Princess Louise, Graefle, 1864. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014

I often feel like Queen Victoria’s rather copious family is treated in much the same way as Henry VIII’s six wives – certainly I felt equal pride at being able to name them all in order at the age of seven, but also they have in many respects been reduced to a list of bland little cyphers that fails to encompass their true complexity: the clever one, the heir, the outspoken one, the pampered youngest, the artistic one and so on…

Although pretty, clever Vicky, Princess Royal, was my favorite of Victoria’s daughters throughout my childhood, I quickly switched my allegiance to her fascinating younger sister, Princess Louise Caroline Alberta, who was born on the 18th of March 1848, the sixth child and fourth daughter of Victoria and Albert and the first of the Queen’s labours to take place under the influence of ‘blessed’ chloroform.

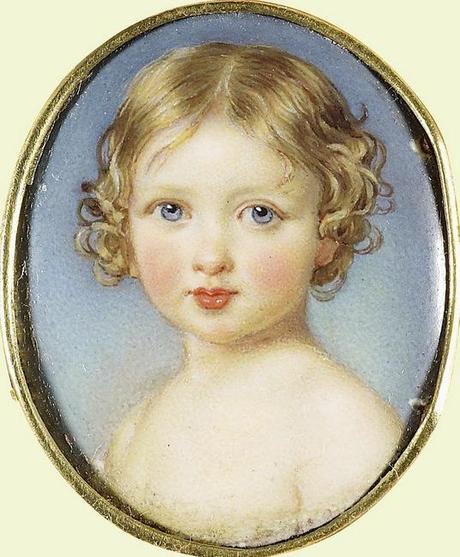

Princess Louise, Bell, c1850. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

When I was seven and going through the first of my extreme obsessions about the Victorians in general and Queen Victoria in particular, I decided that she must have REALLY liked children to have had so many. Now, as an adult, I know that actually she disliked children intensely and actually just REALLY liked having sex, regarding the resulting pregnancies as an unfortunate by-product of her enthusiastic couplings with poor old Prince Albert. Now THERE’S a mental image you’ll be cursing me for later on.

In her brilliant book, The Mystery of Princess Louise, Lucinda Hawksley explores the story of this most rebellious of princesses, who remains a fascinating enigma even now. Although Princess Louise is now regarded as perhaps the most charismatic and talented of Victoria’s offspring, she was regarded with something approaching marked disfavour by her exacting and easily irritated mother, although there was perhaps nothing very unusual about that. Probably Victoria just couldn’t get a handle on Louise’s creative, impetuous nature or, more likely, she thought her too much like herself – after all there was that supremely Hanoverian tendency to dislike one’s children, in particular one’s heir (and thus chief rival).

Princess Louise, Alice and Helena as bridesmaids at the wedding of Victoria, Princess Royal, January 1858. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

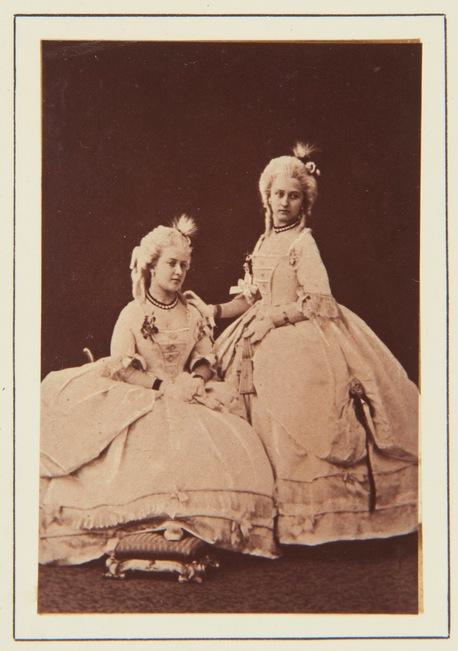

Princesses Louise and Helena in costume for a ball at Claremont in February 1865. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Luckily for Louise, Prince Albert was much more receptive to his daughter’s intelligence and creative abilities. You just have to look at the decline in royal involvement in the arts after his premature death in 1861 to see just how much of an intense interest Albert took in all forms of art and the important contribution he made not just to the royal collections but also to the royal family’s residences. A great reader and music lover, he was to make Princess Louise, with her early budding artistic talents and bright intelligence, a particular favorite and we can only imagine what sort of encouragement she would have received had he lived.

