Want to order the book? Here is a discount code: ZOOM40

T ell me about your start in humor studies. How and when did you begin pursuing it as a subject? who or what has influenced you as a scholar of humor?

In some ways, my "study" of humor began at a very early age. I like comics as a kid. I also really liked television cartoons- The Simpsons, of course, but also shows like Pinky and the Brain and The Ren & Stimpy Show when I was fairly young, and then South Park and Family Guy when I was in high school. And I was a huge fan of The Far Sidecomic strip and the magazines MAD and Cracked. You can most certainly see these influences on some of the things I have written about as an academic- MAD, for one example unrelated to my book, as well as the obvious: editorial cartoons. But these influences were there, too, in my interests as an undergrad and in my decision to more formally start studying the role of humor in public culture, for instance in the comic antics of Kurt Cobain. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Cobain for a course in rhetorical criticism, and focused my attention on how he used humor in interviews and public appearances and concerts to disrupt his celebrity and throw wrenches in the spokes of the corporate system of music production and hero-never mind anti- hero-worship.

I also wrote about the humor behind Hunter S. Thompson's so-called Gonzo journalism, in addition to the comic artworks of Thompson's longtime collaborator, the British caricature artist and illustrator, Ralph Steadman. I should also note that I've always dabbled in pen-and-ink drawings myself. In grade school and then again in middle school, I was known as the kid who could draw. That reputation has stuck to this day, with both friends and family members asking me whether or not I drew the picture of Uncle Sam by Francis Gilbert Atwood for my book when they first saw the cover. All of this is to say that a deep immersion in various things that can be seen as comically artful and, by extension, humorous paved the way for the intellectual pursuits that have motivated me since I was a burgeoning academic.

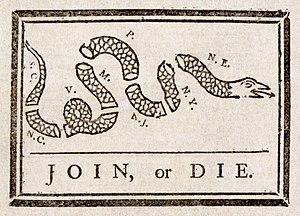

The initial impetus for this project grew out of my fascination with the extent to which editorial cartoons have long served so many rhetorical purposes in U.S. American wartimes. Since the Founding Period, they have been used for propaganda, military recruitment, criticism, and so on. What I realized more and more, though, as I looked into editorial cartoons in specific moments of both armed conflict and political crisis (which, in our history, often go together) is that they are frequently at the center of images and ideas about cultural identity. Consider Ben Franklin's early artwork that dabbled in depictions of something like national union in his appeal to join or die.

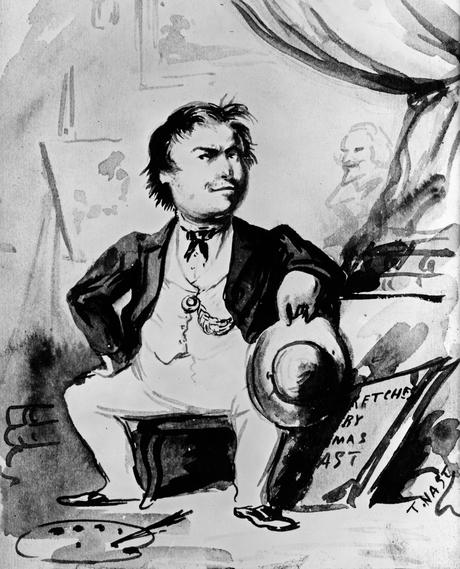

Consider Thomas Nast, an Irish immigrant, in the Civil War era making caricatures of Americanism with a nationalistic kind of liberalism that pushed him toward the heart of principles that we all like to say are part and parcel of who we are. Liberty. Freedom. Opportunity. And consider that Nast's work over and again appealed to the better angels of civic virtue as they come up against the vices, and even the violent spasms and paroxysms, that emanate from our political differences, i.e., xenophobia, racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice that undermine-or, sadly, under write -collective pride.

