I dare to venture a guess that most history scholars have at one time or another used a political cartoon to make a historical point, be it in class, in a publication, or even privately in discussions with laymen. In fact, walking through a history department you are bound to find a political cartoon adorning a wall or a professor’s door. Political cartoons are indeed excellent historical source material. The problem is that most of the above uses are superficial and seldom live up to the standards of source criticism historians work by. Reading a cartoon, especially a historical one, is not a “natural” process; it takes work and an understanding of not only the period in question but of visual analysis, of the artist, and of the publication.

With proper methodology cartoons can be even more valuable material for historians than their neighbors on the op-ed pages of daily papers. This stems from the cartoons wide circulation among the readers (studies have found political cartoons to be among the most read parts of the paper), from their encapsulation of salient issues of the day, but perhaps most of all from the fact that a successful cartoon captures the contemporary mentality by essentially using already accepted, or at least, widespread ideas. A few more words on this last aspect; many scholars argue that cartoons have to communicate known ideas for them to be understood and appreciated. Cartoonists tend to agree; “the idea contained in a political cartoon must not only be easily understood but even be already widely established before the cartoonist uses it”, British cartoonist Nicholas Garland explains. Essentially the cartoonist encapsulates the public awareness of an issue and then adds a recognized commentary. This is one of the reasons Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed cartoons to be “often the truest history of the times”. As communication scholar Janis L. Edwards concludes; “political cartoons historicize the present and form a collective record of the social imagination regarding events in political life”.

Considering the frequent use of individual cartoons and the potential of cartoons as source material it is striking how limited historical research of political cartoons is. In fact, Kent Worcester goes as far as comparing the existing scholarship on cartoons to that on political campaign buttons. The most frequently cited reason for this lack of scholarship is methodology. In increasingly inter-disciplinary academia this is, however, no longer an acceptable position; historians must be able to utilize the theories and methods of art history as well as of humor studies and communication studies. A more pressing concern is the limitations the existing lack of scholarship on cartoonists constitutes for any research on their work.

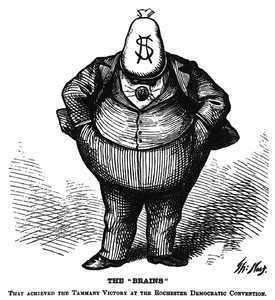

Thomas Nast’s famous depiction of Boss Tweed (Harper’s Weekly, October 21, 1871)

Thomas Nast, the cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly who “took down Boss Tweed”, is generally accepted as the Great American Cartoonist, and indeed of him there are a few historical biographies ( I review Fiona Deans Halloran’s recent Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons in the upcoming issue of Studies of American Humor). Beyond Nast, the proverbial Hall of Fame for cartoonists is populated by talents such as Joseph Keppler, Homer Davenport, Rollin Kirby, Edmund Duffy, and Ding Darling. Of these earlier cartoonists and influential members of the American press there is some, if limited, historical research; Richard Samuel West’s work on Keppler and Darling, Leland Huot’s book on Davenport, and S.L. Harrison’s research on Edmund Duffy stand out among the few.

Relevant historical work on modern cartoonists is even scarcer. Most scholarship on modern, post-WWII, political cartoons cite four or five cartoonist as the crème de la crème of the field; Bill Mauldin, Herblock, Paul Conrad, Timothy Oliphant, and sometimes Jeff MacNally. Limited, if any, significant historical work on these cartoonists has been done. The lack of scholarship is hardly outweighed by the numerous autobiographical books the authors have penned; most of these (for example Conrad’s I, Con: The Autobiography of Paul Conrad, Editorial Cartoonist) are collections of cartoons with appreciated but limited biographical tidbits in between. The praised volume on Herblock by Harry L. Katz and Haynes Johnson, Herblock: The Life and Works of the Great Political Cartoonist, suffers from the same problem; they let the picture speak for themselves, which is of no help to those who know the pictures and are seeking the background.

One of Paul Conrad’s later pro-choice cartoons (Los Angeles Times, November 21, 1988)

If historians are to use political cartoons as source material, and they clearly should, we must start by increasingly looking at individual cartoonists. Mauldin’s cartoons cannot be understood without understanding his war experience and especially his experiences upon coming home from the war; Conrad’s cannot be understood without understanding his Catholic faith and his personal evolution on the issue of abortion; Herblock’s cannot be understood without understanding his identity as a Washingtonian, etc. Let this be something akin to a thrown gauntlet; historians must start paying serious attention to the journalists/artists behind the political cartoons.

(c) 2014, Oscar Winberg

Oscar Winberg has a M.A. in history from Åbo Akademi University where he is currently a doctoral student, also in history. His main field of research is the rise of conservatism in the United States. His current research is on the discourse on welfare and taxes in American television sitcoms from 1970 onward. This means that he gets to work with material that has been with him since the 1990s, when old reruns of shows like All in the Family and The Cosby Show was a staple of the after-school offerings on Finnish television. His master’s thesis was about ideological conflict within the Republican Party using editorial cartoons as source material. He has presented on ethnic identity and integration on the sitcomModern Family. He also contributes blog posts for the John Morton Center for North American Studies. If you feel inclined, check out his tweeting, @WinbergOscar.