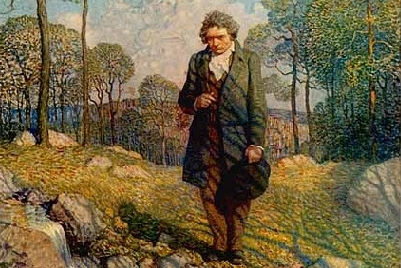

Beethoven and Nature.

Detail from the painting by N.C. Wyeth.

What is program music? This is a question that musicians and music critics have been wrestling with (and generally losing the match) for 200 years. The debate started in 1808, the year that Ludwig van Beethoven premiered his Symphony No. 6 in F Major, the Pastorale. While it would be Hector Berlioz who created the first detailed program for a symphony 22 years later in his Symphonie-fantastique, Beethoven pointed the way forward by substituting movement titles for the usual tempo markings.

It's hard to believe that this work premiered on the same long bill of works as the Symphony No 5 in C minor, the heaven-storming experiment constructed entirely from a four-note motif. That symphony had told a story too, transmuting dark C minor into glowing C Major, taking the stony path to triumph over inexorable Fate. It was unconventional in its playing if the last movements together, of reprising the plucked andante in the middle of another movement, and in its emphasis of rhythm over medley.

The Pastorale was a rule-breaker too. To start with, it was in five movements, not four. And instead of following the traditional form, Beethoven used the format to tell a story, of an idealized day out in the Austrian countryside. The first movement "genial feelings Jon arrival in the countryside" is built around a simple lilting theme that repeats and expands, blossoming in the orchestra. One can hear the freak of a carriage, the crunch of a gravel road underfoot, and the dapple of sunlight through leaf and branch.

The recording used as the basis of this article is the 1981 Berlin Philharmonic version with Herbert von Karajan, from the fourth (and last) of the Austrian conductor’s Beethoven cycles. Karajan takes the second movement surprisingly fast, hurrying the ripples of the brook along but slowing down enough for the detailed bird calls to emerge in the woodwinds. The Berlin players achieve a meditative balance here, the beauty of a summer’s day expressed by Beethoven at his most poetic.

Austrian ländler rhythms dominate the third movement, a rambunctious whirl of celebrating, clod-hopping peasants. This simple country dance is bucolic, interrupted by the violas and cellos sawing minor chords like an overenthusiastic town band. The achievement here is that Karajan makes the music sound at once rustic and refined: precisely and energetically played but still keeping its country soul.

Then all hell breaks loose. The twittering birds and dancing peasants are swept away by the raw fury of primal Nature. Haydn was Beethoven’s model here, as the flutes and oboes conjure howling winds and the timpani supplies the boom-crash of thunder and lightning strikes. It is not unfair to say that this is the most epic orchestral donnerwetter (thunderstorm) written before Verdi’s Rigoletto in 1851.

And then the tempest stops. The sun comes out. And without pause, the clarinets and horns sound a call over the mountainside. The strings begin a new theme: a gentle, loping figure based on an Austrian mountain shepherd’s song. This melody is repeated, varied and expanded upon to become a grand and glowing orchestral sunset, bathing the aural landscape in color and light. Following one last recapitulation for a solo cellos (hearkening back to an idea also used in the Fifth) the work ends with the certitude of an "amen" in its last two chords.