Then there's the collection of editorial cartoons about American Empire at the turn of the twentieth century and their mockeries of our emerging war machine as an arsenal of democracy unto itself that swelled during the two world wars. I could go on with references to the Cold War and the post-9/11 milieu and the rhetorical mire of our present moment, making connections between notions that the might of militarism blends with the righteousness of presumed manifest destiny. Suffice it to say, though, that in this entire complex history is a certain comic spirit that imbues caricatures of American cultural identity, and thereby national character, from war posters through reflections on cultural warfare in comic illustrations to revilements of warism and its collateral damages in editorial cartoons. Quite simply, I wanted to know why, in addition to how this trajectory of wartime caricature lends a powerful and dynamic endurance to comicality in our national character.

.

Your book-Caricature and National Character-focuses on how political cartoons during times of war help us understand American character. Can you give us an example that demonstrates your approach?It is so hard not to point you to the cover of my book since the image there encapsulates what might be seen less as either a democratic or an imperialistic leap of faith, propelled by a war mentality, than a leap of foolishness. That's what caricature captures, in a rhetorical sense: combinations of wisdom and folly, sense and nonsense. That Uncle Sam is blindfolded further betrays a sort of metaphor for caricature as a means of making comic imagery into a looking glass for our ways of seeing-and our ways of not seeing.

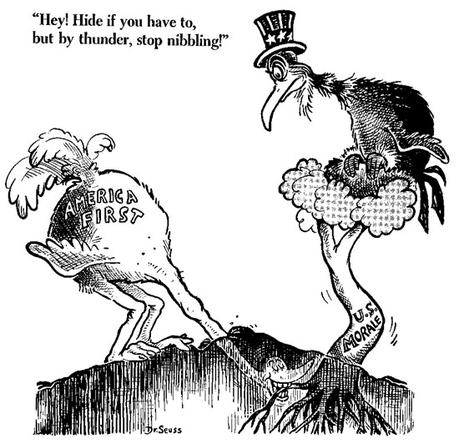

To say that the U.S. or any other nation has something like a "national character" is to suggest that we need to see ourselves in particular ways through the lenses of our historical principles and peculiar institutions. It is to imagine ways of being as they are impelled by ways of seeing various points of shared identification that exist, however blatantly or flagrantly or latently, in our collective consciousness. Such a comic imagination carries through every chapter of Caricature and National Character. We see it in the view of citizens at arms in Flagg's "I Want YOU!" poster. We see it in Dr. Seuss's image of an ostrich with its head in the sand. We see it in Ollie Harrington's goad for us to look at who we are through the eyes of children. We see it in Telnaes' entire framework for reimagining the prideful arrogance of a democratic nation that-much like the Uncle Sam that fills out the cover of my book-is on its way toward the Fall, precipitating the death of democracy on the precipice of a people's own making.

I guess what I am getting at here is that my combination of cultural critique and rhetorical analysis relies on an assemblage of caricatures that grapple with ways of seeing how national character gets represented and recast for the sake of comic judgment. Variations on persistent themes matter a great deal here, which is why no single image will do.

.

What influence do you hope your book might have on conversations in humor studies? In other fields?One hope is simply that readers either revisit or rethink editorial cartoons! They are still very much alive and, well, animated in our public culture.

I also hope that Caricature and National Character provokes renewed conversations about editorial cartoons, and caricature more broadly, in terms of public communication that is usually considered to be so utterly time-bound and so utterly topical that it is misrepresented as something to be seen once and then set aside. It is a fairly conventional perception that editorial cartoons provide a quick jolt or a laugh, but then give way to other modes of understanding around what is going on in the world. They are usually only conferred special purchase when they are controversial. A central element of my argument in this book as that caricatures in editorial cartoons and other comic illustrations are extraordinary precisely because of how ordinary they are in the conveyance of what matters to bodies politics both at specific moments in history and across the annals.