Unfortunately, he did not live and poor Louise, along with her other unmarried sisters, was forced to live in a sort of limbo at their side of their extravagantly mourning mother, putting aside their own youthful high spirits, ambitions and desires in order to meet the demands of their excessively needy mother. Louise, energetic, impatient and imaginative, found the gloomy isolation of Victoria’s lifestyle particularly irksome as she longed for more stimulating company and a more normal existence with all the balls, flirtations and fuss that her elder sisters had enjoyed before the veil of mourning dropped in December 1861.

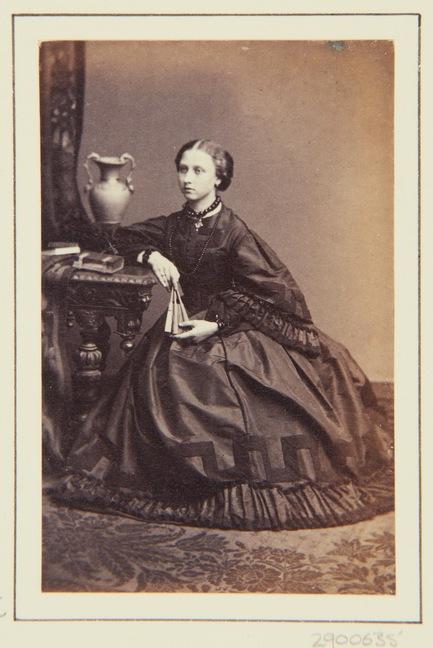

Princess Louise, Ghémar, October 1862. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Stifled, bored and frustrated, Louise no doubt feel even more trapped when she took up the position of her mother’s secretary in 1866, a post that was traditionally held by each eldest unmarried daughter with the baton being passed on to the next upon their marriage. To everyone’s surprise, Louise, whom her mother considered to be rather indiscreet, proved herself to be an excellent secretary and dealt with her mother’s vast correspondence with unexpected tact, something that drew them closer together.

Princess Louise, Hills and Saunders, c1868. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Although one senses that Victoria would happily have kept her daughters unmarried and beside her for the rest of her lives, echoing the unfortunately restricted daughters of her grandfather George III and Queen Charlotte, she forced herself to make an effort when it came to their marital concerns. In the case of Louise, who was enchantingly pretty as well as extremely well dressed and very witty, she had no shortage of suitors to work her way through, although, perhaps, inevitably none of them really came up to snuff. After the awkwardness and family rows caused by the rivalry between Denmark (the country of the Prince of Wales’ wife, Alix) and Prussia (the country of the Princess Royal’s husband, Fritz), Victoria decided to steer well clear of any princelings allied to either country as clearly they were a diplomatic stand off just waiting to happen. To the annoyance of her German relations, who had regarded Victoria’s daughters in a rather proprietal manner, she also showed a marked reluctance to marry Louise to one of their candidates either, wisely noticing that minor and most likely impoverished German princes weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms by the cynical British any more (if they ever had been), and instead, in a move that shocked everyone, gave her favour to a match closer to home with the handsome Marquess of Lorne, eldest son and heir of the Duke of Argyll.

Possibly Victoria’s romantic passion for Scotland and its history and people had much to do with her favour for such a match, which would be the first time that a daughter of a sovereign had been officially married to a subject since the marriage of Louise’s birthday twin, Princess Mary Tudor with Charles Brandon back in the sixteenth century. It was a historic moment and one that set a precedent for a tendency that we still see today – how those poor daughters of George III with their sad little secret romances must have wished that they had been accorded the same privilege.

