A little over halfway through Wake in Fright, what had been an uncommonly tense version of something I'd broadly describe as After Hours: Outback Edition suddenly turns into a kangaroo snuff film. It's one of the most disturbing movie scenes I've ever seen.

This requires more explanation.

Australia Stands Condemned

Adapted from a Kenneth Cook novel, Wake in Fright is a 1971 thriller about a civilized school teacher who wants nothing more than to be unshackled from his government-mandated small town teaching position. Naturally, he views himself as superior to all of the Outback yokels who populate the area, but when he ends up stranded in a dying mining town he goes native and gains a better understanding of just how quickly isolation and desperation can lead to what we would now call "toxic masculinity."

Upon the film's release, it was regarded as a stark referendum on the Australian character. The Sydney tabloid The Daily Mirror wrote, "[It] will shock and disgust and trigger off tidal waves of indignation from those who still believe our outback is the backbone of the nation." In the Melbourne Age, Colin Bennett's review was even more succinct: "One way or another [we] stand condemned."

When Wake in Fright finally made its way out of Australia, Pauline Kael had this to say in her New York Times review, "The rough white men out there in the wilderness are a new race to us. They're beasts but not villains; they're 'decent' and unaware of wrongdoing and that suggests that they are unreachable...You come away with a sense of epic horror."

The Lost Classic

Despite all of the accolades, Wake in Fright flopped and was quickly lost to time, existing only as an edited print which was so low quality it was never transferred to home video. Somewhat miraculously, the negatives were discovered in 2002 in a Pittsburgh shipping container labeled "For Destruction." By 2009, a fully restored, uncut version of the film was screened at Cannes, making Wake in Fright one of the only movies to have premiered at Cannes twice - first in '71 and then again 38 years later.

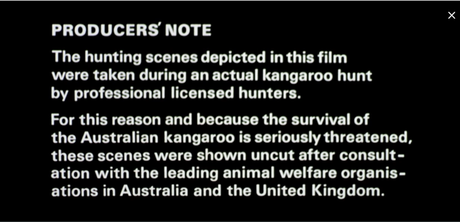

At the '09 screening, 12 people walked out during the sequence where live kangaroos are killed on screen, like an Aussie version of Cannibal Holocaust's infamous sea turtle dismemberment scene. When Shudder recently added Wake in Fright to its "Borderlands Horror" collection, whoever is responsible for the little blurbs about each movie made sure to include the following disclaimer:

I didn't read or know any of that beforehand. Instead, I picked Wake in Fright based solely on its title and cover as well as my post-Next of Kin interest in Australian exploitation cinema. Wake in Fright, however, is a bit of a different beast.

Horrific, But Not Really a Horror Movie

John Grant (Gary Bond) - a school teacher who looks like an Aussie Robert Redford mixed with Peter O'Toole circa Lawrence of Arabia - doesn't encounter zombies, the apocalypse, a gang of curiously attired road warriors, threatening wildlife, crazy-eyed locals with a big secret, or any other Australian horror movie trope you might expect.

Instead, what happens to him in Wake in Fright is quite simple: he ends up stuck and penniless in a small town, bums free beer and somewhere to sleep off the locals, and rather quickly blends in as just one of the guys, turning to drink, boisterousness and sport to conceal quiet desperation. What else, apparently, is there to do in such a forgotten corner of the world than to drink, fuck and kill and then drink some more?

It it is hardly a flattering depiction of the Outback and the people who live there. An actual horror movie would make that point through metaphor or genre conventions; Wake in Fright does so more directly and is the more unsettling viewing experience as a result. Martin Scorsese, who knows a thing or two about disturbing movies, has been a huge Wake in Fright champion since catching its Cannes premiere in '71. He was instrumental in getting the restored cut back into Cannes, arguing at the time:

Wake in Fright is a deeply - and I mean deeply - unsettling and disturbing movie. I saw it when it premiered at Cannes in 1971, and it left me speechless. Visually, dramatically, atmospherically and psychologically, it's beautifully calibrated and it gets under your skin one encounter at a time, right along with the protagonist played by Gary Bond. I'm excited that Wake in Fright has been preserved and restored and that it is finally getting the exposure it deserves.

It Starts Out So Innocently

The movie sneaks up on you. It starts out amiably enough, following a disgruntled school teacher practically leaping out the door once the Christmas holidays start. He has saved up enough money to buy a plane ticket to visit his girlfriend in Sydney, but to make the flight he first has to take the train to a nearby mining town called Bundanyabba. As he kills time at a local pub and is quickly escorted around by a friendly policeman, you quickly pick up that he thinks himself better than the unwashed masses of the town, no matter how outwardly friendly they all seem to be.

The local doctor, played to off-kilter perfection by Donald Pleasance, points out Grant's snobbishness, but he does so with a laugh and curious smirk, which seems to be enough to get the good school teacher to lighten up. Soon enough, Grant joins in an illegal, backroom game of two-up, a completely bonkers but very real game in which someone tosses two pennies in the air and onlookers place bets over heads, tails, or split between heads and tails. I can't decide what's more surprising - that two-up actually exists or that director Ted Kotcheff took a game of heads or tails and turned it into one of the tensest gambling scenes any filmmaker could ever hope to capture.

