant that for some time prior to writing the book I was immersed in the scholarly conversation about satire.

The second push came from a comment Judith Lee made about an introductory essay I had written for a special issue of StAH on postmodern satire. In the essay, I referred to satire as a special kind of comic speech act, and with her usual perspicacity, Judith said that that idea could be expanded. The foundation work I had done for the rejected proposal was then turned to use for the book, and the introductory essay on postmodern satire became the first draft of parts of the book.

I wanted to understand satire as a postmodern project in some of the artists that I had been faithfully watching on TV or in comedy specials. The entanglement of contemporary satire with the news was always a stimulus to my thinking. I also wanted to address the issues surrounding satire that I had zeroed in on when I wrote the proposal for the MLA collection: satire's efficacy as a reform agent; satiric intent versus audience uptake; the importance of cultural context for understanding what the satirist intended and what the audience understood. I don't see how one can tackle satire and not become enmeshed in these issues, and I use the examples in the book to work through them.

.

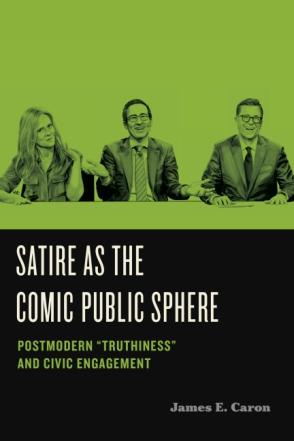

Your book-Satire as the Comic Public Sphere-develops a new approach to thinking about how satire, especially satire in the current media landscape, might operate. What do you hope that readers take from the book about how to understand satire?The approach is new in part because I use speech act theory as a heuristic for contemporary examples of satire that play with the news, so I hope others find that tactic useful. The news as a focal point for some satire, however, points to the big claim in the book: that the best way to think about satire since the Enlightenment is to understand its connection to Jürgen Habermas's concept, the public sphere. Satire parodies the public sphere and functions as its comic supplement. I think that framework makes sense, and I hope it persuades folks. Also, that framework enables understanding that satire functions as comic political speech, not political speech, which is how many scholars treat it. I suspect that there will be lots of resistance to that distinction, so I'll be interested how it is processed in future scholarship.

The idea of a "truthiness satire" in a postmodern aesthetic provides a way to think about the recent cultural moment in which people, in particular politicians, offer "alternative facts" as competition in the public sphere to evidence and empirical science. Some folks call the resulting situation "post-truth," but that misunderstands what has happened, implying that no one is interested in the truth any more, or that it can't be formulated in a meaningful way. That position is essentially a bastardization of postmodern skepticism, which questions transcendental claims for a Truth, but does not doubt that facts exist and should be marshalled in any public sphere debate. I refer to the dismissal of facts and evidence as the "anti-public sphere," and ridiculing it is the job of truthiness satire. The book is meant to demonstrate the poetics of that ridicule. I also probe the legitimate limits of that ridicule: when does the symbolic violence of satire descend into mere rants or screeds?

Finally, the first part of the book offers an extended definition of satire that is meant to be useful for other cultures besides American and for other time periods besides now. I hope that readers understand the dual goals of the book: one general and not time-specific, the other very time specific.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?Of course, what I really want is to alter forever the course of scholarly thinking about satire [ insert laughter here]. My hope is that the definition worked out in the first part of the book spurs some thinking about satire in general as well as satire's function in what some call "the project of modernity," which includes postmodernity.

For the book's second part, I hope that my examinations of contemporary satirists like Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, and John Oliver are persuasive, that demonstrating the dynamic relationship among the discourse of the public sphere, satire as discourse of the comic public sphere, and truthiness as the discourse of the anti-public sphere shows just how and why satire has become so prominent and so important in recent times.

My approach centers on the aesthetics of satire as well as its communicative force in the public sphere, but satire as a cultural artifact has an appeal across disciplines, including rhetorical theory, communication theory, political science and sociology as well as cultural studies, so I hope the book can contribute to conversations in those fields as well as humor studies. That would be in keeping with my original interdisciplinary interest in what makes people laugh.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?As a contributing editor and associate editor of StAH for about fifteen years, what I've seen is a huge and still growing interest in comic artifacts of all sorts by a wide range of disciplines. That has been exciting to witness and to be a part of.

The scholarly trend has moved away from a focus on literary comic artifacts to other media, especially film, TV, and standup. Gender studies and ethnic studies have also been growing in their influence. Earlier historical periods are somewhat overshadowed by examinations of the now and the recent past. The internet beckons as a largely unexplored territory: we are still trying to get a handle on humorous or satiric memes, for example.

I see the study of cultural artifacts that make people laugh as a growth area (to use market terms) for some time to come. The variety of disciplines that are investigating those artifacts is wonderful, and I don't envision that letting up. There are now several journals devoted exclusively to scholarship on comic artifacts, and I would not be surprised if others showed up in the future. Moreover, there is still much work that can be done in earlier historical periods. Just trying to keep up with recent artistic production will provide work for many scholars as we conduct our various kinds of research across disciplines.

I have another book project centered on satire, partly finished. (I seem to be stuck to satire as though it were a tar baby, though I am not complaining.) My research question: what did satire in the US look like before Mark Twain came along and altered everything? There is a long tradition in the scholarship on American humor in the nineteenth century that sees everything through the lens of Mark Twain, and I want to explore another perspective. Mark Twain is like Mount Rainier in Washington state, so dominating the terrain that is it difficult to escape his shadow.

My research in this project centers on the 1850s, and I am happy to say that there is more satire there than is usually discussed, a perfect example of what might still remain to explore in earlier historical contexts. The star of that book will be Sara Willis Parton and her persona Fanny Fern.

Want to hear more? Jim spoke on this panel for the New Book Talks with the AHSA that focused on New Books on Satire.