Then there is the aspect of caricature that goes beyond any discernible sense of humor. Perhaps scholars and other readers will look at the rhetorical force of caricature not just vis-à-vis human folly in the comic sense but also in terms of the hardline, hard-nosed, hard-hearted, and even fanatical ideologies that more than ever seem to lead so many of us to look at other people as little more than strangers and enemies in our midst. Along these lines, I would be delighted to discover that Caricature and National Character urges us to recognize that humor can certainly be used to preach to the choir, that it can constructively be used to sustain what Jim Caron dubs a "comic public sphere," but that it can also be used, if not mis used, to promote festive styles of hatred and crude carnivals of-to borrow a phrase from Hunter S. Thompson-fear and loathing. This latter dimension of humor requires our attention.

Finally, it is my sincere hope that scholars in other fields and readers beyond those interested in humor per se might turn to some of the arguments I make in this book to work out the variety of ways in which warism is baked into our official politics, our media cultures, our images and ideas about how to (in a weirdly Wilsonian way) keep the world safe for democracy. On the scholarly front, I wonder what people will think about where to go with comic imaginations if we are to turn toward rhetorical means of protecting and defending democratic institutions without recourse to the wiles of political officials or the soft powers of strong states. In more lay terms, I wonder what we might do to take pause with caricatures that situate our perspectives and opinions and beliefs on the comic edge of a distorted mirror that doubles as the oddly, distortedly, yet no less picture-perfect portrayal.

.

What trends do you see (or wish you saw) in humor studies? What do you hope for the future of the field?

There is such a rich tradition in humor studies of scholars really showcasing that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like, and doing so in a way that more often than not demonstrates the unique value that these modalities bestow upon humanity. I say this because I came to humor studies with an honest sense that others in the intellectual community shared my sense of just how vital what we study is to any understanding of everything from the progenation of rhetoric (let alone philosophy) through the establishment of so many societal divisions between upper and lower, sacred and profane, civil and brutish, etc. to the everyday dealings of human beings as homo ridens. I say this, too, because my hope for the future of humor studies is that it will continue on its trajectory of garnering more and more attention, more and more scholarly respect, and more and more acclaim as a site for dynamic academic inquiry.

Still, I do think there is even greater room for humor at the heart of cultural studies and rhetorical analysis. These days, perhaps more than ever, that which is humorous, comical, comedic, and the like is problematic-and I mean this in the Foucaultian or Deleuzean sense that something needs to be problematized-in that these things need to be subjected to new questions about why they are important, why they are relevant, and even why they are at issue with conventional ideas regarding what makes, say, this or that iteration of humor humorous, or even what makes humor humor, and then again how we understand it as "good" or "bad" or somewhere in between. Some of the best scholarship on humor is not caught up in definitional or conceptual hairsplitting-at least not solely. Rather, it is tied to matters of politics, identity, communication, justice, judgment, and more. People are looking differently, for instance, at the comic spirits in activism and outreach that persist to deal with some of the darkest aspects of the human condition, i.e., racial bigotry. I and others are re-imagining the relationship between pleasure and pain as it is manifest in things like satiric films and stand-up comedy acts. I and others are also rethinking comedies of human survival in the face of literal catastrophe. This includes earthly devastations with regard to climates and species. It includes cultural crises such as racism, gun violence, and political divisions that traverse the boundaries of life on the streets, so to speak, and the policy measures that stem from seats of government. I can only imagine that humor studies will see redoubled efforts by scholars to connect their subjects and objects of interest to these all too real circumstances of life and death.

.

What's next for you?It feels a little strange to start talking about a second book just months after my first book was published, especially because I want to honor the work I did and the energy I expended to put the ideas of Caricature and National Character out into the world. But I have a hard time sitting still, and so am already in the initial stages of developing a new manuscript. It is very much in keeping with what I just mentioned about problematizing studies of humor, and it will be about what I am characterizing as instances when comedy goes wrong. The project will have a historical angle. However, it will be more focused on recent times than Caricature and National Character, which has its origin stories in the years leading up to and then carrying on from the First World War. Beyond the second book, I have a number of side projects in progress as well as a feeling that some rest and relaxation might serve me well in the waning days of summer! Nevertheless, as I often suggest when I sign off: more soon.