Trumpeter Swans (Cygnus buccinator) at one time were familiar sights in southern Ontario during periods of migration, but due to over hunting in the 18th and 19th centuries, for their feathers and their skins, as of 1886, they had vanished from the region. That year, a hunter at Long Point on Lake Erie shot the last known trumpeter swan that was migrating from the west.

A vigorous restoration program that began in the early 1980′s has seen a significant comeback of the trumpeter swan population in south-central Ontario. Earlier this March, on the shores of Lake Couchiching, Bob and I caught up with two members of the trumpeter swan family as they began their migration back to their breeding grounds.

Because most of the trumpeter swans seen in Ontario have been raised in breeding programs, they are different from wild swans and don’t know how to fully migrate. They come south in November, from places like Wye Marsh, Kirkland Lake or North Bay, and then return there to spend the summers. Part of the breeding program requires the swans to be banded and tagged in order to keep track of their progress.

Trumpeter Swans weigh more than any other bird native to North America with adults weighing between 15-30 pounds, and they have a massive all-black bill.

They are also pristine white, long-necked birds with no black in the wing tips.

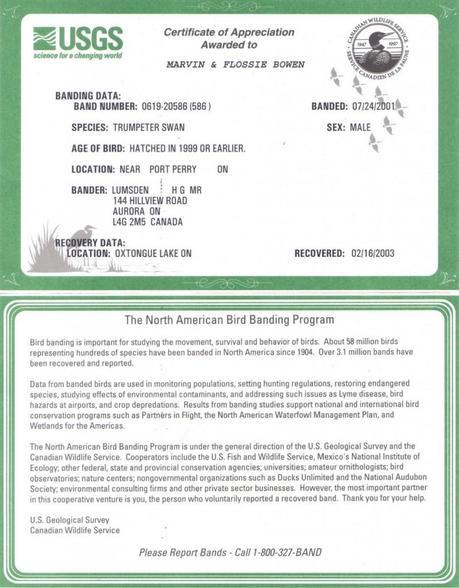

With the aid of registered tag numbers and bands, it is possible to identify individual birds, monitor their nesting and migrating patterns, keep track of their mates, and make note of their longevity. These birds are long lived and form long-term bonds with their mates.

The person credited with helping to reintroduce the Trumpeter Swan back into Ontario is Harry Lumsden. In 2008, the Ontario Field Ornithologists honored him with the presentation of their Distinguished Ornithologist Award, seen above. In 2009, he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Ontario Heritage Trust for those same efforts.

As luck has it, back in 2003, my parents spotted a Trumpeter Swan on Oxtongue Lake, in Ontario. They were able to record the band number and judiciously reported it to representatives of the North American Bird Banding Program. As we can see from the certificate sent to them, it is the same Harry Lumsden who banded that swan as started up the restoration program of trumpeter swans in 1982. He was involved with that effort for over 30 years.

Last November, Bob and I hiked the Cedar Trail in Rouge National Park, and on one of the many ponds located there, two Trumpeter Swans were lazily spending some downtime.

There are well over 1,000 Trumpeter Swans in South-Central Ontario now, and about 200 of these winter in Burlington. Some have learned how to cross Lake Ontario and winter in those warmer climes wherever they find abundant food. By tracking their tags, it is known that almost half of the birds that head to The States are never seen nor heard of again. They are assumed dead.

The soft, pliable webbed feet of the Trumpeter Swans are partly responsible for their decimation. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, hunters would harvest the feet, which were then made into change purses. The skins of the birds were used to make powder puffs, the largest flight feathers made what were considered to be the best quality quill pens, and the pure white feathers were prized as adornments for fashionable hats.

Trumpeter Swans emit a loud, trumpet-like, slightly guttural ko-hoh sound resembling the bleats of a bugle.

In this video that Bob recorded, you get to see the Trumpeter Swans at Washago.

Mute swans, on the other hand, are so named because they make no vocalizations at all. They can be distinguished from Trumpeter Swans by their orange bills.

Mute swans are an invasive species introduced from Europe because of their graceful beauty. One impediment to the growth of the Trumpeter Swan population around the Great Lakes area is the presence of the growing non-migratory Mute Swan population that competes for habitat.

Bob and I observed these Mute Swans in January, swimming on Lake Ontario, just off the shore from the Cranberry Marsh in Whitby. Ironically, back in the 1980′s, it was here at the Cranberry Marsh that Harry Lumsden, along with his birder volunteers, placed the first Trumpeter Swan eggs to incubate under feral Mute Swans. But on the day we visited the Lynde Shores Conservation Area over 30 years later, all we saw were Mute Swans.

For now, let’s hope for the continued success of the restoration program to preserve the existence of the native Trumpeter Swan. Thankfully, the present population of these indigenous waterfowl is self-sustaining.

Bob and I have reported through ebird Canada the tag numbers of those Trumpeter Swans we have observed. ebird Canada uses information submitted by even casual bird watchers to keep track of and study bird behavior and populations from one year to the next.

Although Bob and I saw only two Trumpeter Swans at the beach in Washago, a resident of the area informed us that, actually, between 49 and 80 of these waterfowl have been sighted in the area over the course of the winter.

Checkout some of our other bird sightings:

Bufflehead Ducks sighted at Rouge National Park

Ruffed Grouse sighting in Algonquin Provincial Park

Frame To Frame – Bob & Jean

Trumpeter Swans on the Shores of Lake Couchiching is a post from: Frame To Frame