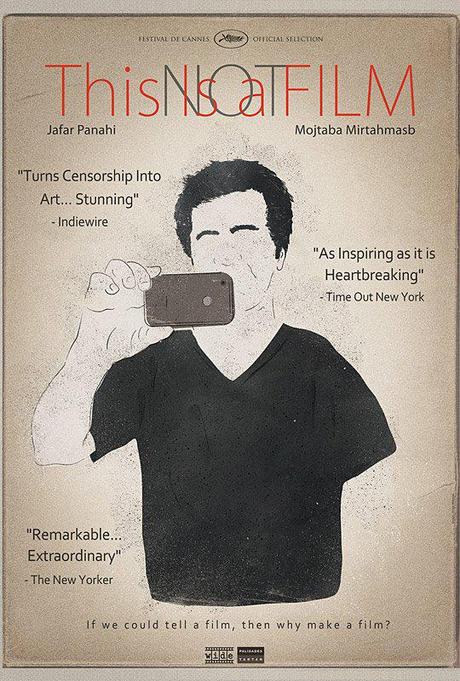

This Is Not a Film (2011)

Director: Jafar Panahi, Mojtaba Mirtahmasb

Cast: Jafar Panahi

Runtime: 75 minutes

FilmScore: 10/10

In Short: Mesmerizing; a beautifully simple but incredible effort

“You cannot say ‘cut.’” There is a moment in what may be Jafar Panahi’s last project in a long while where the popular Iranian director wants his friend and associate Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, who is filming, to stop. Mirtahmasb informs him that because of the charges against Panahi, he is no longer a director, and has no right to say ‘cut.’ Panahi smiles weakly at this and chuckles, but behind the chuckle there is a brief moment of realization about the consequences of the heavy charges the Iranian government have laid against him, and the lifechanging punishment that is a result.

This Is Not a Film has an accurate enough title. Technically it is, but viewing it I would argue it isn’t. In the end credits, it is listed as an ‘effort,’ rather than a film, and I like this title. An ‘effort’ is much more precise and truthful than ‘film,’ and thus, I am judging it as such. I am not ranking This Is Not a Film among any other films, because to do so would be inaccurate. It is an effort, and a bloody good one at that. In this effort, Mirtahmasb films Panahi in the midst of his daily life, which after a crippling punishment from the Iranian government, is hauntingly empty. Panahi has been charged by the Iranian government with making propaganda films (though critics who have seen the films charged say they are anything but), and the misguided and frankly idiotic government have handed him a six-year prison sentence and a 20-year filmmaking ban. For a filmmaker, there is no injustice and suffering more devastating.

The events of the film are not plentiful. Mostly it consists of long sequences led powerfully by Panahi, off the cuff and inspired. Much of the film sees Panahi discussing his own films in a deep, thoughtful manner, discovering tiny details in some of them that make him proud to be a filmmaker. In one strong, excellent sequence, he reads from an unadapted screenplay he has written before his ban (which also forbids him from writing films) and enacts some scenes from it in his living room. He puts tape on the floor to map out an imaginary room, and shows how shots will start and end. His detail is meticulous, which makes the reality of this film’s unlikely creation even sadder. Mirtahmasb films this all with a mostly handheld camera.

Then, in the effort’s strangely different but suitable final third, something wonderful happens: Panahi holds the camera and films the entire final sequence. This may perhaps be the last time he holds a camera in a long while, and though what he films – a conversation with an upbeat trash collector – isn’t particularly exciting, the knowledge that Panahi is doing this himself, off the cuff, and in such a powerful and rebellious manner, is simply inspiring and wonderful. He converses with the man who has come to pick up the trash, and their extended conversation is marvellous, and completely ad-libbed. What they talk about doesn’t really matter, but it is one tiny aspect of many that provide vital clues into the state of modern Iran and the way it has affected Panahi and his creative consciousness. Then the effort ends with an image that cannot have been planned or pre-organized, and works absolutely perfectly in summing up everything that has come before it and ending the effort on a haunting, mesmerizing note.

I would like to say that this is one of the best films I’ve ever seen, but of course, it is not a film. In its own lonely and unspecified genre, it is a creation of unspecific craftsmanship and ability. It was filmed on a practically nonexistant budget, largely unplanned, and absolutely perfect. Panahi’s words and actions are those of a desperate man whose creative freedom and ability have been robbed from him, but who still defiantly and compulsively urges to create. To see him articulate his thoughts on his films; projects completed or lost, ideas formed or fragmented, is simply fascinating and ultimately saddening. Panahi does not instruct us to get angry at the Iranian government; he knows we will feel the way we feel, and politics don’t matter at all. This is simply him, not a filmmaker but a man, given what might well be the final opportunity in a long while he will ever get to lay his hands on one of mankind’s finest creations.