Grant enjoys a run of good luck, but then gets greedy, thinking he might be able to win big one more time and walk away with enough money to finally buy his way out of having to teach at a small town. Instead, he loses everything, setting him up for a series of increasingly bizarre encounters with the locals who are sympathetic to his plight and/or think he might make for a good drinking buddy. There's always someone new willing to hear his tale of woe out over a pint or two.

The Kangaroo Hunt

Somewhere buried in there is one extra long night which begins with Grant and the lads drinking at a pub and ends with them destroying it in a drunken rage. In-between that, they head out into the Outback to hunt kangaroo, mostly for shits and giggles as well as a way for the rough and tumble lot to initiate the school teacher. Grant winces at times, as if remembering that the old version of him wouldn't enjoy this, but then he jumps out of the truck to deliver the final blow to a wounded baby kangaroo.

I didn't know any of this was coming, and even when it did arrive I tried every mental trick I could think of to convince myself that I wasn't actually watching real kangaroos being shot, stabbed, and generally slaughtered by a group of laughing, drunk idiots. Surely director Ted Kotcheff, the same man who later directed First Blood and Weekend at Bernies, was using a combination of clever camera tricks and convincing dummies to simply give the illusion of murder.

As the violence escalates and a montage of kangaroo kill shots flashes by, contrasted with the faces of the drunken hunters laughing and pouring beer over each other, it becomes harder to think it's just movie magic. No, they really killed those kangaroos, a fact the film itself acknowledges with the following disclaimer attached to the closing credits:

How They Did It

In Peter Galvin's three-part feature on the history of the film, he offered far more context:

THE KANGAROO HUNT in Ken Cook's book is a callous slaughter, an orgy of destruction, played out in a party-mood. In an early version of the script version, screenwriter Evan Jones had changed the novel's kangaroo massacre into a pig hunt. "It was only after Ted Kotcheff had been on his first survey for locations in and around Broken Hill (in December, 1969) that the kangaroo hunt had been re-instated," explains Tony Buckley in his book, Behind a Velvet Light Trap.

But that decision caused Kotcheff and the crew a lot of agony. At the time there were approximately 30 million kangaroos in Australia, a portion of which were regularly slaughtered for sport, and food products every day, by hunters who were not operating under any regulatory authority, and the rest by farmers protecting their interests and still others, just blokes really, letting loose on the animals in a 'larrikin' spirit.

The attitude between city dwellers and country folk was very different when it came to the destruction of animals, especially those in the wild. In the bush, 'Roos were considered a menace. They wrecked fences and ate into the food supply intended for cattle and sheep. But for a lot of Australians, the kangaroo was a national symbol; a harmless and defenceless species to be protected and preserved. There was a powerful and very real sentimental attachment to the kangaroo.

It was thus not a universally popular decision to keep that portion of the book in the movie, but the production moved forward with it anyway, hiring professionally licensed hunters, gifting them a giant lighting rig designed to light up the night as well as the frame for the camera, and then they filmed the resulting carnage. Like the characters in the movie, however, the hunters eventually got far too drunk.

"By 2AM the hunters were getting really drunk and they started to miss," says cinematographer Brian West. Wounded kangaroos were hopping about helplessly, trailing their intestines. "It was becoming this orgy of killing and we (the crew) were getting sick of it." West had a private word with the gaffer Tony Tegg, who arranged a 'power failure'. "I told Ted that we didn't have enough light to continue." The crew headed back to Broken Hill, some of them fighting back tears.

The sequences with the actual actors didn't result in any kangaroo deaths. The worst thing they did was hold a kangaroo's tail to hold it in place as they filmed the scenes where the guys actually get out of the truck and box a couple of the buggers. Still, by the time they edited all the footage together and ran it in a movie theater for an editor's screening, the pale-faced projectionist hopefully asked, "You're not going to show that, are you?" Later, one of the producers reportedly fainted when he saw the footage.

How They Reacted

It was Ted Kotcheff's decision to film the kangaroo hunt, and he's the one who kept the footage in the movie. When it premiered at Cannes, a very young Scorsese, who only had Who's That Knocking At My Door and Street Scenes to his name at that point, actually sat behind Kotcheff and offered a practically involuntary commentary throughout. As Kotcheff remembers it, "[Scorsese] was enjoying the film, but he was very shocked, He was going, 'oh, oh, oh no'...and 'they're not, they're not...they're, they're going to go all the way!'"

That's roughly how I reacted to Wake in Fright as well, unnerved but also intrigued to see where John Grant's journey would take him next. The kangaroo hunt disturbed me so much because it's something I've never seen before. I didn't even know people hunted them.

As the film makes a point of emphasizing, the roos are kind of already anthropomorphized, which makes hunting them for no reason all the jarring as a visual image. When you juxtapose that with the moral descent and ugly self-discovery of a protagonist who starts out so civilized and then throw in the empty-headed laughter of the hunters and you certainly get a sense you are watching a statement movie. Here's Ted Kotcheff showing us real Australians shooting the country's unofficial mascot, laying bare a perception vs. reality divide. Did he have to do it by killing real animals, though?

When they remade this as a 2017 mini-series, they didn't kill any kangaroos. Ironically, they took screenwriter Evan Jones' original idea from decades ago and changed it into a hunt for feral pigs.

Wake in Fright is currently available to stream on Shudder.

Grew up obsessing over movies and TV shows. Worked in a video store. Minored in film at college because my college didn't offer a film major. Worked in academia for a while. Have been freelance writing and running this blog since 2013. View all posts by Kelly Konda