The Wedding of Princess Louise and the Marquess of Lorne, Prior Hall, c1878. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Princess Louise’s wedding veil, which she designed herself. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Princess Louise on her wedding day, 21 March 1871. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Louise married the Marquess of Lorne in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle on the 21st of March 1871, wearing a Honiton veil that she had designed herself and a white silk gown with deep lace flounces. The ceremony was a marked contrast to that of her sister, Alice, which had taken place in July 1862, shortly after the death of Prince Albert and had been more like a funeral than a wedding, with the Queen turning up in full mourning and making no effort to look cheerful and the bride only being allowed to wear her wedding dress for the ceremony before having to change back into mourning immediately afterwards. Clearly the royal family had moved on from those dark days and even Victoria wore rubies with her mourning that day.

Although Louise’s marriage wasn’t always happy, she certainly seized upon the freedom that it afforded her – in Victorian times, married women were granted far more freedom within society than unmarried girls, particularly princesses, were allowed. In Louise’s case this meant finally being able to give proper expression to her passion for art, which had been tolerated rather than encouraged by her mother. Always far more liberally minded than her mother, she also took a great interest in the women’s rights movement and was a fervent supporter of suffrage. Like the young royals of today, Louise felt irked and restricted by her royal position but was not above using it if it suited her.

Princess Louise, Levitsky, August 1868. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Lucinda Hawksley writes at length about Louise’s artistic career and the quasi Bohemian lifestyle that this unconventional princess did her best to enjoy despite the restrictions that her royal position placed upon her. I found this absolutely fascinating to read about and came to the conclusion that she would have made a brilliantly amusing friend but a terrible and rather implacable enemy should one have the misfortune to cross her. There is also much discussion of the various rumours about romantic entanglements that occurred during Louise’s life, in particular the rumours that she had an illegitimate child before her marriage and her later relationship with the sculptor Boehm. Certainly it seems to me that Louise was a woman of enormous charm and an unconventional intelligence who never lost that rebellious streak that had disturbed her mother so much and this coupled with her not entirely satisfactory marriage makes it seem not entirely unlikely that she sought romance elsewhere. I actually hope that she did.

In 1878, Louise’s husband was appointed Governor General of Canada and the couple was duly despatched across the Atlantic to take up their position after an official inauguration in Halifax in November of that year. Before Louise’s arrival there were unhappy rumblings that she would be every bit as autocratic and difficult as her mother and would be too ‘royal’ for the distinctly liberal minded Canadians. Luckily, this turned out not to be the case and the couple’s residence in Canada was a triumph that served to strengthen the bonds between the Commonwealth country and its distant Queen and although Louise was to return to England in 1883, she was to continue to take an intense interest in Canada and its affairs for the rest of her long life.

Princess Louise, after Hills and Saunders, June 1869. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

Although Louise’s marriage had not been a great success, she and Lorne, now Duke of Argyll, grew closer in old age and she was devastated by his death in 1914. She herself would linger on for over two more decades before finally dying at Kensington Palace on the 3rd of December 1939 at the age of ninety one. She had long been in the habit from answering gentle ribbing from her siblings about her love of physical exercise with the sharp retort that ‘I’ll outlive you all’ and it turned out that she was right.

I really enjoyed Lucinda Hawksley’s book about this enigmatic and fascinating princess, which delivers both a brilliant and well considered insight into her complicated personality and also gives an intriguing perspective into Queen Victoria’s inner circle from the point of view of one of the most interesting of her children – both of which makes it a must read for anyone interested in the Victorian era.

Princess Louise, Downey, September 1870. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

******

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is now £2.02 from Amazon UK and $2.99 from Amazon US.

Blood Sisters, my novel of posh doom and iniquity during the French Revolution is just a fiver (offer is UK only sorry!) right now! Just use the clicky box on my blog sidebar to order your copy!

Follow me on Instagram.