BC&H will be on international hiatus from March 21-April 6, but I’ll look forward to catching up with everyone’s running exploits when I return. In the meantime I wanted to re-blog the following… thanks to Jim Benton for creating and Bora Zivkovic at Scientific American for sharing it. If there exists a legitimate use for the letters “LOL,” it’s here:

And with that, the blog must go on… don’t forget to leave interesting and thought-provoking comments below!

*******

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.

- Robert Frost

Strategically, this 30-mile route traverses much of the greenery and scenery in the East Bay

If you read this blog with any regularity, then my preference for trails over asphalt is no dirty little secret (dirty yes, secret no). I’ve even taken to running much of my speedwork on our local dirt track. But even in the Bay Area, with its (appropriately) liberal trail system, roads are an unavoidable fact of life for most runners. And although we prefer to shape it into eye-catching forms such as “international orange” bridges and the nicest baseball park in the country, concrete still dominates our urban landscape.

So it’s inevitable that most of my training mileage is logged on concrete. This is particularly true during the winter (i.e. rainy) months, when trails become saturated and I’ll do anything to avoid running indoors on It-Which-Must-Not-Be-Named. And sometimes embracing my inner asphalt junkie becomes equal parts necessary evil and training strategery, as when I’m prepping for a road marathon. Nothing simulates the physical monotony of concrete quite like the physical monotony of concrete.

Fortunately in the Bay Area, running on concrete doesn’t have to mean flat and boring. This is most important for the long slow distance (LSD) run that forms the backbone of the conventional marathon training regimen. Through hours of repetitive foot-striking on unyielding paved surfaces, the LSD training run builds physical and mental endurance by strengthening tendons, ligaments and the will to persevere despite frequent stretches of soul-squelching boredom.

For me the downside of the LSD isn’t the physical toll exacted by running 20+ miles at a time; instead, it’s the monotony of stringing together sidewalk mile after sidewalk mile through residential neighborhoods and strip malls, pausing occasionally to stiffen up at traffic lights while looking forward to the next curb as a much-needed source of elevation change.

With scenery like this, maybe they should rename it the Wrought Iron Horse Trail

Granted, flat and boring do make welcome bedfellows at times, as when I want to regulate my pace for longer distances, say 15-16 miles. In that case I retreat into an audiobook and hit the Iron Horse Regional Trail, a paved pedestrian and bike trail named (I presume) for how your joints feel after treading its 25 miles of concrete through nondescript East Bay suburbs – Now, Concord! now, Pleasant Hill! now, Walnut Creek and Alamo! On, Danville! on, San Ramon! on, Dublin and Pleasanton! But even the Iron Horse Trail has its own smattering of stoplights and trafficky intersections to hinder a runner’s progress.

Alternatively, if you’re looking to slowly liquify your hip flexors without the dangerous risk of encountering new scenery, you can always resort to hammering out endless laps around one of the local 400m tracks. And given the choice of the track or the treadmill, I figure a hip replacement or two later in life would be well worth the time spent outdoors now.

But on one recent weekend, feeling demotivated by the usual LSD suspects, I set out to take advantage of my surroundings and chart a LSD run that would be as un-flat and non-boring as possible. And by non-boring I mean scenic, not frogger-on-the-highway-dodging-cars exciting. My goal, which seemed improbable at the time, was to map out a scenic point-to-point course of 26 consecutive miles, entirely on paved surfaces, without a single stoplight. I ended up with nearly 30.

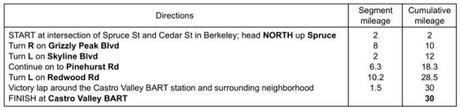

As I did in mapping a 32-mile course on trails across the East Bay, I’ve included a blow-by-blow description of my 30-mile route below. And in fact this route closely parallels that earlier 32-miler, the most notable difference being the terrain (asphalt instead of dirt). Despite its length, this route isn’t brain surgery; on the contrary, most 19th-century lobotomy patients – and even someone with my non-sense of direction – could find their way to the end without much difficulty. At the same time, rather than the typical flat and boring urban scenery, this course borders – and at times passes through – several of the East Bay’s excellent regional parks and preserves.

Sweeping views of the Golden Gate Bridge and Marin Headlands predominate up on Grizzly Peak

It’s hard to get anywhere in Berkeley without an uphill component, so it makes sense that a 30-mile run would be no exception. For some runners, the most daunting feature of the route won’t be its length, but rather its first six miles. Starting at the intersection of Spruce St and Cedar St in North Berkeley, the course immediately chugs up Spruce two miles and then along Grizzly Peak four miles for a net uphill gain of 1,300ft. Fortunately this first 20% of your day amounts to more “initial gut check” than “premonition of things to come,” as the course features a net elevation loss of 1,500ft over the next 24 miles. So overall this is a downhill course – and if that doesn’t scream “Boston qualifier” (in an Edvard Munch sort of way), then you’re not listening.

As uphills go, Spruce-to-Grizzly Peak amounts to moderate effort for maximal gain – the views across the bay are awesome. And as you continue your gradual but steady ascent along Grizzly Peak, adjacent to Tilden Regional Park, the panoramic vistas of San Francisco that greet you on a clear day also double as psychological (and unscented!) Bengay for your already-fatigued quads.

The course peaks at mile 6, at the southeastern edge of Tilden Regional near the entrance to the Steam Trains. At this point Grizzly Peak reverses trajectory, heading downhill with the occasional modest uphill jag over the next four miles. On the edge of the Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve, Grizzly Peak loses its bite and dead-ends into Skyline Blvd. Bank a left turn, and Skyline winds its way along a more-or-less level course for the next two miles. This is the ideal time to relax and settle into a rhythm as you navigate the Oakland Hills and soak in the views across the Bay. Fortunately the views up here are pretty much all you’ll be soaking in, because while the sun on most days will join you, its heat rarely poses a problem at any time of the year.

As Skyline Blvd enters Huckleberry Botanic Regional Preserve, it begins a definite downward trajectory and morphs into Pinehurst Rd, which will host the next leg of your journey into Redwood Regional Park. Six miles later, at the 18-mile mark, you’ll transition on to Redwood Rd as it exits Redwood Regional and enters Anthony Chabot Regional Park. For the next five miles you’ll border Chabot on your right and the branching Upper San Leandro Reservoir on your left, before the former seamlessly transitions into its sister park, Lake Chabot Regional.

I usually share this route through the Oakland Hills with a steady stream of cyclists, yet surprisingly few runners. Admittedly it does have its downsides for those accustomed to more urban running, but they’re relatively innocuous: 1) because sidewalks are scarce, I run primarily on the shoulder or side of the road; and 2) on occasion the winding course motivates me to zig and zag from one side of the road to the other, so I can stick to the outside lane and avoid startling an oncoming driver accelerating around a blind curve.

You may feel a bit uncomfortable initially if you’re new to these roads. But being able to lose yourself in your surroundings more than makes up for the occasional hassle of having to pay attention to them. Fortunately, the route is straightforward to negotiate and remains at two lanes for 26 miles, before widening and straightening out near its endpoint.

With that endpoint in sight, and as if to say “don’t let the door hit you on your way out,” Redwood Rd veers uphill one last time before putting Lake Chabot – and the relative solitude of the past 26 miles – in your rearview mirror and dropping you down into Castro Valley. Welcome to the suburban world of fenced-in schools, sprawling single-story strip malls, fast food joints and closely juxtaposed homes with HOA-approved lawns, all laid out block after block in characteristic grid fashion. Here at last you’ll encounter your first stoplight of the day, at Seven Hills Rd just past mile 27. So maybe it wasn’t quite 30 miles to your first stoplight, but then again after nearly 100,000 steps, 4,100ft of elevation gain, 4,300ft of elevation loss and 3,800 calories burned at an average pace of 9:46 per mile… after all that, really who’s counting?

One more mile down Redwood Rd, one wide anticlimactic loop around the Castro Valley BART station, and all good things must come to an end (unless you opt to turn around and ride that endorphin high all the way back to Berkeley). Nice job, foot soldier! If 30 miles of feet pounding concrete and concrete pounding feet doesn’t prepare you both mentally and physically for your next road marathon, well then that was a dumb way to spend five hours you’ll never get back, wasn’t it?

Happy as I’ll ever be to find myself in Castro Valley

If you had the foresight to bring a few dollars or a loaded BART card on your run, you can now happily collapse on the next available BART train to downtown Berkeley and disembark roughly ¾-mile from where your day began. Sit at your own risk though, lest your train arrive at and depart the downtown Berkeley station while you’re still valiantly struggling to pull yourself upright like a member of the zombie apocalypse.

In reality, despite their tranquil vibe and off-the-beaten-path allure, I’m guessing very few people cover these 30 miles all at once. After all, Highway 580 or even BART provides much more convenient and direct access to Castro Valley from most of the East Bay. And I’m guessing most folks who do travel this route do so as transiently as possible, from the relative comfort and disconnect of a fast-moving vehicle – all while focused on not bouncing a turkey, deer or cyclist off their hood.

But I prefer the (literally) more grounded approach… because it’s gratifying to think that even here and even now, there still are roads less traveled. Roads that, away from the watchful eyes of seven million Bay Area residents, don’t aspire to be ogled on TV, or friended on Facebook, or followed on Twitter. Roads that breathe at their own pace. Roads where silence is, if not golden, then at least not treated as fool’s gold. Roads on which you can either lose or find yourself, depending on which direction you’re headed. Roads that, in another time and another place, just might have been trails. I’ve invested countless man-hours seeking out and following these roads where they lead. On foot. As a runner.

And that’s made all the difference.

FINAL STATS:

Total distance: 30 miles (with no unplanned detours)

Total time: 4:53:18

Average pace: 9:46/mile

Elevation change (Garmin Connect Software): 4,076ft ascent, 4,278ft descent

Blow-by-blow directions for my 30-mile route from Berkeley to Castro Valley